While certain thyroid cancer patients who have very small nodules well-located within the thyroid can be counseled rather than operated on, other patients might fare better undergoing surgery. At ENDO 2022, experts weigh in and debate when to operate and when to watch in patients with low-risk thyroid cancer in the session “Endocrine Debate: Low Risk Thyroid Cancer.”

Observation vs. intervention: A movement for less intervention has gained momentum in many forms of cancer when the disease is indolent and the patient’s risk appears low.

Low-risk thyroid cancer is no exception — and a session at ENDO 2022 will explore the issues involved in deciding between surgery and observation in what both participants promise will be a lively debate on today’s state-of-the-art.

The debaters will be Julie Ann Sosa, MD, MA, professor and chair of the Department of Surgery at the University of California San Francisco, and R. Michael Tuttle, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Endocrinology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Both served on the committee that wrote the 2015 American Thyroid Association guidelines on the management of adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Sosa is co-chairing the committee that is in the process of updating the guidelines for differentiated thyroid cancer.

- American Thyroid Association guidelines allow observation rather than surgery in properly selected low-risk thyroid cancer patients.

- Certain patients who have very small nodules well-located within the thyroid can be counseled on the possibility of opting for observation rather than surgery.

- Patients given the pros and cons can make very different decisions based on their perception of the risks of each path.

Both point to the 2015 guidelines as the basis for their approach. Sosa says that the guidelines “opened the door a crack to do active surveillance on tiny tumors” of less than a centimeter. The question is, how big is this crack. “Surgery — thyroid lobectomy — should remain the prevailing treatment, and that is what the guidelines say,” she notes.

Tuttle says that “the team that wrote the section on thyroid nodules said, if it looks like papillary cancer on the ultrasound, and it is less than a centimeter, you don’t have to biopsy it. We were trying to decrease overdiagnosis.” And if it didn’t need to be biopsied, it obviously didn’t need to be removed. “At that time there was emerging data that this was safe,” Tuttle says, and since then, the data has only gotten stronger on the viability of this approach in carefully selected patients.

Tumor Size and Location

Tuttle says that the first issues in considering a patient for observation are the characteristics of the tumor: “How big is it? Where is it located in the thyroid? Has it spread outside the thyroid?” Good candidates for observation are nodules “less than about a centimeter and a half, ideally less than a centimeter,” that are not on the edge of the thyroid where any growth could impinge on the windpipe or larynx, and that have not spread to a lymph node.

He says that an important part of the diagnostic process is communicating clearly with a good ultrasonographer “to ensure that they understand the key ultrasonographic findings that you need to know in order to determine if a nodule is ideal, appropriate, or inappropriate for active surveillance. This includes not only the largest diameter of the nodule but also a description of the position of the nodule within the thyroid, proximity to the thyroid capsule, evidence of invasion into the capsule, possible multifocality, and any suspicious cervical lymph nodes.”

“Many patients who could watch choose surgery. They want that cancer out of their body, so they are willing to accept the few risks associated with thyroid surgery. But it is also important for patients that choose surgery to understand that there is no guarantee that they will be cured with surgery.”

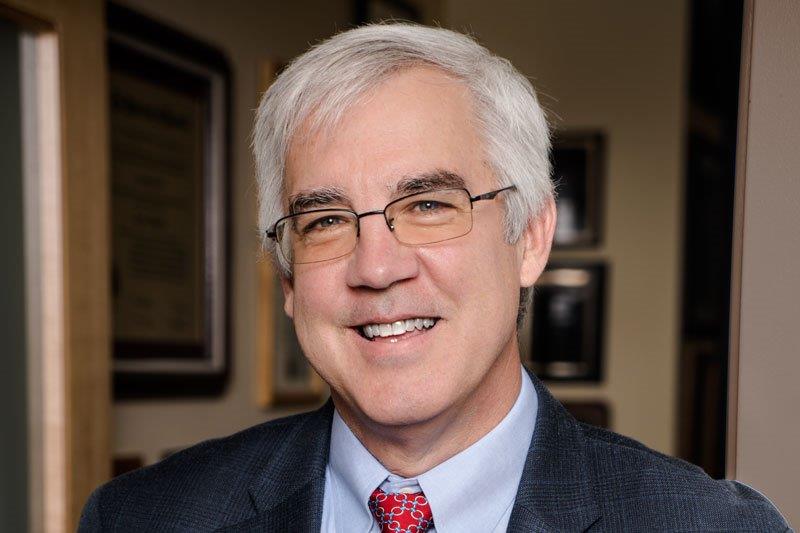

R. Michael Tuttle, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Endocrinology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, N.Y.

Age and Health

Another key set of considerations are the patient’s age and health status. Sosa would not recommend surgery for “an 85-year-old patient with a 1-centimeter papillary thyroid cancer who has high blood pressure and diabetes. But for a patient who is 20 years old who has a 1-centimeter papillary thyroid cancer, who is perfectly healthy, why not do the surgery that cures the patient and allows the patient to move on? Does it make sense to watch that patient for decades? That is probably not cost-effective, and young patients tend to have more progressive disease.”

Transferrable Data?

Sosa says that question is at evidential equipoise, with more data needed on the long-term outcomes of observation. The initial data on observation were just emerging at the time of the guidelines, with the best data coming from a group led by Yasuhiro Ito in Japan, but those data are not necessarily transferrable to the U.S. “We need to get more data to support active surveillance, and data from the U.S. not just Japan. The healthcare system in the U.S. is not the same as Japan,” Sosa says.

Tuttle counters that since the last guideline was written “there have been many more publications that show that the Japanese data is correct that observation is safe. Their findings have now been reproduced in multiple countries around the world.”

Careful Observation

For the patients who choose to go with observation, Tuttle prescribes an ultrasound every six months for the first two years along with a yearly TSH test. If the tumor hasn’t grown after two years, the ultrasounds can be done yearly. After five years, the ultrasounds can be spaced out to every other year.

“If the nodule gets bigger by more than 3 millimeters — because anything less than 3 millimeters is measurement variation that may not reflect a true increase in size — or if the volume grows by more than 75% – 100%, we can be confident the nodule is growing and should be considered for therapeutic intervention. Likewise, if the nodule is sitting on the edge of the thyroid and looks like it is starting to grow into the thyroid capsule, or if we identify metastatic thyroid cancer in cervical lymph nodes, that would take us to surgery,” Tuttle says. He says that the safety of waiting and operating if a tumor begins to grow has been documented by many studies.

Sosa says that there are many nonmedical factors — being uninsured or underinsured, or a low socioeconomic or difficult job status — that can make the follow-up process impractical for many patients. “I have had patients who live in a rural community in poverty, who manage to get to a physician for consultation and say, ‘It took everything for me to get here. I cannot come back.’ That patient can’t be followed. They cannot return every six months for tests. They should have surgery,” Sosa says. Observation also puts a huge compliance requirement on the patient.

“You talk to the patient. You discuss the risks and benefits of different approaches and see what risk they are willing to accept for the benefit. The patient is always queen or king. The patient should hear the arguments, and then make the right decision for them.”

Julie Ann Sosa, MD, MA, professor and chair of the Department of Surgery, University of California San Francisco

The Patient Is Queen

But Sosa and Tuttle agree that the most important considerations are the patient’s attitude and tolerance for risk. “You talk to the patient,” Sosa says. “You discuss the risks and benefits of different approaches and see what risk they are willing to accept for the benefit. The patient is always queen or king. The patient should hear the arguments, and then make the right decision for them.”

“In the patient that is ideal or appropriate for observation based on ultrasonographic criteria and medical team characteristics, I tell them that there are two right answers, observation or surgery,” Tuttle says. “And then they always tell me they only have one right answer. The ones that want to watch have to accept the risk that it might grow. They have to accept the unknown and that we are going to be doing ultrasounds for a long time. Many patients who could watch choose surgery. They want that cancer out of their body, so they are willing to accept the few risks associated with thyroid surgery. But it is also important for patients that choose surgery to understand that there is no guarantee that they will be cured with surgery. They will still need ongoing oncologic follow-up since even after appropriate surgical intervention, the risk of recurrence in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma ranges from 2% to 6%.”

Seaborg is a freelance writer based in Charlottesville, Va. In the March issue, he wrote about cortisol excess and whether it was safe regardless of the level.