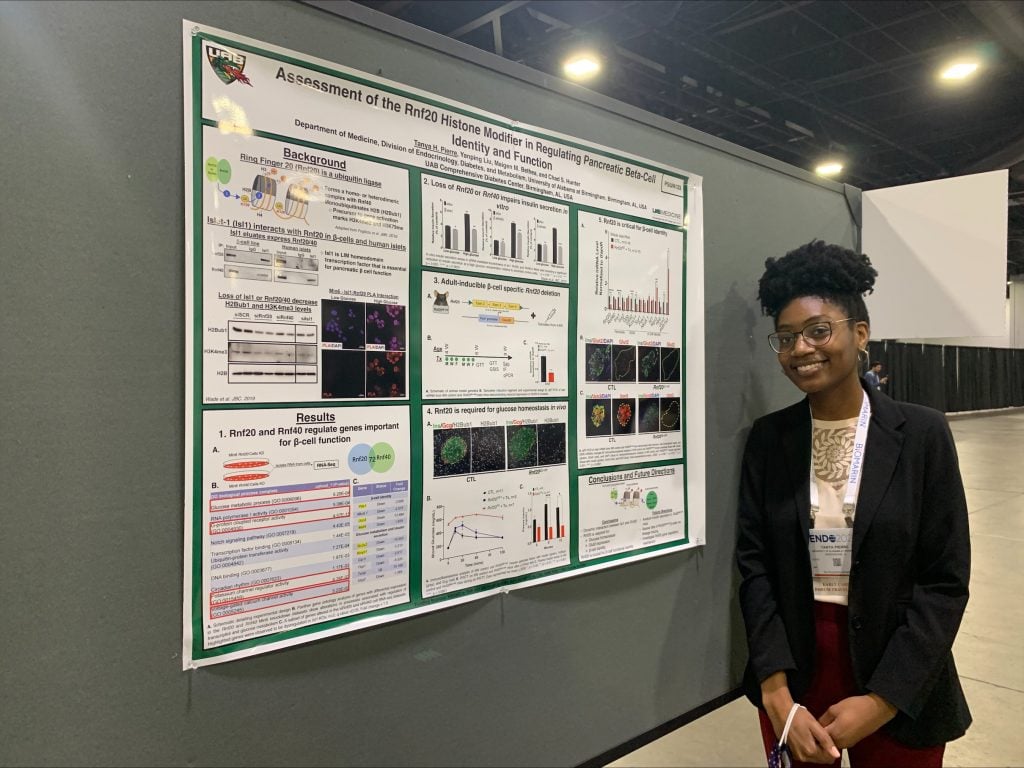

Fourth-year graduate student Tanya Pierre at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Comprehensive Diabetes Center talks to Endocrine News about when she realized that she could “do science” as a career, how she hopes her research will help her community, and the importance of awards to help young researchers continue their work.

For many young researchers, working to unlock the mysteries of diseases is coupled with balancing the financial burdens of educational and laboratory expenses. But for Tanya Pierre, a fourth-year graduate student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), the balancing was recently made tremendously easier. Pierre is a recipient of the Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Individual National Research Service Award (F31) — a reward that honors young scientists’ hard work and promising futures.

The Kirschstein-NRSA program’s purpose is to “enable promising students with potential to develop into productive, independent research scientists and to obtain mentored research training while conducting dissertation research,” according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The award will support up to three years of Pierre’s completion of her PhD and her research project entitled, “Elucidating the role of the Rnf20 Histone Modifier in Pancreatic Beta Cell Function and Senescence.”

Pierre earned her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Ga., and after graduation, she knew research was her future. Her search for postbaccalaureate programs led to a position at the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center in the lab of Chad Hunter, PhD, where she’s worked the past five years.

Endocrine News spoke with Pierre to learn more about her NIH-funded project and what life advice helps her reach her goals.

Endocrine News: When did you know you wanted to pursue a career in science and research?

Pierre: I wasn’t aware research was a career opportunity for me until my first year of college at Agnes Scott. I think the first thing we did in our biology class was learn about different careers in sciences, so that’s when I thought I could actually do science as a career. We had an office at school that helped students find summer research so I talked to the director there, Dr. Molly Embree, and she helped me figure out where I could go over the summer to explore research more. I was able to do some summer research programs and that allowed me to further fall in love with research and realize that’s what I wanted to do.

EN: And when did your focus become diabetes research?

Pierre: I knew I wanted to do research where I could make an impact on something that affects members of my [African American] community. And then, fortunately, the first research program that I was able to participate in was in a lab studying type 1 diabetes and its connection to environmental toxins. So, after that project, I knew that diabetes was really interesting. I did try to get into other areas, but every other research program I went to, I always ended up in a diabetes lab, so I feel it was meant to be.

EN: The F31 award includes stipends, living expenses, contributions to the cost of tuition and fees, as well as your research supplies, books, and scientific meetings. That’s phenomenal support to help you complete your PhD and research. Can you share the details of your funded project?

Pierre: My current project is focused on a transcriptional coregulator, called Rnf20, and trying to figure out how it impacts pancreatic beta cell development, function, and maintenance. So, right now I’m currently profiling an adult knockout of Rnf20 that’s enriched within the beta cells to see what happens. Thus far, we have observed some impairments of glucose homeostasis and markers of the onset of senescence that I hope to further elucidate in this project.

EN: And how will your work hopefully impact the lives of diabetes patients?

Pierre: One of the current therapeutic approaches that is being tested is islet replacement therapy and while it would be ideal to transplant donor islets, that number is limited. So, another approach is developing islets using embryonic stem cells. And while that has been successful at generating “beta-like” cells, they fail to fully replicate the islets that we already have naturally. Our work is aimed at increasing knowledge about the factors that are needed for beta cell identity and function. In order for them [beta-cells developed from stem cells] to properly maintain glucose homeostasis, you have to have a better idea of what those things [transcription factors and co-regulators] are so we can develop the best beta cells or islets to allow for sustained glucose homeostasis in patients with diabetes.

“The first research program that I was able to participate in was in a lab studying type 1 diabetes and its connection to environmental toxins. So, after that project, I knew that diabetes was really interesting. I did try to get into other areas, but every other research program I went to, I always ended up in a diabetes lab, so I feel it was meant to be.”

Tanya Pierre, graduate student, Comprehensive Diabetes Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Ala.

EN: What do you like most about the lab environment? How do you and your fellow lab mates stay on task and motivated?

Pierre: I think there’s a nice balance in our lab where everyone’s willing to help each other figure things out or troubleshoot, if needed. But we also frequently have group outings to do things outside of science that allow us to further connect without focusing on stuff that may be stressing us out throughout the week. Recently we went to an escape room, and that allowed us to use our brains in another way than we usually do.

EN: Escape rooms are fun! Last question: has there been some advice that a mentor or past teacher has passed down to you that keeps you going in this specialty?

Pierre: The one thing that I continuously repeat to myself that I’ve been told is that ‘everything that’s meant for me, will never miss me.’ Sometimes experiments don’t work, and I just think, ‘maybe it wasn’t the right time,’ or if I’m waiting to see if I get a grant, I think ‘if it’s meant for me, I will get it.’ If the result is supposed to happen, it will happen. The data is the data, you can’t force it.

—Shaw is a freelance writer based in Carmel, Ind. She’s a regular contributor to Endocrine News and writes the monthly Laboratory Notes column.