Via an online video conference with Endocrine News, Mihail “Misha” Zilbermint, MD, discusses how the COVID-19 virus has changed the way he practices medicine in a hospital setting, and how his approach to treating patients may be changed forever.

One of the common terms that has been used to describe everything from the way we do our jobs to how we get our groceries during the advent of COVID-19 has been “the new normal.” Clinicians, nurses, techs, support staff, and others on the front lines of patient care have been vital in tamping down the spread of this new virus as well as treating those who have become infected.

Due to the “all hands on deck” nature in practices and hospitals across the country, many endocrinologists have found themselves face to face with treating the influx of new patients while also tending to their regular practices. As Mihail “Misha” Zilbermint, MD, shares his firsthand experiences, it’s clear that there are new methods of practicing medicine that may evolve from this worldwide healthcare crisis.

Zilbermint, the chief of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., established the Inpatient Diabetes Service at the hospital five years ago, which is comprised of a specialized multidisciplinary team trained to treat diabetes patients. In this capacity, he aides his colleagues in managing patients with diabetes who are in the hospital for a variety of health issues, from heart attack or stroke to major trauma surgery. “And of course, I do all other endocrine work as well,” he says, adding that complications with calcium levels, thyroid issues, and other endocrine-related conditions.

Telemedicine: Minimizing Risk

But as the virus has encroached upon his hospital, Zilbermint has had to adapt to treating patients in a new, safer way, namely telemedicine. However, the implementation has not been as smooth as he had hoped, at least on the inpatient side. “We are looking to give patients a tablet or an iPad so you can talk to the patient or maybe patient’s family members,” he explains. “The idea is that the nurses can check the patient’s vital signs, you can review the blood tests from home or remotely and you can figure out, for example, what dose of insulin can be given.”

“This outbreak will end at some point and as we look back, we are going to all see the importance of telemedicine and telehealth. And I am absolutely delighted by that. It should have happened a long time ago.”

But, Zilbermint says “we are not there yet. I’ve installed the software on my computer and I’m ready to go as soon as we are given the go-ahead, but we just aren’t there yet. We know that from an endocrinology standpoint, a lot of the inpatient diabetes management can be done remotely. But unfortunately, the inpatient billing process is not clear [telemedicine] and the practice may becomeless profitable.”

Zilbermint relates a story regarding a colleague at a local outpatient endocrinology office who has been practicing endocrinology for almost three decades and only recently implemented telemedicine. “She just started telemedicine two days ago and is trying to bill,” he says. “She’s worried that they are not billing correctly or if they’re going to get reimbursed. Even though they are scared about not being able to bill [for telemedicine appointments] they are going through with them because they need to see the patients, but they don’t want the patients in the office.”

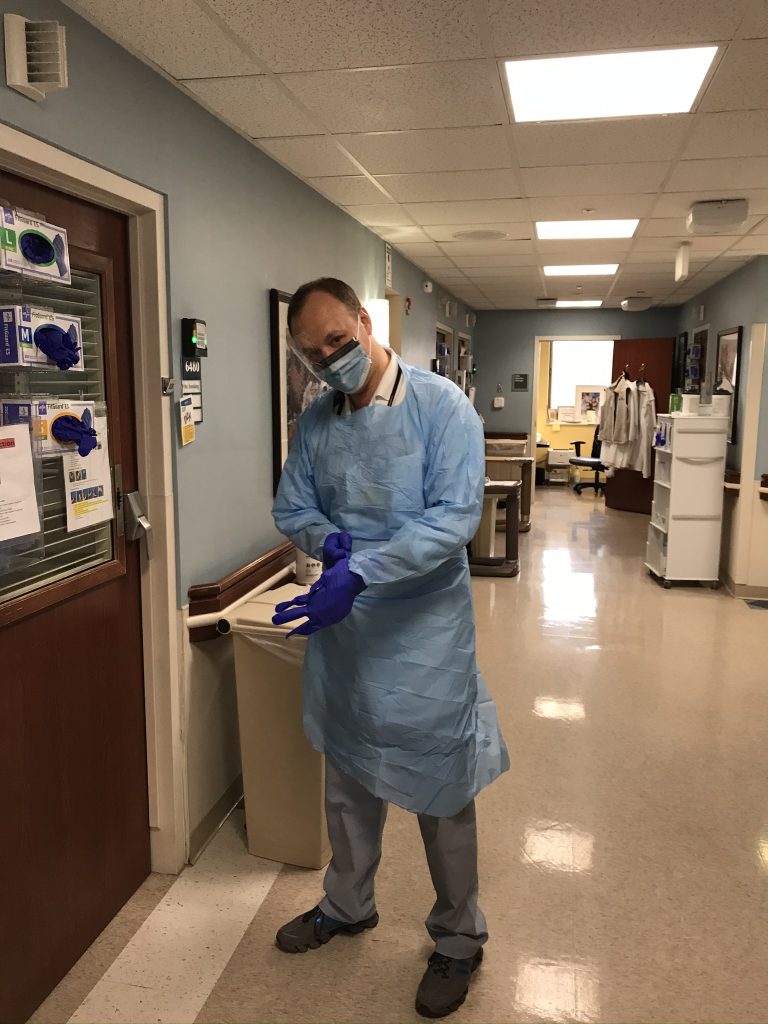

Zilbermint adds that one of the reasons he became an endocrinologist is being able to meet with a patient and look them in the eyes. “But in the modern reality, which is changing day to day, I find myself actually trying to spend as little time with the patients as possible,” he says. “Every extra minute you’re spending with the patient [in the hospital], you’re putting yourself at risk.”

Changing Roles During an Outbreak

Another one of the issues facing Zilbermint at Suburban Hospital is the need to devote time to the waves of patients coming in to be treated for COVID-19. In other words, donning his internist scrubs (more on that later) and helping out wherever he’s needed. In Italy, where the virus has hit particularly hard, Zilbermint has heard from his colleagues – endocrinologists who are also internists – who have been deployed to hospitals en masse.

“They don’t practice endocrinology any longer and have switched to internal medicine because it’s a war,” he says he was told, adding that thousands of final-year medical students were suddenly graduated in order to help out in the hospitals. “’Your medical school is over,’ they were told. ‘You are now a doctor.’”

According to Zilbermint, this happened the week of March 15 and added that if the “curve is not flattened [see box], there will be hundreds of patients coming in the next few weeks. I’m glad that I kept all of my credentialing and I’ve been working as a hospitalist a few times a year. I do a couple of hospitalist shifts in the emergency room to keep up with my skills. I even approached some of my ICU colleagues to ask them how to operate the ventilator.”

In epidemiology, the curve refers to the projected number of new cases over a period of time.

In contrast to a steep rise of coronavirus infections, a more gradual uptick of cases will see the same number of people get infected, but without overburdening the healthcare system at any one time.

The idea of flattening the curve is to stagger the number of new cases over a longer period, so that people have better access to care.

It explains why so many countries are implementing social-distancing guidelines, “shelter in place” orders, restrictive travel measures, and asking citizens to work or engage in schooling from home.

Source: CNBC

When Zilbermint spoke to Endocrine News via Zoom from his office at Suburban Hospital on March 20, he had not been deployed at that time but “the initial conversation happened with the hospitalist director about deploying the physicians who are also internists if we’re going to achieve what we see in Italy.”

Extra Precautions

Before he arrives at the hospital, Zilberment has implemented his own social distancing regarding his commute. Rather than take mass transit or even an Uber or a Lyft (to avoid fellow travelers as well as coughing drivers), he bikes the route to Suburban Hospital. As an associate investigator, he is also involved in research projects at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which, fortunately, is just across the street from the hospital, so he also spends a fair amount of time traversing Old Georgetown Road in Bethesda.

Once at work, his entire routine has changed lately: “My routine is I come to work, I immediately shower, I put my scrubs on and then before leaving work I just swore to my wife that I’ll shower for sure. So I shower again and then when I come home I shower again,” Zilbermint explains. “I try not to bring anything from work because it’s all high risk.”

Zilbermint even started wearing gloves while typing. “On my computer in my little office, I don’t use gloves because I clean everything,” he says. “But on those computer stations around the hospital, I essentially only use gloves because I don’t know who used this machine five minutes before me.”

The crisis has even seen a shortage of protective gear, according to Zilbermint: “As we expected, the amount of supplies on hand is fluctuating. We were asked to reuse the masks and we are doing so,” he says as he holds up his protective mask, his name clearly written across the bottom. “In the past it would be use it once and throw it away.”

Only the Beginning for New Technology

Despite the fears of patients and their families and even those of medical caregivers on the front lines dealing with this virus, Zilbermint believes that in the long term, the way care is delivered in the future is going to change drastically. “Telemedicine is going to win and it’s going to grow, and we are going to develop and incorporate it into our daily lives,” Zilbermint says.

“As we expected, the amount of supplies on hand is fluctuating. We were asked to reuse the masks and we are doing so. In the past it would be use it once and throw it away.”

He adds that because of what clinicians and patients and their families have had to deal with regarding receiving treatment and care during the COVID-19 outbreak, there will be a new appreciation for telehealth and the benefits it provides. These benefits have been reported on in the pages of Endocrine News in the past (“Long Distance Relationship,” September 2015) and have been long known by healthcare practitioners, both as a means to communicate with each other as well as noninvasive method to see and treat patients. Unfortunately, as with any new technology, it’s often difficult to get some patients to adopt and use something new and unfamiliar.

“This outbreak will end at some point and as we look back, we are going to all see the importance of telemedicine and telehealth. And I am absolutely delighted by that,” Zilbermint says. “It should have happened a long time ago.”