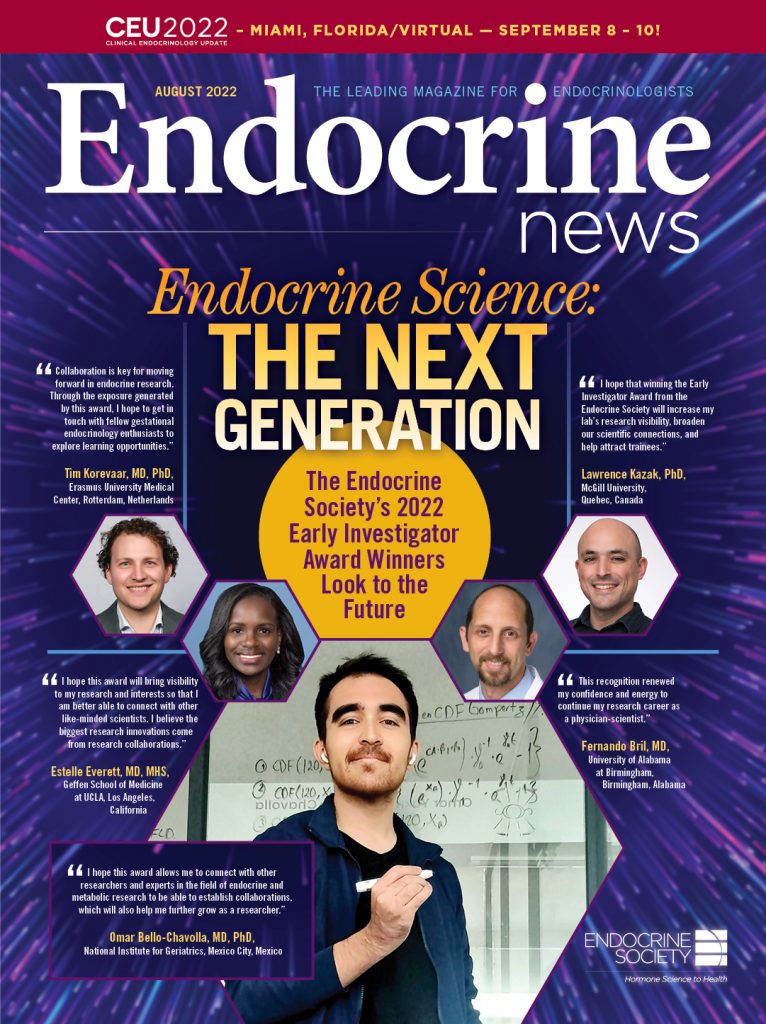

Every year the Endocrine Society recognizes endocrinologists who are in the early stages of their research careers with the Early Investigator Awards. Endocrine News spoke to the five researchers from around the world to find out more about their award-winning research, the award’s potential impact, as well as the biggest challenges facing them today.

While their backgrounds and locales may differ broadly, the winners of this year’s Endocrine Society Early Investigators Awards have one common thread of making significant contributions to endocrine-related research in the blossoming stages of their careers.

These five young researchers have persevered through the challenges of starting a new laboratory, balancing clinical obligations, and finding mentorships and funding opportunities to be recognized for their accomplishments and honored with an award established to assist in their research goals.

The 2022 winners are: Fernando Bril, MD, who is completing hisfirst year fellowship of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; Estelle Everett, MD, MHS, an assistant professor at the Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Lawrence Kazak, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry at McGill University, Quebec, Canada; Tim Korevaar, MD, PhD, in his first year of academic fellowship in endocrinology at Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands; and Omar Bello-Chavolla, MD, PhD, is in his second year as an associate professor at the National Institute for Geriatrics in Mexico City, Mexico.

Endocrine News spoke with each of them to learn more about what the award means for their work.

What or who inspired you to apply for the award?

Everett: Since becoming a member of the Endocrine Society, I have found the Society to be very supportive of its early-career members so I thought it would be a good idea to apply since I am in the early stages of my research career.

Korevaar:The concept of standing on the shoulders of giants inspired me to apply for this award. I am inspired by the previous winners and endocrinology staff at the Erasmus University Medical Center.

Kazak: In academia, there are few objective markers of success. Simply applying for an award is beneficial because it forces you to reflect upon your career progress and research program. It creates the opportunity for receiving feedback from your peers and gives you the chance to determine how you are perceived in your field.

“Collaboration is key for moving forward in endocrine research. Through the exposure generated by this award I hope to get in touch with fellow gestational endocrinology enthusiasts to explore symbiosis and learning opportunities.”

Tim Korevaar, MD, PhD, first-year fellow, endocrinology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Bello-Chavolla: I have been working on endocrine-related research since 2016 when I started my PhD work and have been aware of this recognition by the Endocrine Society ever since. I was fortunate to be able to contribute to endocrine and metabolic research in Mexico during that time and saw many very promising scientists be recognized for their accomplishments. I got notified of the call for awards earlier this year and decided to give it a try, considering it would be a great step forward for my career.

Can you explain your research in a few sentences?

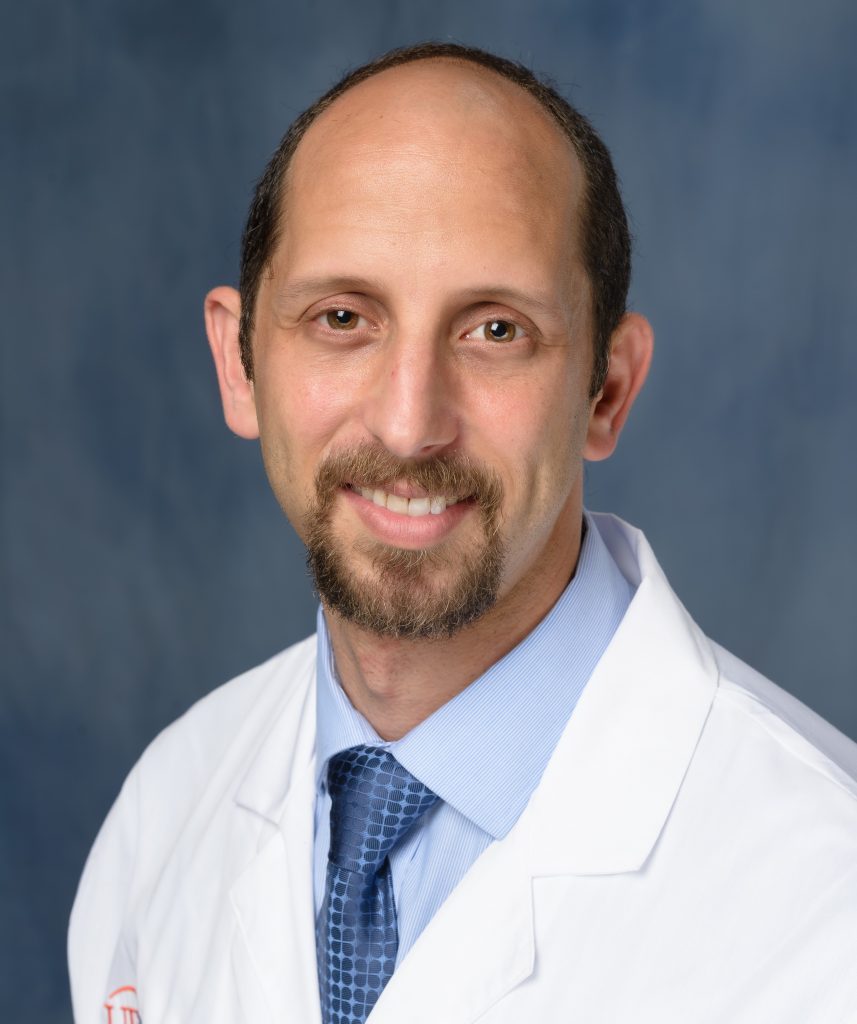

Bril: As a consequence of the obesity epidemic, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the most common chronic liver disease worldwide. Endocrinologists and primary care providers managing patients with type 2 diabetes are at center stage, as approximately two-thirds of patients with type 2 diabetes have NAFLD. In addition, patients with type 2 diabetes tend to progress faster to more severe forms of liver disease, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and NAFLD-related cirrhosis.

My main research interest has been to understand the metabolic mechanisms that promote the progression of NAFLD in obesity and diabetes, identify markers for early diagnosis, and assess pharmacological approaches that may be able to change the natural history of the disease. Unfortunately, despite its exponential growth in the last few decades, our understanding of NAFLD remains largely incomplete. Using state-of-the-art techniques, such as euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamps with the use of stable isotopes to measure different metabolic pathways (glucose turnover, de novo lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and/or lipolysis rates), liver and cardiac magnetic resonance 1H-spectroscopy and elastography, and targeted/untargeted metabolomics, we have tried to try to fill some of the current knowledge gaps.

“I found that it is critical to develop a support system of peer and more senior mentorship, from your own institution as well as outside one’s institution in order to get the perspectives and guidance needed to be successful. The Endocrine Society has been tremendously helpful in this regard, especially through programs like Future Leaders Advancing Research in Endocrinology (FLARE).”

Estelle Everett, MD, MHS, assistant professor, Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, California

Everett: My research involves exploring and addressing barriers to care in vulnerable populations with type 1 diabetes. I have a particular interest in addressing inequities in access and use of diabetes technology. I recently received a K23 award from the NIH/NIDDK to evaluate the use of hybrid closed-loop insulin pumps in those with type 1 diabetes and an A1c greater than 9% in both an academic and safety net setting and evaluate barriers and facilitators of optimal use.

Korevaar: I perform epidemiological studies on the physiology of maternal endocrinology during pregnancy, predominantly thyroid (dys)function during pregnancy and how this affects the risk of adverse pregnancy and child outcomes. I have a special interest in fetal brain development and thyroidal hCG stimulation, but am also interested in fertility, endocrine disruption, iodine availability, and levothyroxine (over)treatment. An important research line is our Consortium on Thyroid and Pregnancy, a collaboration of more than 25 prospective gestational thyroid studies in which we meta-analyze individual participant data to investigate risk patterns, high-risk subgroups, and levothyroxine treatment effects.

“In academia, there are few objective markers of success. Simply applying for an award is beneficial because it forces you to reflect upon your career progress and research program. It creates the opportunity for receiving feedback from your peers and gives you the chance to determine how you are perceived in your field.”

Lawrence Kazak, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Biochemistry, McGill University, Quebec, Canada

Kazak: My lab focuses on thermogenic adipocytes as a model system to study how cells use energy. We take an interdisciplinary approach by using methods in molecular biology, biochemistry, bioenergetics, and mouse physiology. A central objective of my lab is to define the various metabolic pathways that promote energy dissipation in brown adipocytes.

Bello-Chavolla: I focus on statistical modelling and machine learning with epidemiological and clinical data to unravel particularities of metabolic diseases in admixed populations, with a focus on Mexican and Latin American populations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, our work focused on characterizing the uniquely increased risk for severe COVID-19 attributable to the epidemic of cardio-metabolic diseases in Mexicans and the metabolic adaptations to severe SARS-CoV-2 infections that contribute to increased risk of severe disease and mortality independent of chronological age. My more recent work also has been focusing in developing and applying a framework to systematize data-driven diabetes subtype classification using readily available clinical measurements to characterize diabetes and pre-diabetes heterogeneity in Mexico, the U.S., and Latin American populations.

What’s the biggest challenge facing scientists who are in the early stages of their careers today?

Bril: As an early-stage physician-scientist, I believe one of the most significant challenges we face is the increasing clinical load and pressure to maximize the number of clinics per week and the number of patients we see per clinic. Increasing clinical workload makes it very difficult to devote time to write and focus on research.

Everett: Navigating a research world. This can be especially challenging for physician-scientists who are balancing clinical responsibilities, teaching, and leadership roles, as well as trying to develop themselves as a researcher. I found that it is critical to develop a support system of peer and more senior mentorship, from your own institution as well as outside one’s institution in order to get the perspectives and guidance needed to be successful. The Endocrine Society has been tremendously helpful in this regard, especially through programs like Future Leaders Advancing Research in Endocrinology (FLARE).

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, our work focused on characterizing the uniquely increased risk for severe COVID-19 attributable to the epidemic of cardio-metabolic diseases in Mexicans and the metabolic adaptations to severe SARS-CoV-2 infections that contribute to increased risk of severe disease and mortality independent of chronological age.”

Omar Bello-Chavolla, MD, PhD, associate professor, National Institute for Geriatrics, Mexico City, Mexico

Korevaar: Forming a network of stimulating mentors around you who see you as their peer.

Kazak: Most early-career scientists are challenged by navigating how to hit the ground running with scientific progress. When you open your lab, it is typically empty. You have to think about the equipment you will need, get that equipment into the lab, and learn to use it. At the same time, you need to learn to screen/evaluate trainees. Once the lab is equipped and staffed, you need to train your personnel. You need to learn to be a mentor, which requires drastically different approaches for each lab member. All the while, you need to make the decisions on research directions, stay abreast of the literature, write grants, and go to scientific meetings. Problems at any one of these stages, can severely hamper research progress. With experience, hopefully you can master these different roles.

Bello-Chavolla: A main determinant of this is where in the world you are working as an early-career scientist. In Mexico, as in many parts of the world, we as early-career scientists routinely face age-related discrimination that hinders our eligibility for tenure promotion, grant acquisition, and access to students for mentoring. This puts us in a competitive disadvantage with more experienced researchers, who often get preference for many of these career-furthering opportunities. However, one of the biggest and most urgent problems we face as early-career researchers in Mexico and many developing countries is access to funding to engage in more challenging and complicated research questions, with many of us having to fund our research and publications with our own salaries. I believe the research community in Mexico should consider the vitality of supporting the growth and development of early-career researchers to further their academic and professional developments, as the Endocrine Society promotes with this and other awards.

How do you hope winning the Early Investigator award will help support your goals as an endocrine scientist?

Bril: One of the most important things that I learned from Dr. Cusi, one of my mentors, is that the key to success in research is resilience (some credit goes to my mom here as well!). Research constitutively involves getting rejections, such as with manuscripts, grants, and proposals. It is very easy to get discouraged, especially at early stages. This award was a strong reinforcement that I must have done, at least some things, right. This recognition renewed my confidence and energy to continue my research career as a physician-scientist.

Everett: I hope this award will bring visibility to my research and interests so that I am better able to connect with other like-minded scientists with similar interests. I believe the biggest research innovations come from research collaborations.

Korevaar: Collaboration is key for moving forward in endocrine research. Through the exposure generated by this award I hope to get in touch with fellow gestational endocrinology enthusiasts to explore symbiosis and learning opportunities.

“As an early-stage physician-scientist, I believe one of the most significant challenges we face is the increasing clinical load and pressure to maximize the number of clinics per week and the number of patients we see per clinic. Increasing clinical workload makes it very difficult to devote time to write and focus on research.”

Fernando Bril, MD,first-year fellow, endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama

Kazak: Receiving any award can certainly boost confidence. I hope that winning the Early Investigator Award from the Endocrine Society will increase my lab’s research visibility, broaden our scientific connections, and help attract trainees.

Bello-Chavolla: One of the most significant challenges I encountered early in my career as an independent scientist was how to promote my work and give visibility to the many projects we were engaging in. I believe this award will allow our work to reach many more scientists and hopefully help inspire other early-career investigators to apply for this award and in-training researchers to continue generating invaluable research independent of the many difficulties we may encounter in our careers. Finally, I hope this award allows me to connect with other researchers and experts in the field of endocrine and metabolic research to be able to establish collaborations, which will also help me further grow as a researcher.

—Fauntleroy Shaw is freelance writer based in Carmel, Ind. She authors the monthly Lab Notes for Endocrine News.