Leading bone experts are championing a reclassification of osteoporosis to encompass more patients at risk for fractures. Such an expanded definition would raise awareness among patients, physicians, government agencies, and insurers.

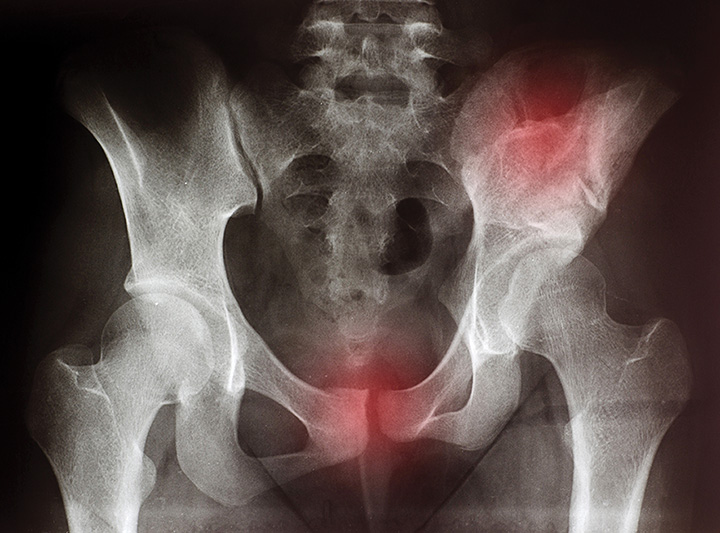

Most hip fractures occur in patients who do not have osteoporosis — at least according to the currently accepted definition of the condition. But that limited definition is leading to patients at risk for fracture being undertreated — and is a key reason the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group is proposing that the diagnosis of osteoporosis be expanded to include patients who clearly have an elevated fracture risk based on three additional criteria.

“Osteoporosis remains grossly misunderstood by most people, including perhaps some physicians, but certainly the public,” says Ethel S. Siris, MD, professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City and lead author of the working group’s position paper published last year in Osteoporosis International.

The position paper has been endorsed by the Endocrine Society and more than a dozen other professional organizations, including the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. It is expected to be incorporated into the next revision of the most important guideline on the condition — the National Osteoporosis Foundation’s Clinician’s Guide — in December.

Current vs. Proposed Criteria

In the U.S., the current criterion for the diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men over the age of 50 is a bone mineral density (BMD) test score that is 2.5 or more standard deviations less than that of the average healthy 30-year-old at the lumbar spine, femur neck, or total hip — that is, a T-score of minus 2.5 or lower. But BMD measures only bone quantity and not other important risk factors such as bone quality, so relying on this single measure alone misses a lot of patients who could be potentially helped by treatment, according to Siris.

Therefore, in addition to the T-score, the group proposes that physicians should consider an osteoporosis diagnosis in an older adult in three additional situations:

- Those who experience a hip fracture regardless of their bone mineral density T-score;

- Those with osteopenia by BMD who sustain a vertebral, proximal humeral, pelvic, or (in some cases) distal forearm fracture; and

- Those who have a 10-year risk based on the World Health Organization Fracture Risk Algorithm (FRAX) of 3% for hip fracture or 20% for a major fracture.

Resisting Bad News

Even when patients break a bone, both patients and physicians seem to resist the diagnosis of osteoporosis, according to working group member Nelson Watts, MD, director of Mercy Health Osteoporosis and Bone Health Services in Cincinnati and lead author of an Endocrine Society guideline on osteoporosis in men. This resistance is so great that only about 20% of Medicare-age women who sustain a fracture are evaluated for osteoporosis.

The working group hopes to raise awareness that treatment should be considered in these cases, Watts says, and several groups make up the target audience: patients, physicians, insurance companies, and government agencies.

Siris uses the example of a postmenopausal woman who presents with fractured hip and a T-score of minus 2.4 at the spine or the hip. Under the current definition, the diagnosis would be “osteopenia and hip fracture, which is crazy. The patient has osteoporosis and should be treated,” she says. “These are diagnostic criteria. We’re not saying everybody who meets the diagnosis needs drug X. We are saying, you have to be identified as having a disease that puts you at risk for future fractures, and something has to be done.”

The position statement has already been useful in getting the right treatment for patients, according to Joseph M. Lane, MD, professor of orthopedic surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City: “Some 55% of hip fractures occur in patients with osteopenia rather than osteoporosis; however, the insurance companies will not let you prescribe certain drugs unless the diagnosis of osteoporosis is made.” Lane has used the position paper’s expanded definition to convince insurance companies to pay for more appropriate treatment for these patients, for example, the anabolic bone-forming agent Forteo (teriparatide). The drug is more expensive but more effective for some patients than drugs such as bisphosphonates.

Have They Proved Their Case?

Of course, the proposal has its critics who say that the working group has not met the standard of proving that the benefits of expanding the definition outweigh potential harms. “Broadening the definition of a disease can have adverse consequences, including labeling a substantial proportion of the population with a problem that might not benefit from treatment and placing higher demands on the healthcare system to identify and treat the great number of patients meeting the expanded criteria. If treatments are not effective, healthcare resources are wasted and there is diversion of those resources away from other disorders for which treatment benefits are better established,” John T. Schousboe, MD, and Kristine E. Ensrud of the University of Minnesota write in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

These and other critics have questioned the evidence base for giving drugs to patients whose T-scores are better than 2.5. “Higher estimated fracture probabilities are not yet known to identify a subgroup of patients who benefit from treatment,” Schousboe and Ensrud write.

The proposal’s supporters respond that high fracture and re-fracture rates among patients with osteopenia demonstrate that osteoporosis is currently underdiagnosed and undermanaged and these patients warrant more attention. And although the clinical trials for the drugs currently used were designed to test their effectiveness primarily among patients with lower T-scores, there are many examples of evidence that some drugs can help in others as well.

Raising Awareness, Reducing Risks

Siris notes that the position paper makes no specific treatment recommendations but is aimed at diagnosis: “It is a way of raising awareness, making people understand that there are risks that you want to reduce.” In that example of a woman with a hip fracture and a BMD of -2.4, “you have to be thinking about a management strategy.” That strategy could start with a conversation focusing on what she calls “the big three”: adequacy of calcium and vitamin D to avoid a deficiency state; addressing the issue of fall risk reduction; and the potential benefit of a drug. Siris recommends looking at the literature to decide “which drug should you use for which patient and when should you not use a drug, to address, for example, whether a drug works in somebody whose high risk of fracture is based solely on FRAX.”

The criteria for diagnosing osteoporosis have changed over time as knowledge and treatment have changed, and supporters maintain that this is the next logical step. Like any change, it has critics, but with the backing of so many experts and organizations, this position paper is on a track to be incorporated into guidelines, and the supporters will be working to make it a part of ICD codes.

“We need a broader definition of osteoporosis, mainly to convince insurance companies that this is a patient worthy of receiving prescription drug therapy, but also to educate providers and patients that there is more to fracture risk than just bone density,” Watts concludes.

Seaborg is a freelance writer based in Charlottesville, Va. He wrote about estrogen therapy in the November issue.