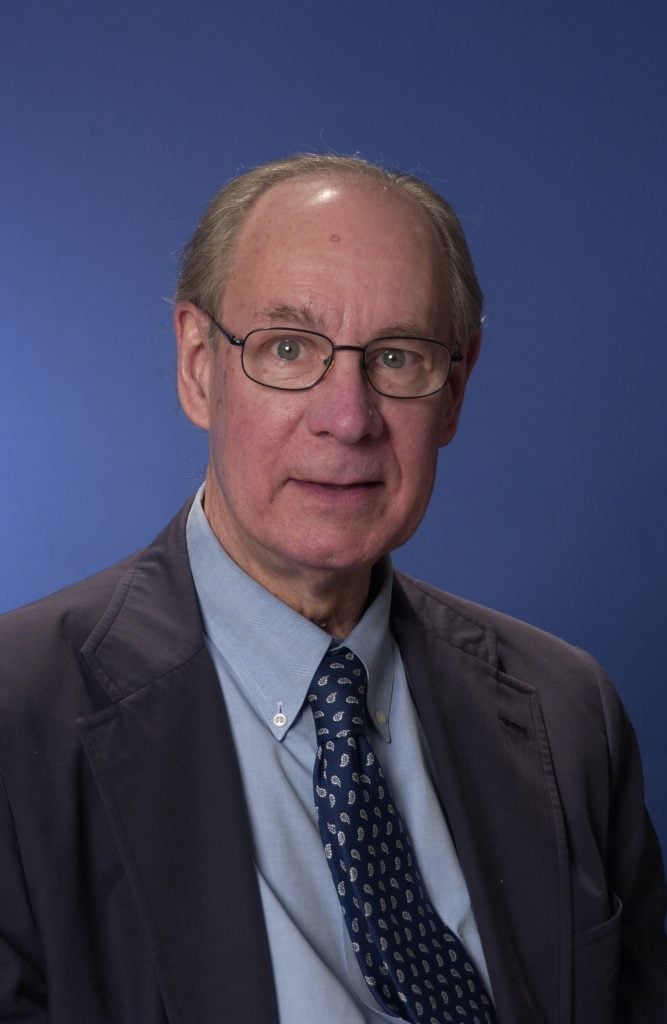

Endocrine News speaks with Joel Habener, MA, MD, the Endocrine Society’s 2018 Outstanding Mentor Laureate Award recipient, on how to help your staff make a good first impression with a few tips on writing a letter of recommendation.

[Editor’s Note: We are bumping up this 2021 interview with Joel Habener, MD, MD, who spoke to us about the best practices on writing staff recommendation letters.]

Grad schools, fellowship applications, and potential employers all depend on recommendation letters to help reveal applicants’ best accomplishments and strengths. As a lab manager or senior-level faculty member, odds are high that you have been asked to author such a letter for students or young employees advancing to the next stages of their careers.

Writing recommendation letters are a familiar process. Good letters are specific and include facts and anecdotes whenever possible. For instance, share whether the applicant has any unusual competence, talent, or leadership skills. What excites this person? What do remember most about him or her?

As the Endocrine Society’s 2018 Outstanding Mentor Laureate Award winner, Joel Habener, MA, MD, has written more than his fair share of recommendation letters in his position as the chief of Laboratory of Molecular Endocrinology at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at the Harvard Medical School in Boston. Endocrine News caught up with him to share his best advice for others who get the “ask.”

Endocrine News: Do you follow any set guidelines when asked to write a recommendation letter?

Habener: The guidelines I follow are: 1) Determine when the recommendation is required by the requestor;2) Place the preparation of the recommendation at the top of the list of things to do. Remember that letters are extremely important for the career development of the individual requesting the recommendation; 3) Focus on the positive aspects of the experience with the individual, such as accomplishments, effort, personality, and relationship with peers. Invite the recipient of the letter to phone with requests for additional information, meaning information that would be considered negative, such as problems with performance, behavior, or interpersonal relations. This keeps the negative information “off the record.”

EN: Is it OK to ask the requesters to write what information they want the recommender to include?

Habener: Absolutely. It is helpful, if not essential, to sit down with the requestor and obtain a good understanding of the purpose of the letter and if there is specific information that is requested. In reality, many recommendation letters are forms requesting numerical evaluations of certain criteria relating to the individual, followed by a section for inserting comments.

EN: Is there a best way to decline writing a recommendation?

Habener: That is an interesting question. I don’t recall ever declining writing a recommendation. I imagine that such would occur under two circumstances. First, if I did not have sufficient information about the requestor, such as a very limited contact, relationship, or experience, and second, if the relationship/experience was not a good one.

“Invite the recipient of the letter to phone with requests for additional information, meaning information that would be considered negative, such as problems with performance, behavior, or interpersonal relations. This keeps the negative information ‘off the record.’” – Joel Habener, MA, MD, chief, Laboratory of Molecular Endocrinology, Massachusetts General Hospital; professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.

In the former instance, I would prepare a brief letter documenting the nature of the experience, the time spent, and that objectives were met.

EN: Do you often hear from the requester about the outcome of their application?

Habener: Yes, and by “often” I would say maybe 75% of the time I receive a thank you and an update of the outcome. Most of the letters I have written have been for trainees who are moving up to the next step in their career ladder, such as an application to medical school, a graduate program, or to a junior faculty position. The letters precede their leaving the lab so we can keep informed on the progress of the applications. My last research student was accepted to all five medical schools he applied to, requiring an additional request for advice from me.

—Fauntleroy Shaw is a freelance writer based in Carmel, IN. She is a regular contributor to Endocrine News.