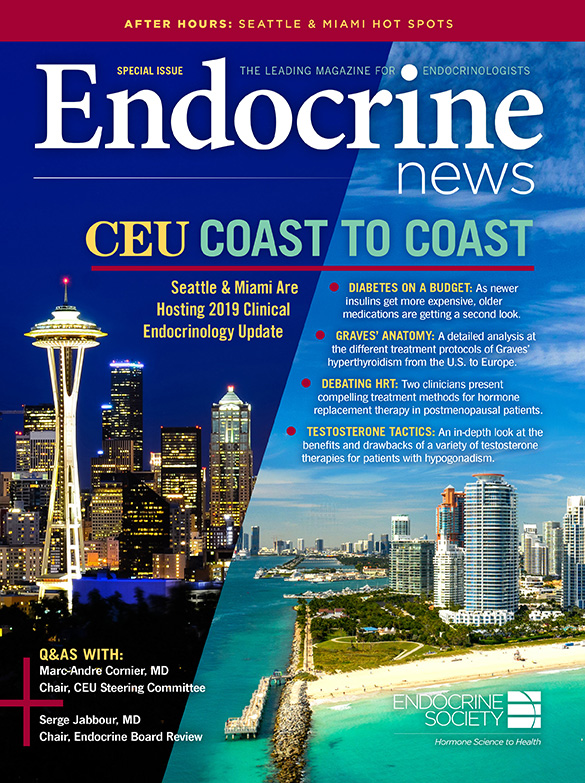

Disagreements abound in treating Graves’ hyperthyroidism from the U.S. to Europe as different treatment protocols take precedence. In both Seattle and Miami, “Diagnosis and Management of Graves’ Hyperthyroidism” will demonstrate these conflicting practices and the progress that has been achieved.

Graves’ disease – the most common cause of hyperthyroidism – affects between 1% and 1.5% of the population, occurring in women and African Americans the most, and hitting iodine-replete regions of the world especially hard, with 20 to 30 cases per 100,000 people each year. If left untreated, hyperthyroidism can lead to myriad complications, from osteoporosis to cardiovascular problems.

Graves’ disease, of course, has no cure, but recent years have seen many scientific advances in its management, which meant the medical community had to rise to meet the challenge of what to make of all the new developments, and yet some transatlantic disagreement remains.

In 2016, the American Thyroid Association published its updated guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease, which included 124 recommendations to help physicians in the optimal practice of treating patients, including management of Graves’ hyperthyroidism using radioactive iodine, antithyroid drugs, and surgery.

“With personalized medicine, the physician informs and councils the patient, and answers all questions pertaining to the several treatment approaches.” – George J. Kahaly, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and endocrinology/metabolism, chief physician, Endocrine Outpatient Clinic, Johannes Gutenberg University (JGU) Medical Center, Mainz, Germany

Two years later, the European Thyroid Association published their own guidelines on this topic, and lead author George J. Kahaly, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and endocrinology/metabolism and chief physician of the Endocrine Outpatient Clinic at the Johannes Gutenberg University (JGU) Medical Center in Mainz, Germany, says that there is a bit of a distinction between the American and the European guidelines when it comes to how clinicians should approach caring for these patients.

Kahaly is the director of the Molecular Thyroid Research Laboratory at JGU and has authored 257 original papers and reviews, covering clinical and experimental aspects of endocrine autoimmunity, immunogenetics of thyroid and polyglandular autoimmunity, as well as cardiovascular involvement of metabolic disorders. He is an associate editor of The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism and on the editorial board of the European Thyroid Journal, the official journal of the European Thyroid Association.

In the session “Diagnosis and Management of Graves’ Hyperthyroidism,” Kahaly brings his expertise to CEU 2019. “I will show the main differences between Europe and the United States, between the European guideline and American guideline,” he says, “telling the audience, why are we choosing in Europe medical treatment first? What are our arguments? Why should we go first for the conservative management? Then, if we are not successful, go for definitive or ablation treatment, i.e. surgery or radioactive iodine.”

U.S. Versus Europe

Kahaly and his team at JGU Medical Center follow one thousand patients a year with Graves’ disease and/or autoimmune thyroid disease, experience that he says informed how he and his co-authors drafted the European guidelines. While Kahaly worked on the draft of the European guidelines, he spent time talking to Douglas Ross, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, who is the lead author of the American guidelines. “We had the opportunity to compare the two guidelines and to discuss actually the management for the patient with Graves’ hyperthyroidism in the United States and in Europe,” Kahaly says.

“In these last three years we have observed a tremendous progress in the management of Graves’ hyperthyroidism, as well in the management of Graves’ eye disease. I will make it clear to the audience and show them the progress achieved. And I will offer the audience a perspective for the next five years, how are we moving and where are we moving in those diseases.” – George J. Kahaly, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and endocrinology/metabolism, chief physician, Endocrine Outpatient Clinic, Johannes Gutenberg University (JGU) Medical Center, Mainz, Germany

In 2016, Kahaly and Ross shared the stage at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association in Denver, debating how to treat patients with Graves’ hyperthyroidism. The European guidelines call for a more conservative treatment, using antithyroid drugs (ATDs) like methimazole as the first-line, long-term treatment, while Kahaly says that for years the primary treatment of Graves’ hyperthyroidism in the US was radioactive iodine (RAI).

Indeed, the 2016 American guidelines acknowledges this discrepancy, with the authors writing, “In the United States, RAI has been the therapy most preferred by physicians, but a trend has been present in recent years to increase use of ATDs and reduce the use of RAI. A 2011 survey of clinical endocrinologists showed that 59.7% of respondents from the United States selected RAI as primary therapy for an uncomplicated case of GD, compared with 69% in a similar survey performed 20 years earlier. In Europe, Latin America, and Japan, there has been a greater physician preference for ATDs.”

The European authors in their recommendations describe in detail the pros and cons of the three currently available treatments for autoimmune hyperthyroidism. Pertaining to RAI, which results in both decreased thyroid function and reduction in thyroid size, the European guidelines state the following: “There are neither good measures of individual radio sensitivity nor ideal methods of predicting the clinical response to RAI therapy.”

“At the ATA annual meeting in Denver, September 2016, I reported on the long-term experience with the conservative ATD treatment,” Kahaly says, “arguing for this treatment and demonstrating that you are not harming these patients. Furthermore, you may offer these subjects a long-term treatment if they are compliant and tolerating the drug. Overall, the discussion in Denver was lively, illuminating and very informative, offering the audience a complete state of the art of the management of Graves’ disease in the U.S. as well as abroad.”

Personalized Medical Approach

For Kahaly, this more conservative approach to treating patients with Graves’ hyperthyroidism is an important aspect of personalized care, in which the physician can lay all the options out of the table and recommend a relative harmless, non-invasive route. “With personalized medicine, the physician informs and councils the patient, and answers all questions pertaining to the several treatment approaches,” he says.

He hopes to do the same with the CEU attendees, informing audience members about the strides the endocrine community has made in treating patients with Graves’ disease and the steps needed to keep moving forward. In fact, Kahaly will be busy at CEU, giving both the plenary talk on Graves’ hyperthyroidism as well as a meet-the-professor lecture on Graves’ eye disease. Subsequently, he will join a roundtable discussion on thyroid function tests.

“This is the second time I’ve been invited to the Clinical Endocrinology Update, the last time in 2016,” he says. “And in these last three years we have observed a tremendous progress in the management of Graves’ hyperthyroidism and associated eye disease. I will make it clear to the audience and show them the progress achieved. In addition, I will offer the audience a perspective for the next five years, how and where are we going from now on. The progress will be challenging, both in Europe and in the United States.”

-Bagley is the senior editor of Endocrine News. He wrote about treating infants born with differences in sex development in the July issue.

REGISTER TODAY FOR CEU IN MIAMI OR SEATTLE!

Diagnosis and Management of Graves’ Hyperthyroidism

Miami

Saturday September 7, 2019, 11:20 – 11:50 AM

Seattle

Saturday September 21, 2019, 11:20 – 11:50 AM