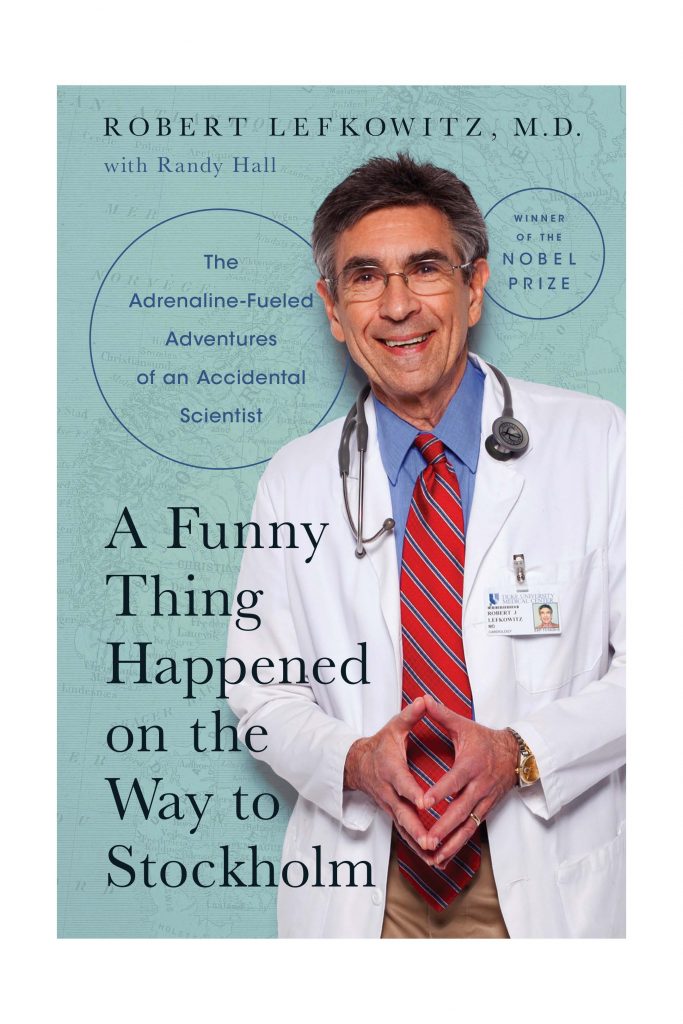

Robert J. Lefkowitz, MD, first got into research because of the Vietnam War. As described in his new book A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm: The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist, he joined the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) to avoid being sent to Vietnam as a military doctor in a war he did not support. His service at the NIH ignited a passion for research that has burned for five decades and resulted in a Nobel Prize. However, recent downturns in the numbers of physician-scientists suggest that we cannot rely on such serendipity in exposing physicians to research.

In the April issue, Endocrine News chatted with Lefkowitz about his career, what it’s like to win the Nobel Prize, and the next generation of scientists. Here now are excerpts from Lefkowitz’s new memoir, describing his journey from clinician to physician-scientist, followed by his thoughts on how to grow the ranks of physician-scientists in the modern day.

I had yearned to attend medical school since the age of 8, but had not the slightest bit of interest in research during my medical school days. I was determined to become a practicing physician, and research seemed like a distraction from my single-minded goal. Thus, during my medical school training at Columbia, I performed no research at all and simply remained laser-focused on honing my clinical skills.

As medical school wound down in the spring of 1966, my family’s future was endangered by a looming threat: the Vietnam War. At that time, all graduates of American medical schools were required to enter the military to serve a year in Vietnam. There was no lottery system in this “doctor draft”—the military had an acute shortage of doctors, so every medical school graduate was mandated by law to serve. I believed in the importance of serving one’s country but also dearly wanted to avoid being separated from my young family and sent halfway around the world for a year to support a war that I and most of my classmates believed was wrong. I felt a growing sense of trepidation and searched for some kind of alternate path that might allow me to serve honorably, avoid directly participating in the war, and also stay close to my family.

There were several ways for doctors to avoid serving in Vietnam. Medical school graduates were allowed to request a one- or two-year deferment to complete their internships and up to one year of residency training. After that, though, service in Vietnam was required unless some other arrangement was made. One attractive possibility was to gain a commission in the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), which was considered part of the US military and thus fulfilled one’s draft obligation. USPHS physicians could work as prison doctors in the federal penitentiary system, help to track global pandemics at the Centers for Disease Control, or conduct research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Despite my previous lack of interest in research, I decided to pursue this last option.

I hoped to become an academic physician, maybe even a chair of Medicine at a top medical school someday, and was becoming aware that such positions required at least some research experience. Most of the prominent doctors who trained me at Columbia were alleged to have done research at some point in their pasts, and a handful were even supposedly still active. For example, one of my attending physicians, William Manger, was a subject of fascination amongst the medical students. Whenever he walked past, you’d hear people say in hushed tones, “I hear he does research.” It clearly gave him a special cachet and cool factor.

Manger was also notable because he was the heir to a hotel fortune. He dressed sharply in three-piece suits, complete with a pocket watch dangling on a gold chain. Late in my last year of medical school, he invited several of us who were on rounds with him over to one of the Manger hotels downtown. After we enjoyed lunch in the luxurious dining room, Manger casually asked, “Would you like to see my laboratory?” We were curious, of course, and even more curious when he got into the elevator and pressed the button for the penthouse. When the elevator doors slid open, we strode into a spectacular suite that had been converted into a research lab. Hundreds of glass beakers were glinting in the abundant light, and the windows on all sides looked out over jaw-dropping views of New York City. I was in awe, and began to think that maybe research wasn’t so bad after all.

Having decided that a bit of research might be a nice addition to my resume, I submitted my application to the NIH. I was accepted for an interview and drove to Bethesda, Maryland, for my interviews on July 1, 1966. Unfortunately, the first of July also happened to be the start date for my internship at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. As if beginning my internship wasn’t stressful enough, I had to miss my first day (and beg someone to cover for me) in order to conduct my interviews in Bethesda.

The interview process was a match-based system: applicants had to rank the group leaders with whom they wanted to work, and the group leaders in turn had to rank all the applicants. It was a highly competitive process, with hundreds of the best and brightest young doctors across the country applying for a limited number of slots.

My interviews at the NIH went poorly. For one thing, I had no research experience at all, which I began to realize was a major negative when interviewing for a research position. I had to explain over and over again to different NIH scientists why I hadn’t bothered to take advantage of the various research opportunities that had existed at Columbia. My lack of research experience was compounded by my lack of enthusiasm, as I wasn’t actually very excited about research but rather just trying to bluff my way through the process by pretending to be enthused.

The toughest interview of the day was my last, with a tall, hyperkinetic scientist named Jesse Roth. He asked why I wanted to come to the NIH. I said the words I thought he wanted to hear.

“My goal is to become a triple threat: I want to be a great physician, great researcher, and great administrator.”

“That’s bullshit,” Roth replied. “You’ll never be great at all three. You have to choose. Which would you choose if you could only be great at one?”

I was taken aback by his tone and stammered my way through an incoherent answer. When I left Roth’s office and staggered back to my car, I was certain that I’d screwed up and wouldn’t receive an offer for one of these coveted positions. I felt an impending sense of doom that I would soon be torn away from my family and sent on a tour of duty in the jungles of Vietnam.

***

During the first few months of my internship at Columbia, as I honed my clinical abilities as a physician overseeing a whole roster of patients each day, I kept waiting to learn whether my next move would be to the NIH or Vietnam. Finally, a phone call came for me at the hospital and someone yelled down the hall that it was from the NIH. I raced to the phone and picked up the receiver. The call was from Jesse Roth himself, and he wanted to know if I would be interested in joining his research group. I accepted on the spot and raised my arms in triumph when I hung up the phone.

A short time later, I moved my family from New York to Bethesda to begin my service. The PHS-commissioned officers of that era who served at the NIH were known as the Yellow Berets. The sobriquet was a play on the Green Berets, with the color change meant to suggest we were too scared to fight. Avoiding service in Vietnam was not an act of cowardice, though. For most, it was an act of conscience. The war was immensely unpopular, and massive antiwar demonstrations in downtown Washington, D.C., were a common occurrence during my two years of service.

Young doctors across the country were desperate to avoid being shipped off to war, so the NIH had received thousands of applications that year for less than two hundred slots. The intense competition meant that those selected were the cream of the crop, and I felt honored to be part of this august group. As it has turned out, a total of ten Yellow Berets have gone on to become Nobel Laureates, which is impressive considering the relatively small size of the program In addition to myself, the Yellow Berets who have won Nobel Prizes are Michael Brown, Joseph Goldstein, J. Michael Bishop, Harold Varmus, Alfred Gilman, Stanley Prusiner, Ferid Murad, Richard Axel, and Harvey Alter. Beyond these ten, many dozens more Yellow Berets have been inducted into the National Academy of Sciences and received other major research accolades. Given the outsized success of this program, it is worth considering if perhaps there was something special about exposing young physicians to full-time research at an early stage in their training.

During this era, of course, I had no inkling that I or any of my compatriots would end up accomplishing anything of significance. For my first year at the NIH, I was miserable. I missed seeing patients and felt like I was all thumbs in the lab. However, something changed during my second year. I began overcoming the technical troubles that had plagued me during my first year and suddenly started making progress in my studies with Jesse Roth and Ira Pastan on studying the actions of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). In short order, I successfully purified radiolabeled ACTH, showed that the labeled ACTH was biologically active, and then developed one of the very first assays for studying the binding of a hormone to its receptor. Later in my career, I realized that this is often how research works: you experience nothing but failure for weeks or months, and then suddenly you overcome a technical hurdle and everything starts moving like wildfire. These were heady months, as I felt intoxicated by the knowledge that I was exploring new realms of research where none had previously trodden.

I published three papers with Roth and Pastan based on this work, completed my USPHS service, and headed off to Massachusetts General Hospital to complete my residency and also perform a fellowship in cardiology. Once back in a hospital setting, I reveled in the fact that I was living my childhood dream, enjoying the clinical work and loving my interactions with the patients. At the same time, though, I began to feel vaguely dissatisfied. I realized that I missed research. I missed the stimulation of trying to do something that nobody had ever done before. I missed the into-the-wild-blue-yonder feeling of improvising experiments on the fly and going where the data took me, which is the essence of research. Clinical medicine is the polar opposite of research in this regard: in medicine, you typically try to follow the standard operating procedure. The goal is not to do something creative, but rather to follow established protocols for helping patients. In this way, you enhance patient outcomes and also protect yourself (and the hospital) from being sued for malpractice. However, the cautious approach that is necessary for practicing good medicine can sometimes feel constraining, especially compared to the boundary-pushing adventures of basic research. As a clinician, you hear the same stories of received wisdom over and over again; as a scientist, you have the opportunity to start writing your own stories.

I was experiencing creative urges that were very surprising to me. For most of my time at the NIH, I had been miserable and only wanted to get back to clinical medicine. Now that I was back in the clinic, I could think only about research. It was an epiphany for me to catch myself daydreaming about experiments I wanted to perform. I had several elective rotations coming up as I entered the second half of my residency year at Mass General, and I began wondering if I might be able to use some of that elective time to squeeze in a little research.

I had a clandestine meeting with Edgar Haber to discuss research possibilities. Haber was the chief of the Cardiology Division at Mass General and an accomplished researcher who had worked at the NIH with Nobel Laureate Christian Anfinsen. He had a sizable research lab and told me that he would be happy to give me a lab bench so that I could do some experiments. He and I both understood that this arrangement was against the rules: I was being paid from hospital income, not a research fellowship, so I was supposed to be doing my clinical electives and seeing patients. However, I really wanted to do some research, and Haber really wanted an extra pair of hands in his lab, especially from someone with my pedigree of having published papers with Roth and Pastan at the NIH.

Despite the fact that research was forbidden, I began sneaking into Haber’s lab and conducting experiments. Soon I was spending almost all my time in the lab. One evening, while I was surreptitiously working late in the lab, disaster struck: I got busted by the house staff director, Dan Federman. He was taking an unusual route through the building because it was raining, and happened to walk right by my laboratory as I was crossing the hallway while carrying a rack of test tubes.

“Lefkowitz! What the hell are you doing here?” he demanded. “I heard rumors that you were doing research . . . You know that’s not allowed! See me in my office at 9:00 a.m. tomorrow.”

***

You’ll have to read the book to see how the story ends (spoiler alert: I was not kicked out of my residency). However, it should be clear from the stories told above that the start of my research career was marked by copious amounts of luck and serendipity. The conditions that led to my accidental diversion into research cannot easily be replicated in the present day. For example, there is no wartime draft forcing young physicians to compete for research fellowships as there was back in the 1960’s. And unfortunately, physician-scientists are becoming a vanishing breed: in the 1980’s, 4-5% of all physicians were involved in research, but this number has fallen to ~1% in recent years. This trend is quite unfortunate, as physician-scientists account for 37% of all Nobel Prizes won in Physiology or Medicine.

How can we do a better job grooming the next generation of physician-scientists? I have a few thoughts to share in this area. One key approach is to expose more young physicians and aspiring physicians to research. When I started in medical school, as described above, I never thought for a moment that I would have the slightest interest in research. It wasn’t until I was forced to try my hand at research that I fell in love with it and realized I had some ability in this area. Similarly, there are undoubtedly many young medical students out there right now who are focused on careers as clinicians but who have the potential to become future Nobel Prize winners if given the opportunity to fall in love with research.

My home university of Duke is amongst the minority of medical schools requiring a full year of research by all medical students in their third year. At Duke, the basic coursework is condensed into a single year, which means that students start their clinical rotations in the second year. The third year is dedicated to research, and then the final year is focused on clinical rotations. This model has been very successful at Duke, and in recent years has been copied by a number of other medical schools. As someone who began my medical career with zero interest in research until I was forced to try it, I can certainly appreciate the value of exposing medical students to research in order to see if they might discover a passion they didn’t know they had.

Another approach is to support “year out” programs for medical students where they can interpose a year of research between their second and third or third and fourth year of medical school. Unfortunately, an excellent such program, the Medical Fellows Program supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, was recently terminated. This leaves barely one such position available nationally for every 1000 medical students. I am the President of a new nonprofit foundation named the Physician Scientist Support Foundation (PSSF; http://www.thepssf.org/), which is working to re-establish such programs at the medical student level as well as to expand mechanisms to support junior faculty transitioning to independence in their research.

Beyond exposing young physicians to research, another key idea is that we need to have greater institutional support for physician-scientists. I was recruited to Duke in 1973 by Jim Wyngaarden, a leader who fiercely protected my time to ensure that I had sufficient hours to devote to research. A few years later, in 1976, I received support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which further protected my research time. Without such strong support from the Duke leadership and HHMI, I never would have been able to launch my research program focused on understanding how adrenaline acts through specific receptors.

Too many physician-scientists these days don’t receive the institutional support they need to thrive. Young physician-scientists require protected research time and also often need financial support for their research programs beyond just a two- or three-year startup package. Devoted mentorship from senior physician-scientists is another necessary ingredient. Such support takes concerted effort in the short term but can offer massive returns on investment in the long term by helping to launch the careers of physician-scientists who will go on to become pillars of a university’s biomedical research community and bridge the gap between the clinicians and basic scientists on campus.

In addition to greater institutional support, physician-scientists also require stronger support at the national level. There are worthy mechanisms at the NIH for supporting physician-scientists, and these mechanisms need to be expanded to help reverse the declines in the physician-scientist population that we have witnessed over the past several decades. Moreover, private foundations should raise their games in this area as well. More money isn’t the whole answer, but it is a necessary ingredient for encouraging physicians to stay in the game and pursue vigorous research efforts.

We live in an age of increasing specialization, which makes those who can straddle two worlds all the more valuable. Grooming the next generation of physician-scientists will require a redoubling of our efforts in medical school curriculum design, institutional support from academic leaders, and financial support from funding agencies. The world is crying out for such efforts to bear fruit, as there has never been a more important time to grow the ranks of physician-scientists to help spearhead the fight against human disease.

— Reprinted with permission of Robert J. Lefkowitz, Randy Hall, and Pegasus Books.