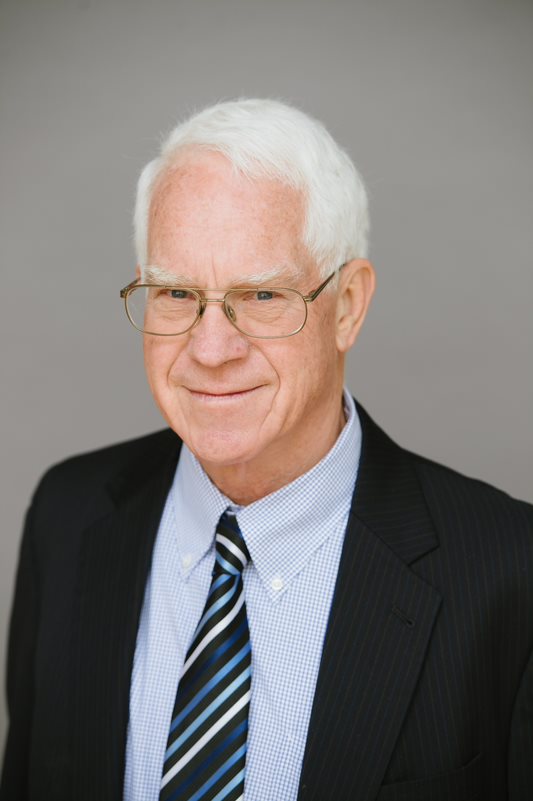

When Endocrine Society past-president Richard J. Santen, MD, achieved “emeritus” status at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, he was far from being done with practicing medicine. That’s when he decided to continue seeing patients throughout southwest Virginia from the comfort of his home and with help from telehealth technology and the Federally Funded Community Health Centers program.

About six years ago, a Emma Eggleston, MD, a medical fellow working with Richard J. Santen, MD, professor emeritus of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, pointed her car in the direction of southwest Virginia to attend a health fair and treat patients. She reported back how little exposure and access the patients had to endocrinologists and other specialists, so Santen decided that during his phased retirement that he would return to the area himself to take care of patients with diabetes.

Southwest Virginia is a rural, mountainous region with beautiful vistas and welcoming people, but this is also an area where incomes are below the national average (more than half the households are below the poverty line) and there is little to no internet. But the clinics there are federally funded and have some infrastructure that can be built upon, and it struck Santen that a telemedicine program could in fact be implemented, maybe just not conventionally.

So, Santen and his wife took two cell phones – one on T-Mobile and one on Verizon – and drove around southwest Virginia testing the cell phone towers. Santen then talked to a company called Telcare, which allows patients with diabetes to stick their finger and download their glucose level that resides on the meter until they can reach a cell phone tower. “That was the eureka moment,” Santen says. “That’s how we got around the problem of having no internet there.”

For the past six years, Santen has run a telemedicine clinic from Charlottesville where he can treat patients at six rural clinics in southwest Virginia that are part of a program called Federally Funded Community Health Centers. There are about 1,400 more of these Federally Funded Community Health Centers in underserved areas across the country. Santen’s goal is for other retired and semi-retired endocrinologists to join him and help rebuild, or at least reinforce, the endocrinology workforce to better treat these patients. “This is a real opportunity to improve the health of a group in the United States that is quite unhealthy and underserved,” Santen says.

Mitigating the Gap

In 2014, a paper by Vigersky et al. appeared in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism that concluded, “There are insufficient adult endocrinologists to satisfy current and future demand. A number of proactive strategies need to be instituted to mitigate this gap.” A 2022 paper in JCEM by Tsai et al. reported that there are about 8,000 currently active endocrinologists in the United States, “which amounts to 41,460 individuals in the general population who may receive potential care by each endocrinologist.”

“You talk to anybody who’s retired, and they’re okay for a couple of years — play golf, play bridge, take trips. They miss interacting with patients. And giving those individuals the opportunity to come back and interact with the patients again, in a situation where you’re not really pressed for time and you can get to know people, it’s beneficial for the retirement process also.” – Richard J. Santen, MD, professor emeritus of Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

Santen tells Endocrine News that compounding the problem is that many endocrinologists will want to go work in big cities like New York City or Los Angeles — places with more resources where they can make more money — as opposed to rural areas. That’s where the proactive strategy of bringing endocrinologists out of retirement comes in – he calls this “rebooting.” Physicians can retire in New York or anywhere in the country and treat patients in their home without ever having to step foot out of their front door.

“The opportunity is to fill that gap without having to train another whole generation of endocrinologists,” Santen says. “To some extent, it’s a stopgap. But it allows another population of endocrinologists to continue to benefit patients. When an endocrinologist retires, that’s 40 years of wisdom in taking care of patients, which then is not utilized to help anybody. The opportunity is that when a retired physician can come back, not have the hassles of a big hospital and its pressure, and not have the hassles of electronic medical records. They can treat patients from their homes or their studies.”

The Geography of It All

Santen again points to the Federally Qualified Community Health Centers program as the framework for this endeavor. This is a $29-billion program that hires physicians, nurse practitioners, nurse educators, nutritionists, and psychiatrists, has cameras for retinopathy, and takes care of patients who don’t have insurance or even money. “The infrastructure from [the six clinics in southwest Virginia] makes it possible that I can call the patient, make an evaluation, then have a liaison with two spectacularly good, certified diabetes nurse educators who then serve as a liaison between myself and the physicians,” Santen says. “What I’d like to do is to roll out this program around the country using the template that I’ve set up.”

And Santen knows there may be some hesitation among his retired colleagues. In a piece he submitted to the Journal of the American Medical Association for the special feature “A Piece of My Mind,” titled “Rebooting Retirees,” Santen writes that whenever he suggests this idea to fellow physicians, “I’m usually met with a cautious nod of agreement and then a pause as I see them ponder the seemingly obvious dilemma.” He acknowledges the geography of it all, but he also knows that some retired endocrinologists may also be apprehensive about learning a technology they’re not familiar with, or how they’re going to make money.

To the first point, Santen says that the telemedicine part is quite simple. Visits can be done over Zoom or Jabber, or a doctor can simply talk to a patient on the phone, the patient reads off their blood sugar numbers, and the nurse educator can take it from there. Santen also suggests having someone he calls a “navigator” to deal with the managerial side of things (renewing medical licenses, etc.).

As for the finances, Santen says that he sees this as more of an altruistic venture, but he notes that most retired physicians have pensions, and he believes that most would be willing to help these patients pro bono. Santen was hired by the Federally Qualified Health Center, and they pay him a monthly salary. “It’s enough money to pay for my medical malpractice insurance for my dictating equipment, for revising my medical license, and everything else,” he says. “It doesn’t make money for me. It’s neutral.”

Overcoming Communication Barriers

In six years, 268 patients have been referred to the Santen’s telehealth clinic by their primary care providers. Fifty patients remain in the program, while 139 patients have completed the program after reducing their hemoglobin A1C levels from 10.3 to 7.8% on average. After the six-month, self-management program, the patients are returned to the care of their primary care physicians or nurse practitioners. About 30% of patients were discharged prematurely because of noncompliance.

“To some extent, it’s a stopgap. But it allows another population of endocrinologists to continue to benefit patients. When an endocrinologist retires, that’s 50 years of wisdom in taking care of patients, which then is not utilized to help anybody. The opportunity is that when a retired physician can come back, not have the hassles of a big hospital and its pressure, and not have the hassles of electronic medical records.” – Richard J. Santen, MD, professor emeritus of Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

One of the problems Santen ran into early on was phone tag with patients. “For the first three years, I was really frustrated,” he says, “I would have to call people back, and we had phone tag. Finally, I said to myself, ‘What I should do is give the patient a telephone call appointment, a specific day, and a specific time. They would call me, and I would then be ready with their records.”

Santen says for the 70% of patients who have completed or remain in the program, the calls were regular and substantive. But 30% of those patients called maybe once or twice, realized how intensive the program is, and weren’t motivated to continue. “They’re human beings,” he says.

Santen goes on to say that lack of education or not being fluent or proficient in English remain barriers, and that financially challenged patients can grow frustrated after navigating a healthcare system without insurance and therefore providers who could take care of them, and they feel pushed around.

Rebuild, Reignite

In 1973, the television series The Six Million Dollar Man premiered, with the catchphrase: “We can rebuild him; we have the technology.” There’s a similar feeling in the endocrine space here in 2023; we now have the technology to rebuild the endocrinology workforce, from telemedicine to glucose meters that talk to cell phones and other devices to computer algorithms that can tell physicians just how much insulin their patients should be on.

For Santen, this technology can also help retired physicians continue their wisdom and reignite their passion for treating patients, on their own terms, and on their own schedule. These endocrinologists can dedicate as much time as they wish to seeing their patients, from three hours to 20.

“You talk to anybody who’s retired, and they’re okay for a couple of years — play golf, play bridge, take trips,” he says. “They miss interacting with patients. And giving those individuals the opportunity to come back and interact with the patients again, in a situation where you’re not really pressed for time and you can get to know people, it’s beneficial for the retirement process also.”

Bagley is the senior editor of Endocrine News. He wrote about how Antonio Bianco, MD, is rethinking hypothyroidism in the January issue.