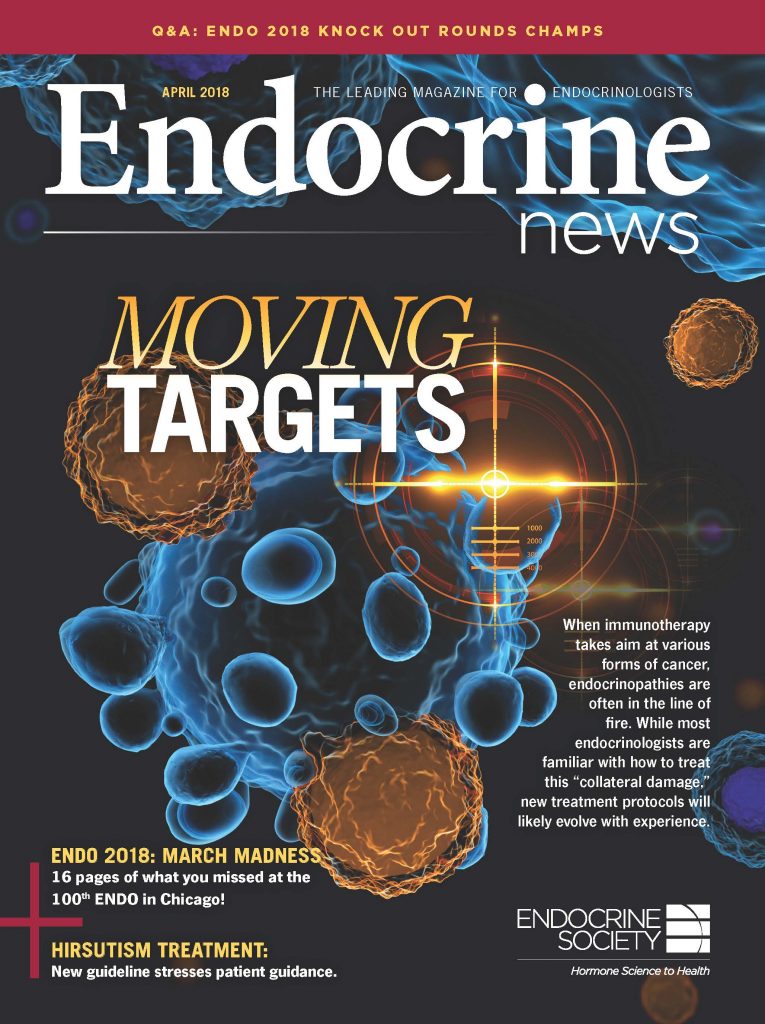

Immune checkpoint inhibitors unleash the immune system on cancer to great effect and increasing survival rates. However, but switched-on immune cells set their sights on other targets, many times the endocrine system.

Immunotherapy has boosted survival rates for some of the most recalcitrant forms of cancer with an approach that is revolutionizing the field. But as the treatment beats back cancer, serious side effects strike many patients. Endocrinopathies — particularly involving the thyroid, pituitary, and pancreas — are among the most common and important of these.

“We in the endocrinology community need to be familiar with the basic idea behind these medications our oncology colleagues are utilizing,” says Matthew J. Levine, MD, of the Scripps Clinic division of diabetes and endocrinology in San Diego. “They unleash the immune system to fight malignancies. And while they seem to be very effective in combatting the malignancies for which they are designed, they cause a lot of endocrine-related adverse events.”

Awakening T Cells

Immunotherapy attacks cancer’s secret weapon — its ability to hide from the immune system by keeping immune cells from recognizing tumor cells as invaders. The immune system contains checks and balances that keep the body from harming itself, and several years ago researchers discovered some “checkpoints” on T cells that act as brakes on their aggressiveness, including the proteins PD-1 (for programmed death 1) and CTLA-4 (for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4). Many tumor cells express the ligands for these checkpoint receptors, and when triggered, the checkpoint proteins provide a brake or “off switch” that inhibits the T cell from attacking the tumor cell.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer are exploding in use. Their success could revolutionize the field.

- As immunotherapy unleashes the patient’s immune system to attack cancer, T cells can also attack the patient’s other tissues, with the endocrine system at particular risk.

- Most endocrinologists will be familiar with how to treat these endocrinopathies, but the protocols for treatment will evolve with experience.

Researchers exploited these discoveries to develop drugs they dubbed immune checkpoint (ICP) inhibitors — monoclonal antibodies aimed at PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 to block the proteins from binding to the tumor cells, thereby taking off the brake and allowing the T cell to recognize and attack the tumor cells.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the first ICP inhibitor in 2011, and the therapy is now in use for advanced or metastatic melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, kidney cancer, urothelial cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma. And they are in clinical trials for many other cancer types.

Targets in the Endocrine System

“Over the last two years there has been an explosion of using these drugs, and as a side effect of that treatment, we are starting to get a significant referral of patients to endocrine clinics with the onset of new autoimmune problems that are targeting the patient’s endocrine system,” says Mark S. Anderson, MD, PhD, a professor and researcher at the University of California San Francisco Diabetes Center.

“We think now that the immune system is really capable of mediating anti-tumor activity against almost any type of tumor,” Kaufman says. “There are some types that have been holdouts that haven’t responded, and we are trying to understand why that is the case. We think eventually most cancers might be amenable to at least some form of immunotherapy.” – Howard Kaufman, MD, immediate past president, Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer; faculty member, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

The problem is that when these drugs take off the brakes, the T cells can attack the patient’s own tissues — and the thyroid, pituitary, and adrenal glands as well as pancreatic islets are of particular concern for these immune-mediated problems.

When Levine and his colleagues at Scripps reviewed the charts of 103 patients who received ICP inhibitors, they found that some 32% developed an endocrine immune-related adverse event. A 2016 study by Joshi et al. in Clinical Endocrinology found that thyroid dysfunction occurs in up to 15% of patients, hypophysitis in up to 9%, and adrenalitis in about 1%. Other reports put the incidence of type 1 diabetes at 1% or more.

The agents appear to affect tissues differently. CTLA-4 inhibitors are associated more with hypophysitis, whereas PD-1 blockade is implicated more in thyroid dysfunction.

The Joshi study found that the mean onset of endocrine side effects is nine weeks after the initiation of therapy, with a wide range of onset from five to 36 weeks. Levine’s team found that most endocrine adverse events occurred between the second and fifth infusion. Several occurred after the first infusion, and one occurred after 14 infusions. There are literature reports of problems occurring even later in the infusion process, so patients must be monitored through a wide time frame.

Treatment: Standard Yet Experimental

For the most part, recommended treatment for these conditions is generally the same whether they result from ICP treatment or develop on their own or under other circumstances. The treatment approach may depend on a condition’s severity and how soon it was detected, especially as it relates to whether the cancer treatment can continue.

“Sometimes the thyroid issues that come up as a result of these medications are consistent with thyroiditis — a transient phenomenon where a person can develop an overactive thyroid, then an underactive thyroid. By its nature, it normalizes over time,” Levine says.

Anti-CTLA-4 drugs: Ipilimumab

Anti PD-1 drugs: Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab

Anti PD-L1 drugs: Atezolizumab, Durvalumab, Avelumab

Hypothyroidism can be treated with conventional hormone replacement, and hyperthyroidism can also be treated conventionally.

Although some sources have recommended treating hypophysitis with high-dose glucocorticoid therapy, various studies have found that high-dose therapy did not improve outcomes. They suggest that physiologic glucocorticoid replacement dosing may avoid additional adverse consequences.

Primary hypoadrenalism due to ICP inhibitor treatment should be treated with conventional hormone replacement following current guidelines.

Unique Diabetes

The tripping of an autoimmune disease such as type 1 diabetes should come as no surprise, but Anderson says: “It’s remarkable how quickly it can happen. The glucose will be normal at one infusion and then sky high at the next. We are getting patients who have glucoses well over 500 mg/dL, diabetic ketoacidosis, and low insulin c-peptide levels. Taken together, this picture points to an acute onset of a unique form of type 1 diabetes.”

Although there seems to be interim consensus on treatment recommendations, Levine notes that the field is so new that it is lacking in protocols on treatment and about whether ICP treatment can be continued while side effects are treated. Patients generally receive panels of laboratory tests from their oncologists, but the field also lacks protocols on the extent and timing of testing. The question of how often the endocrinopathies are reversible and how many will require indefinite treatment is another that only experience will answer.

Early Treatment Pays

Patients need to be told to be frank about their symptoms and resist any temptation to hide them out of fear that they could be taken off the ICP inhibitors, according to Howard Kaufman, MD, immediate past president of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer and a faculty member at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston: “If we can intervene when the side effects are minimal, the likelihood that they will stay on the treatment is higher. With all of these side effects, the earlier they are identified and treated, the more rapidly they seem to come under control.”

“We in the endocrinology community need to be familiar with the basic idea behind these medications our oncology colleagues are utilizing. They unleash the immune system to fight malignancies. And while they seem to be very effective in combatting the malignancies for which they are designed, they cause a lot of endocrine-related adverse events.” – Matthew J. Levine, MD, Scripps Clinic Division of Diabetes and Endocrinology, San Diego, Calif.

Another challenge come from patients who don’t realize their symptoms are side effects of the ICP inhibitors or misunderstand their implications. “They go to the emergency room and say, ‘I’m on chemotherapy.’ The poor emergency room doctor may be misled or may not understand that immunotherapy is really different from chemotherapy,” Kaufman says. Kaufman gives his patients cards explaining about their ICP inhibitor treatment, but not everyone carries them.

Most endocrinologists are seeing these patients as a result of referrals from oncologists. But the potential for patients to show up at endocrine clinics seeking treatment for side effects will grow. ICP inhibitors are currently used mostly in large centers, but many more agents are in development and trials. As more come on the market and the indications for their use expand, they will inevitably spread to throughout the healthcare system and endocrinologists will need to be prepared to manage these patients.

“We think now that the immune system is really capable of mediating anti-tumor activity against almost any type of tumor,” Kaufman says. “There are some types that have been holdouts that haven’t responded, and we are trying to understand why that is the case. We think eventually most cancers might be amenable to at least some form of immunotherapy.”

Seaborg is a freelance writer based in Charlottesville, Va. He wrote about the Endocrine Society’s latest Scientific Statement on obesity in the March issue.