My mother was a nurse. She had a tendency to look at the world two ways: her way and the wrong way. The problem, such as it was, typically turned out to be that her way was the right way. It was both comforting and infuriating all at once. I feel like there are many of you out there who totally get where I’m coming from.

During the hot summers in southwest Alabama, when she would see me sitting on the couch, watching Good Times reruns with my hand jammed into a Golden Flake potato chip bag up to my elbow, she would encourage me to “go outside and play!” She told me I would feel better, and it was such nice weather, and it would be good for me, etc. To be honest, I didn’t realize how wise she was until after the summer of my freshman year in high school wrapped up and I experienced my first band camp. I started my sophomore year lean, tanned, and only a marginally better trumpet player!

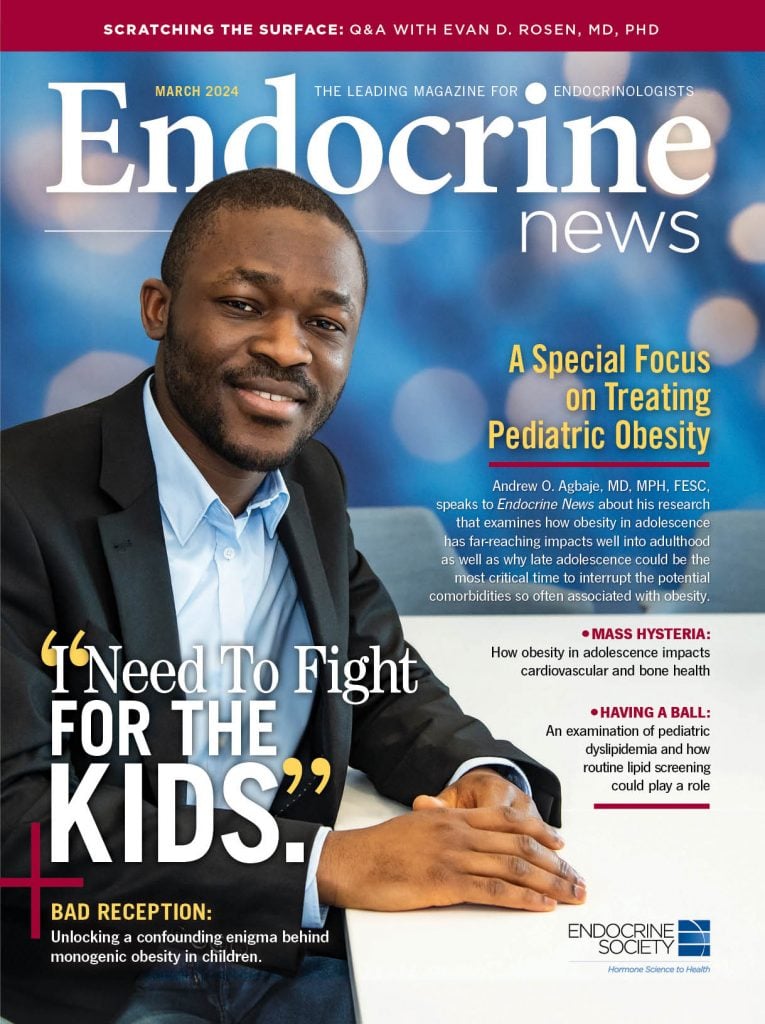

I relate this youthful tale of an abruptly ended life of sloth because so much of this issue focuses on the dangers of adolescent obesity, not to mention too much sedentary time for many adolescents with obesity. This month’s cover features Andrew O. Agbaje, MD, MPH, FESC, from the Institute of Public Health and Clinical Nutrition, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, at the University of Eastern Finland in Kuopio, whose research figures prominently in two studies published in the January 2024 issue of The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism that both address the dangers of the many complications associated with obesity in youth.

In “Having a Ball,” Kelly Horvath talks to Agbaje about his JCEM paper, “Associations of Sedentary Time and Physical Activity From Childhood With Lipids: A 13-Year Mediation and Temporal Study,” and he details the study’s findings, why some of the official guidelines are wildly arbitrary, and the need for more regular lipid screenings in pediatric patients. According to Agbaje, one out of five adolescents with obesity who eventually develop heart disease is “one too many, when this is preventable,” he says. “Also, when many of these heart diseases eventually occur, we can’t cure them, we can only manage them for life, which increases healthcare costs, yet it’s so cheap to measure cholesterol levels.” Current guidelines recommending cholesterol screening at age 40 are woefully misguided because by the time middle age rolls around, the damage has already been done to the cardiovascular system, and the healthcare cost burden spirals.

In “Critical Mass,” Eric Seaborg speaks to Agbaje about his other JCEM study, “DXA-based Fat Mass With Risk of Worsening Insulin Resistance in Adolescents: A 9-Year Temporal and Mediation Study,” where he says that body mass index measurements only tell part of the story; BMI does not give a true measure of the dangers of abdominal fat nor does it elucidate the benefits of muscle mass. “Fat mass drives insulin resistance, but muscle mass appears to reverse it in a very small way,” Agbaje says. “If we only use BMI, we will not be able to see that muscle mass is beneficial in lowering insulin resistance. … abdominal fat is twice as dangerous as total body fat. Every increase in abdominal fat raised the risk of insulin resistance, not just at the time point but progressively from age 15 to 24.”

The article also reports on a second JCEM study, “Insufficient Bone Mineralization to Sustain Mechanical Load of Weight in Obese Boys: A Cross-Sectional Study,” which details the impact of pediatric obesity on bone mineral density and content compared to average-weight children. The study shows that those children with obesity have a 25% higher risk of extremity fracture than children of average weight.

Senior Editor Derek Bagley examines a New England Journal of Medicine study that looked into the cases of two very different children — one from Qatar and one from Austria — who presented with unusually high leptin levels that the researchers discovered were due to inadequate binding with receptors (“Bad Reception”). It wasn’t until the young patients’ family history was considered that the researchers were finally able to put the pieces of the puzzle together. Once this binding “defect” was realized, it was like a totally new idea from a biological point of view that had never been described before, according to researcher Martin Wabitsch, MD, PhD, head of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, at Ulm University Medical Center in Germany. “It’s not an antibody. It’s not an autoimmune antibody. It’s a naturally occurring protein working as antagonist when you treat the patient with wild-type leptin, then you will see that it’s blocking the receptor. And that’s what we saw also in the patients.”

I hope you enjoy this issue with a special focus on adolescent obesity. It’s such an important issue that can be addressed in so many cases that will not only improve the current and future health of these kids but take the strain off of the healthcare systems around the world. Just wish my mom was here to say, “I told you so!”