Fresh from receiving his 2020 Laureate Award for Outstanding Innovation, Christopher B. Newgard, PhD, discusses how collaboration has shaped his research and why he focuses on metabolomics to unlock the mysteries of cardiometabolic diseases.

Christopher B. Newgard, PhD, does not hesitate to give credit to the many mentors and colleagues who have inspired his devotion to metabolic research. As director of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute and Sarah Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center, and professor in the departments of Medicine and Pharmacology & Cancer Biology at Duke University School of Medicine, he leads one of the most active metabolomics laboratories that seeks to better understand pandemic metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes.

This year, Newgard is the recipient of the Endocrine Society’s 2020 Laureate Award for Outstanding Innovation — a recognition of demonstrated innovation and entrepreneurship to further endocrine research or practice in support of the field of endocrinology, patients, and society at large.

Endocrine News spoke with Newgard to learn more about what motivated his discoveries.

Endocrine News: What has winning the Laureate Award meant to you?

Christopher Newgard: It’s humbling. I am particularly happy to be recognized for innovation. I think all scientists want to be viewed as innovative in what they do. So that’s certainly quite pleasing. And, of course, it’s fine for me to receive the recognition as a longtime leader of a group but none of it would be possible without a lot of contributions from a lot of people. I’m honored and looking forward to representing a whole group of people who have helped along the way.

EN: How did metabolomics become your field of interest?

CN: I’ve been an independent investigator since I started at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in 1987 and I’ve had fantastic mentorship. A huge reason why I’m pushing boundaries in metabolic research is that I’ve had just absolutely fantastic mentors in metabolism. Perhaps most prominently was the late Denis McGarry, who was British and knew metabolism backwards and forwards. He drilled it into me and that was a great a start. Roger Unger was another mentor at UT Southwestern. So, it starts with them and shapes an approach to science.

I study metabolic regulatory mechanisms and how those go wrong in cardio-metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which has included embrace of newer technologies and innovations. It started at UT Southwestern when a colleague, Dean Sherry, who was a professor at the medical school, came to me and said ‘I’d like to come to your lab and do a sabbatical because I know your research about metabolism as it relates to diabetes and I think I could bring some really exciting tools to the party to allow us to do some really interesting things together.’ That turned out to be true, and the tools he brought were the use of NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) as a way of measuring metabolic flux using stable isotope-labeled substrates.

I am particularly happy to be recognized for innovation. I think all scientists want to be viewed as innovative in what they do. So that’s certainly quite pleasing. And, of course, it’s fine for me to receive the recognition as a longtime leader of a group but none of it would be possible without a lot of contributions from a lot of people.

Having Dean on sabbatical in my lab brought home to me that there’s an emerging horizon of new metabolic research technologies…and this was more than 20 years ago. This was sort of the birth of my recognition of a new emergent field called metabolomics that was going to be very impactful and very promising. So, when I came to Duke in 2002 to head the Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center, which is now part of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute that I also lead, one of the stated goals that I had in being recruited was to build a world-class metabolomics lab and I think over time that’s what we’ve done.

We were one of the first into the game of applying a broad array of metabolomics tools to study cardio-metabolic diseases, both in animal models and in humans. Over time, I think we’ve made a substantial impact, and that’s perhaps why I’m being honored with this award.

EN: This year, the Society has awarded Laureate honors to two colleagues from the same institution. Endocrine News recently profiled your colleague Donald McDonnell, PhD, who was awarded the Outstanding Translational Research. What’s it been like at Duke since you both learned about your awards?

CN: Donald is a really good friend, in addition to being a great colleague. He’s chair of the Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology. I’m head of the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute and we have collaborated productively over the years. We were both really tickled by the fact that we won the same year.

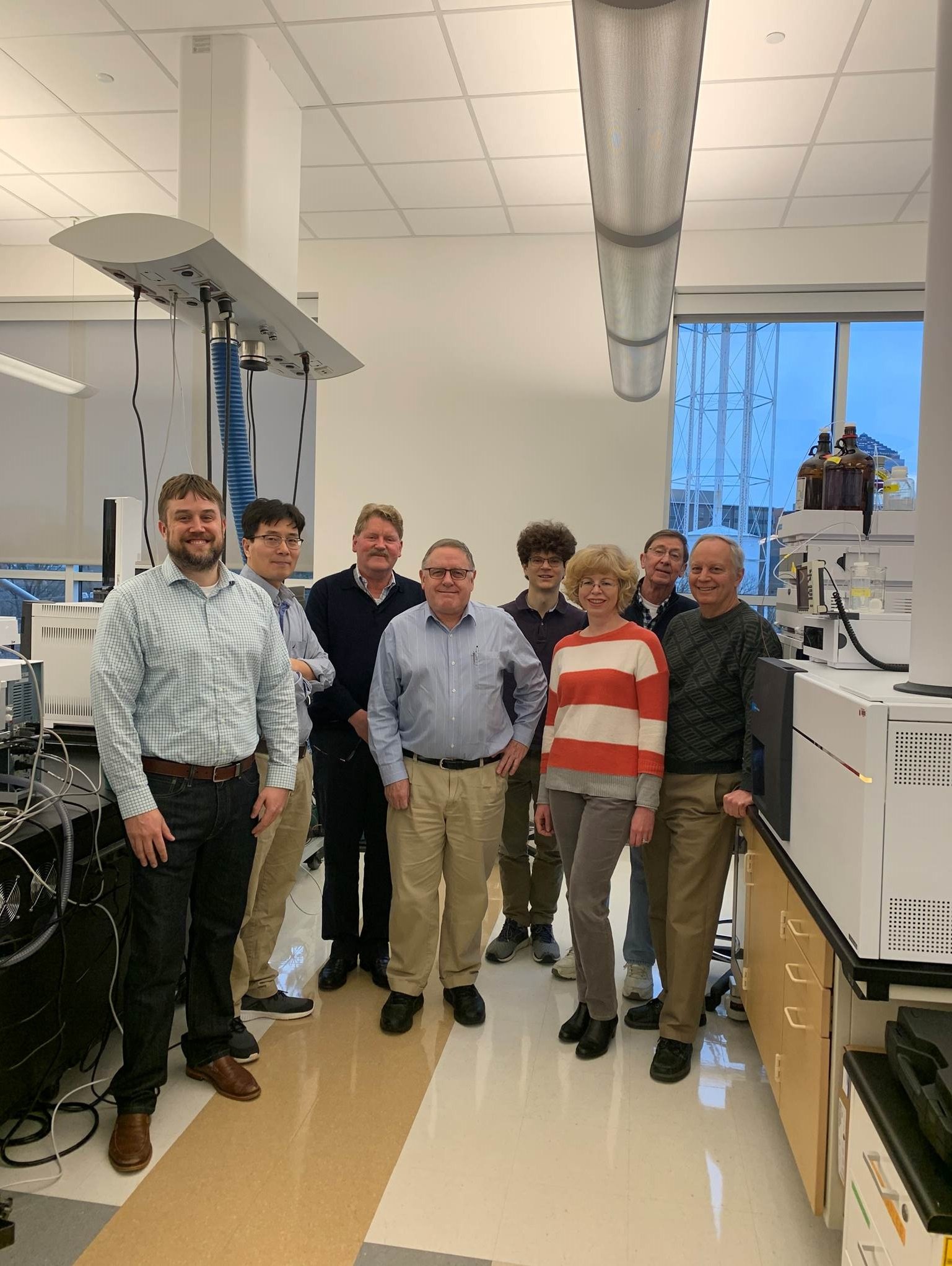

EN: How many scientists and students do you lead at Duke?

CN: Our metabolomics lab has about 10 people. Five or six PhDs and an equivalent number of technicians in the core lab, and any recognition of me needs recognition of others who have built a remarkable repertoire of technologies. In addition to that, I have my own basic science laboratory that works in cell and animal models, and has varied over the years from about 10 people where it is now, to as many as 16 to 18 senior scientists and students. I’ve worked with some incredibly talented people over the years — about 30 PhD students and 30 fellows. I have been very lucky in that regard.

—Fauntleroy Shaw is a freelance writer based in Carmel, Ind. She is a regular contributor to Endocrine News.