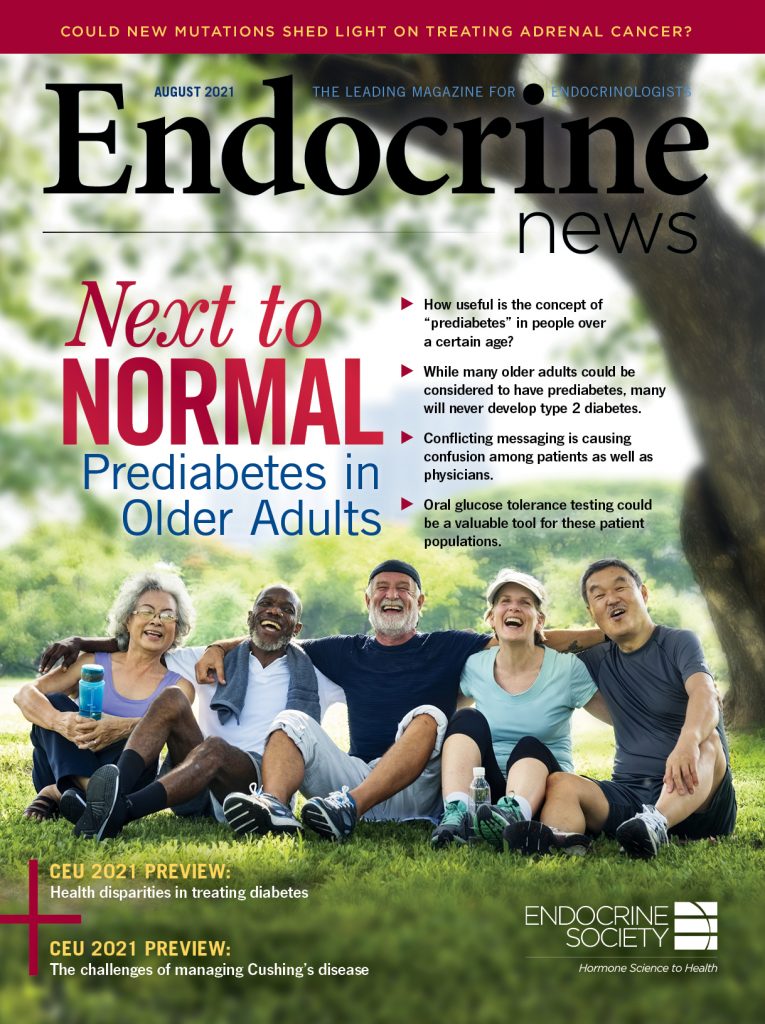

Although more than half of Americans over 65 meet criteria for prediabetes, most of them will not progress to developing diabetes. While conflicting messages abound regarding prediabetes, the Endocrine Society recommends an oral glucose tolerance test for those older patients at greatest risk for developing diabetes.

The scientist who helped popularize the term prediabetes now calls that effort a “big mistake.” His concern gained new attention when a recent study found that older adults whose hemoglobin A1c levels put them in the prediabetes category are much more likely to return to normal glycemic levels or die than develop diabetes. The study was one more in a string questioning the value of a diagnosis of prediabetes in this population.

But the Endocrine Society guideline on treating diabetes in older adults notes an often-overlooked aspect of the most common test used in screening for diabetes: As people age, their red-blood-cell life cycles change in ways that can render hemoglobin A1c results unreliable, with results that can mislead in both high and low directions. That’s why the guideline suggests following up with an oral glucose tolerance test in patients believed to be at risk for diabetes, according to Marie E. McDonnell, MD, director of the diabetes program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Mass., and a member of the Endocrine Society guideline committee. “The issue is not so much about prediabetes, it is more about not missing diabetes,” McDonnell says.

- More than half of older adults meet the criteria for a diagnosis of prediabetes, but most will not progress to developing type 2 diabetes.

- Clinicians and patients receive conflicting messages about prediabetes. American Diabetes Association guidelines say it “should not be viewed as a clinical entity,” but critics charge that the term’s marketing says otherwise.

- Hemoglobin A1c levels can be misleading in older adults, so an oral glucose tolerance test can be valuable in identifying which patients are at truly greater risk of developing diabetes, according to an Endocrine Society guideline.

Popularization of the Term

Prediabetes itself does not have clinical consequences, but this distinction can be easily missed in what some call the marketing effort for the condition. Richard Kahn, PhD, was the chief scientific and medical officer at the American Diabetes Association in 2001 when the ADA was trying to raise the alarm about the danger signs on the road to developing diabetes.

At the behest of the ADA’s head of press relations, Kahn met with other experts who decided to coalesce around using the term prediabetes to replace technical phrases like impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose as a way to drive home to the public their concern about the rising threat of diabetes. But the term has since taken on a life of its own that was unforeseeable at the time, says Kahn, who served as ADA’s chief medical officer for nearly 25 years and is now clinical professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The ADA defines prediabetes as an Hb A1c level of 5.7% to 6.4% (with type 2 diabetes starting at 6.5%) or a fasting plasma glucose of 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L). With more than 50% of Americans over age 65 meeting these criteria, the term has become controversial with critics saying the “pre” part is misleading in this population, as evidence has accumulated about the low risk that those with slightly elevated blood glucose levels will go on to actually develop diabetes.

A prospective cohort analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine in February that followed 3,421 adults with a mean age of 76 for a 6.5-year follow-up period highlighted this question about the true level of risk.

“The people who had prediabetes at baseline were actually more likely to return to normal glucose levels or die after six years of follow-up instead of progressing to diabetes,” lead study author Mary R. Rooney, PhD, MPH, a postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Md., tells Endocrine News. “Even across all the different definitions of prediabetes, these definitions didn’t really capture risk of progression to diabetes well.”

A Risk Factor Twice Removed

An editorial accompanying the study notes that not only do HbA1c levels in the prediabetes range pose no risk of complications, but diabetes itself can be controlled. Kenneth Lam, MD, and Sei J. Lee, MD, MAS, both of the University of California, San Francisco, write that it is the “end-organ vascular complications that result from years of poorly controlled diabetes that cause symptoms. Therefore, the modern definition of diabetes is conceptually closer to being a risk factor itself (e.g., something that portends future disease) than an illness (e.g., something that patients experience). Prediabetes, then, is a risk factor twice removed; it is a risk factor for diabetes, which itself may be most accurately described as a risk factor for end-organ vascular disease.”

“The people who had prediabetes at baseline were actually more likely to return to normal glucose levels or die after six years of follow-up instead of progressing to diabetes. Even across all the different definitions of prediabetes, these definitions didn’t really capture risk of progression to diabetes well.” – Mary R. Rooney, PhD, MPH, postdoctoral fellow, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Md.

Lam agrees with Kahn that the way prediabetes is marketed is questionable. This marketing is highlighted by a website that asks “Could you have prediabetes?” with a “take the test” risk calculator sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Medical Association, and Ad Council (doihavediabetes.org). A 2016 study in JAMA Internal Medicine estimated that the calculator would score 60% of Americans 40 years and older and 81% of those 60 and older as at risk for prediabetes.

This messaging is also present in the ADA’s standards of diabetes care. The standards of care lump the two together under a bold-faced subtitle, “Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes.” Yet the smaller text says: “Prediabetes should not be viewed as a clinical entity in its own right but rather as an increased risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

Treatment of Diabetes in Older Adults: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline is available at: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/104/5/1520/5413486

“The ADA guidelines specifically state that prediabetes is not a disease, but the marketing around prediabetes strongly suggests that it is a disease,” Lam says.

It is easy to find examples of internists ready to prescribe metformin based on Hb A1c levels in the prediabetes range, even those barely above normal, New York Times health writer Paula Span found in reporting on the February study. The use of drugs in patients with prediabetes contradicts the Endocrine Society practice guideline recommendations for older adults with diabetes, and notes that the FDA has not approved metformin for prevention. Drug treatment is generally not recommended because the evidence indicates it is not nearly as effective as diet and exercise in prediabetes, particularly in older adults, according to McDonnell. (The ADA standards say metformin should be considered for prevention, especially in obese patients and those under 60 years old.)

The JAMA Internal Medicine article is one of a string of studies questioning the relevance of the prediabetes diagnosis in older adults. A 2018 Cochrane Library review of 103 studies found that “because people with prediabetes may develop diabetes but may also change back to normoglycemia almost any time, doctors should be careful about treating prediabetes because we are not sure whether this will result in more benefit than harm.”

Revised Standards Coming?

The ADA declined repeated requests from Endocrine News to comment on how the ADA standards of care treat prediabetes. However, the New York Times quoted Robert Gabbay, ADA’s current chief scientific and medical officer, as saying that the professional practice committee will review the recent JAMA Internal Medicine study and perhaps adjust the guidelines considering that the risk of older adults of developing diabetes “may be smaller than we thought.”

Gabbay reiterated the often-expressed view that a prediabetes diagnosis is a valuable tool because it can motivate people to try to bring their blood sugar down through the healthy lifestyle choices that everyone should be making. Lam counters that clinicians should not mislead people about their condition or use scare tactics to try to motivate them.

McDonnell notes that glycemia has consequences on a continuum, and that it can still be useful to know that a significant percentage of patients with prediabetes will go on to develop diabetes. She says that clinicians can confirm whether a high Hb A1c is a false flag or whether it indicates “real” prediabetes — or even diabetes.

“It is hard to argue against screening for diabetes. We know that there is a significant number of undiagnosed diabetes in the older adult population, and we know that about a quarter of people over 65 have diabetes.” – Marie E. McDonnell, MD, director, Diabetes Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Mass.

The Endocrine Society guideline emphasizes that today’s older adults can easily live another 20 years. That is plenty of time to develop the complications of diabetes, which appropriate treatment can mitigate.

The Endocrine Society and ADA guidelines both recommend a lifestyle program for prediabetes patients. McDonnell notes that patients can benefit from a diagnosis of prediabetes because it means that Medicare will cover enrollment in a diabetes prevention program. “It might get them free access through Medicare to a lifestyle behavior modification program that will focus on eating well and exercising, and that has benefits way beyond glucose control,” McDonnell says. Because older adults derive a broad range of benefits from exercise and maintaining healthy body weight, McDonnell suggests that the identification of prediabetes in this group is benign if not beneficial.

Defining the Parameters

“It is hard to argue against screening for diabetes,” McDonnell says. “We know that there is a significant number of undiagnosed diabetes in the older adult population, and we know that about a quarter of people over 65 have diabetes.”

But the parameters used in the screening can make a big difference, according to a 2020 BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care article that compared the results of using the different cut-offs in the ADA and World Health Organization definitions of prediabetes. The authors noted that the “main difference” in the two definitions of prediabetes was the threshold of the glycemic index.

For fasting glucose, the ADA threshold is 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) whereas the WHO threshold is 108 mg/dL (6.0 mmol/L). The study applied the two definitions to about 9,000 people over age 45 without diabetes from the general population in the Rotterdam Study in the Netherlands. The ADA criteria diagnosed 40% as having prediabetes, compared with 16% using the WHO criteria. Among those classified as having prediabetes, the 10-year risk of developing diabetes was 14% using the ADA definition, compared with 25% using the WHO definition, and lifetime risk was “substantially lower in ADA-defined prediabetes.”

As a geriatrician, Lam notes that the concept of risk — and competing risks — is a key to treating the individual, not the number. The approach when test results indicate prediabetes should be very different in a frail patient in their 80s compared with an obese 65-year-old.

Seaborg is a freelancer writer based in Charlottesville, Va. In the July issue, he wrote about the CEU 2021session discussing the use of testosterone therapy in female patients.