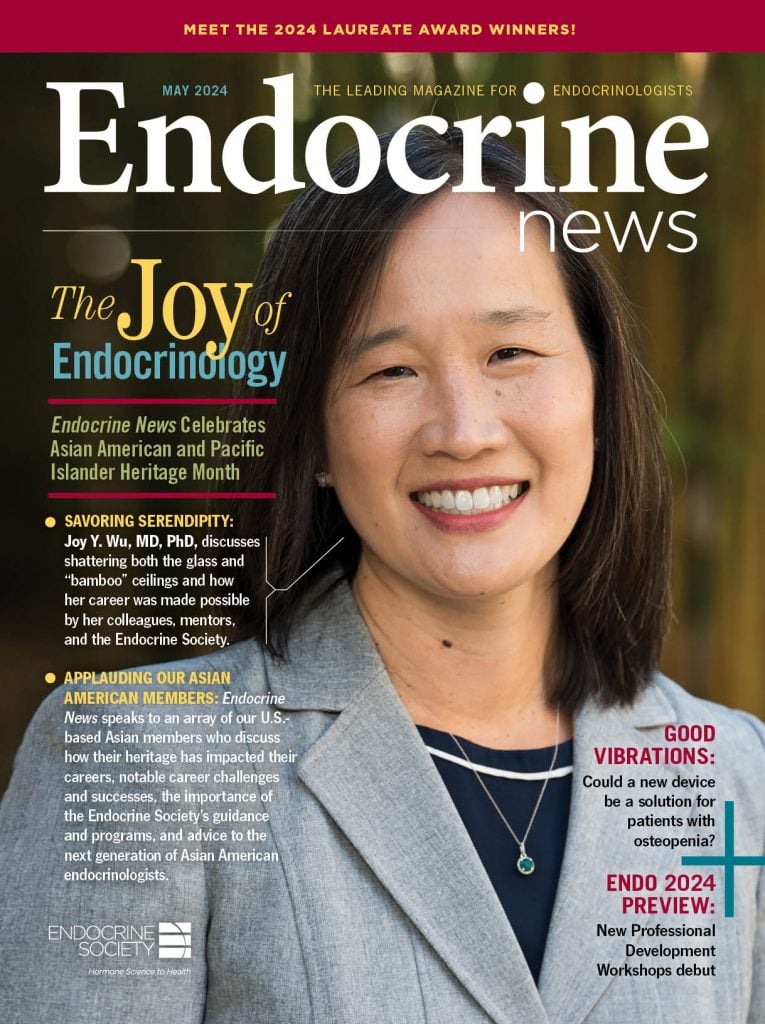

As Endocrine News celebrates Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we talk to Joy Y. Wu, MD, PhD, chief of the Division of Endocrinology at Stanford University about her personal and professional journey through the field of endocrinology as well as how her career path has been shaped by her mentors, colleagues, and especially the Endocrine Society.

In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, Endocrine News spoke to Joy Y. Wu, MD, PhD about her illustrious career and how she got to where she is now: Chief of the Division of Endocrinology at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. May also happens to be National Osteoporosis Month, and bone health is Wu’s chosen area of focus.

As of 2023, Asian Americans represent about 6% of the overall U.S. population and are the fastest-growing segment, with numbers expected to continue increasing over the next few decades. However, this population faces certain barriers to advancement that Wu hopes to see eradicated. “Within medicine, we’re not considered underrepresented because, at the medical student and early-career stages, Asian-Americans are the second largest group after Whites. There are many important efforts to recruit those who are underrepresented in medicine and support them in education and their careers,” she says. “But it’s also clear that, as you go up the leadership ranks, it’s reminiscent of the same trends that we see for women in medicine: women are very well represented among medical students and at the early-career stages, but — in what is often referred to as the ‘leaky pipeline’ — as we look at higher levels such as department chair or dean, there are fewer and fewer women, and that same trend seems to apply for Asians. There is still work to be done.”

Wu herself has found her way through this double “glass/bamboo ceiling,” as her career trajectory attests. In describing her path, Wu reveals three key themes: finding a niche that both satisfies extensive clinical need as well as offers opportunities for fascinating research, excellent mentorship, and the Endocrine Society.

Clinical and Research Foci

“Clinically, my interest focuses on osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease. It’s an area I’ve been interested in since my fellowship training,” Wu explains, “and it’s an area of great public health concern.” Osteoporosis affects 10 million people in the United States, with another 44 million at risk, according to an Endocrine Society patient resource, with 1.5 million experiencing potentially devastating fractures every year.

As Wu has taken on administrative duties at Stanford, she has narrowed her clinical focus to optimizing bone health in patients undergoing cancer treatment, which can impair bone health for multiple reasons, including inducing premature menopause among others. Explains Wu: “Patients with breast cancer are often treated with endocrine therapies that effectively prevent recurrence but then, of course, cause bone loss because the actions of estrogen are inhibited.” In the Joy Wu Lab, meanwhile, her research includes both basic and translational research, encompassing how to make bone-forming osteoblasts and understanding how the anabolic medications for osteoporosis like teriparatide work.

“As you go up the leadership ranks, it’s reminiscent of the same trends that we see for women in medicine: women are very well represented among medical students and at the early-career stages, but — in what is often referred to as the ‘leaky pipeline’ — as we look at higher levels such as department chair or dean, there are fewer and fewer women, and that same trend seems to apply for Asians. There is still work to be done.” — Joy Y. Wu, MD, PhD, Chief, Division of Endocrinology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Making more and better-functioning osteoblasts, she explains, is critical if a cure for osteoporosis is ever going to be found. “We’ll have to find a way to build bone safely and then maintain the new bone that is made,” she says. “Currently, most of the prescriptions for osteoporosis medications target the other side of the process, which is bone resorption.” Her team has been working on inducing pluripotent stem cells to become osteoblasts and reprogramming skin fibroblasts into osteoblasts.

A related area of exploration at the Wu Lab is the bone marrow microenvironment: How it supports hematopoietic cells and why and how cancer cells also thrive there. Breast cancer in particular most commonly metastasizes to bone. “The cells that become osteoblasts secrete growth factors and cytokines and express molecules on their surface that are important for supporting normal hematopoietic stem cells,” Wu says. “The cancer cells that come into the bone marrow environment may hijack some of these signals, taking advantage of some of the factors that are already produced, which provide a supportive environment for cancer cells to engraft and expand. So, we want to better understand that process and find ways to disrupt it.” In mouse trials, the team is investigating whether the anabolic medications used for osteoporosis might be safe and effective in people with cancer, a potentially revolutionizing approach.

Importance of Mentorship

Wu did not always know that bone health would be the subject of her life’s work, however. “When I was an MD/PhD student in [Society] past-president Anthony (“Tony”) R. Means’ lab at Duke University School of Medicine studying male germ cell development, he encouraged me to attend the Endocrine Society meeting, which was in New Orleans that year. I was looking for a specialty where I could meld my clinical and research interests,” Wu says. This was Wu’s first fork in the road.

Another very significant mentor and past-president in Wu’s career is Henry M. “Hank” Kronenberg. After her graduate school and medical school training, she did her residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and then matched into Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) for her clinical and research fellowship in endocrinology. “When I started, I thought I might study diabetes because that’s the largest disease focus within endocrinology and a critically important disease that affects so many people with so many health implications,” she explains. “But, during my clinical years, I met with Kronenberg, who was doing research on bone and osteoblasts, and he shared a recent paper showing that osteoblasts could influence hematopoietic stem cells published by one of the endocrinology fellows, and I thought that was so interesting.”

“Whether I was good at picking mentors or got lucky or a little bit of both, I think having great mentors was so critically important in that they not only trained me in rigorous science but also really advocated for me — they’re still advocating for me even decades later. They are still very much a part of my life.” — Joy Y. Wu, MD, PhD, Chief, Division of Endocrinology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Although studying bone had not been something she had thus far considered, she says the more she talked with Kronenberg and the more she learned about the research in his lab, the more fascinated she became. About halfway through her clinical year, she decided to pivot and focus on metabolic bone disease and osteoporosis. “For me, that has been a wonderful decision,” Wu says. “There’s so much opportunity for interesting research, and it’s an area of great clinical need. I have also had a lot of great opportunities because I somewhat serendipitously decided to focus on an area of endocrinology that’s rather specialized.”

Although Wu invokes serendipity, she played a deliberate role in choosing the right guidance along her path. “I’ve always been very well supported, and perhaps one thing I did really well was picking my mentors, especially [Means] as my PhD mentor and [Kronenberg] as my postdoc mentor. Whether I was good at picking mentors or got lucky or a little bit of both, I think having great mentors was so critically important in that they not only trained me in rigorous science but also really advocated for me — they’re still advocating for me even decades later. They are still very much a part of my life.”

Endocrine Society’s Impact

Means, as Wu explained, nudged her to attend her first Endocrine Society meeting, and from there everything fell into place. “The Endocrine Society is the reason I became an endocrinologist,” Wu says. “When I attended the meeting in New Orleans, I was amazed by the fact that there were clinical endocrinologists, basic scientists, and clinical investigators all together, and it seemed like a really interesting and supportive field. I literally decided that weekend to become an endocrinologist, so the Endocrine Society has always had a special place in my heart.”

Wu has also been very involved in committees and governance within the Society. When Means was president-elect, he appointed her to what is now called the Training and Career Development Core Committee, where she served for a few years before becoming a co-chair. As part of that experience, she had the opportunity to sit in on what was called Council, where she learned how Society governance works. Over time, she explains, she got involved with other committees such as the Publication Core Committee as well as participated in some of the strategic planning task forces. “Then, in 2019, I was elected to what is now called the Board of Directors and had the opportunity to serve for three years,” Wu says. “That was a very gratifying privilege. It’s really amazing what this Society does around the world to promote endocrinology, not just clinically, but also in terms of research, advocacy, and education.”

Looking Back

Wu’s career has advanced her understanding of more than just her clinical and research interests. She has seen how barriers — some insidious, some explicit — have affected women in medicine and science, for example: “When I started out, I saw that there were so many women in endocrinology, and, at the time, I remember having a conversation with one of my co-fellows about why we were still talking about women in endocrinology — it’s all fixed, right? Only after I became faculty and started on my own career path did I become more aware that there are still barriers to advancement.”

With the number of female medical students well above 40% for the last few decades, plenty enter the so-called pipeline. But, looking at the advancement from assistant to associate to full professor, the falloff in women is significant. “Over the years, I’ve become aware that there are many reasons for this,” Wu says. “They don’t have to be individually large reasons, but they can cumulatively still have a pretty significant effect. Overall, women are offered fewer opportunities, such as invitations to give seminars and nominations for awards and that kind of thing. There are always multifactorial reasons, but, when you look across the board, the advancement of women is still not what it could be to achieve gender parity.”

Another challenge for women in our society is, of course, balancing career and family needs. Wu says she was fortunate that her husband Sean Wu, MD, PhD, a physician-scientist and cardiologist, was not only supportive of her career but also played an equal role in taking care of their children. “But, for a lot of people, when it comes down to trying to balance a family’s needs against work, it can be harder for women to advance, again speaking on a collective scale,” she says. “Those are challenges that we still have to face, but I’ve been fortunate to have both family support, not only from my husband but also both our sets of parents, and mentors that have gotten me through, and I feel very grateful for that.”

Barriers notwithstanding, Wu firmly believes that endocrinology is a wonderful field for women. “It’s very supportive,” she says, “and the Endocrine Society has been phenomenal for modeling how women can thrive in leadership.” That modeling was especially transformative for Wu, who did not formerly see herself becoming a leader in the way she has. “I’m still an introvert at heart, but my younger self was painfully shy and would have been surprised at becoming a division chief because that is so public.”

When the idea was first suggested to her, in fact, she laughed. Since then, she has grown into the leadership role and again credits her mentors for helping her along the way. In addition to Means and Kronenberg, her earlier mentors, she appreciates that her former division chief at Stanford, Fredric Kraemer, and former department chair, Robert Harrington, offered her leadership opportunities. “Thanks to both leadership training and having people who believed in me and supported me, I became comfortable with the idea that I could take on leadership positions. I had this idea that we tend to view leaders as people who are outspoken, and I thought, there’s no way that I can do that,” Wu says. “But [Kraemer and Harrington] showed me that I can be persuasive when it’s something I believe in, and I think that is consistent with a lot of findings on women in leadership. Women are very good at advocating, especially for other people or for causes that they believe in.”

Looking Forward

In the short term, Wu is looking forward to ENDO 2024, “I love ENDO, where I get to hear about the latest exciting advances in endocrinology on the clinical and research fronts, but also, just as importantly, it’s where I get to catch up with my friends and colleagues from around the world.”

A special perk for Wu this year is that ENDO 2024 will take place in Boston, where she lived for 11 years, first during her clinical training at MGH and then as faculty there. “I have the honor of being one of the presenters in the Endocrine Society and American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Joint Presidential Session: ‘Clonal Hematopoiesis, Skeletal Cells and Metabolism,’ where I’ll be speaking about our research on interactions between bone and blood in health and disease,” she says.

Wu is the first woman division chief of endocrinology at Stanford as well as the first Asian. Interestingly, her appointment in 2022 started on May 1st, the beginning of AAPI awareness month, which brings this story full circle. “That was special,” she says, “breaking through sort of a double glass and bamboo ceiling.”

Horvath is a Baltimore, Md.-based freelance writer. In the April issue, she wrote about the ENDO 2024 session, “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Reproductive Endocrinology.”