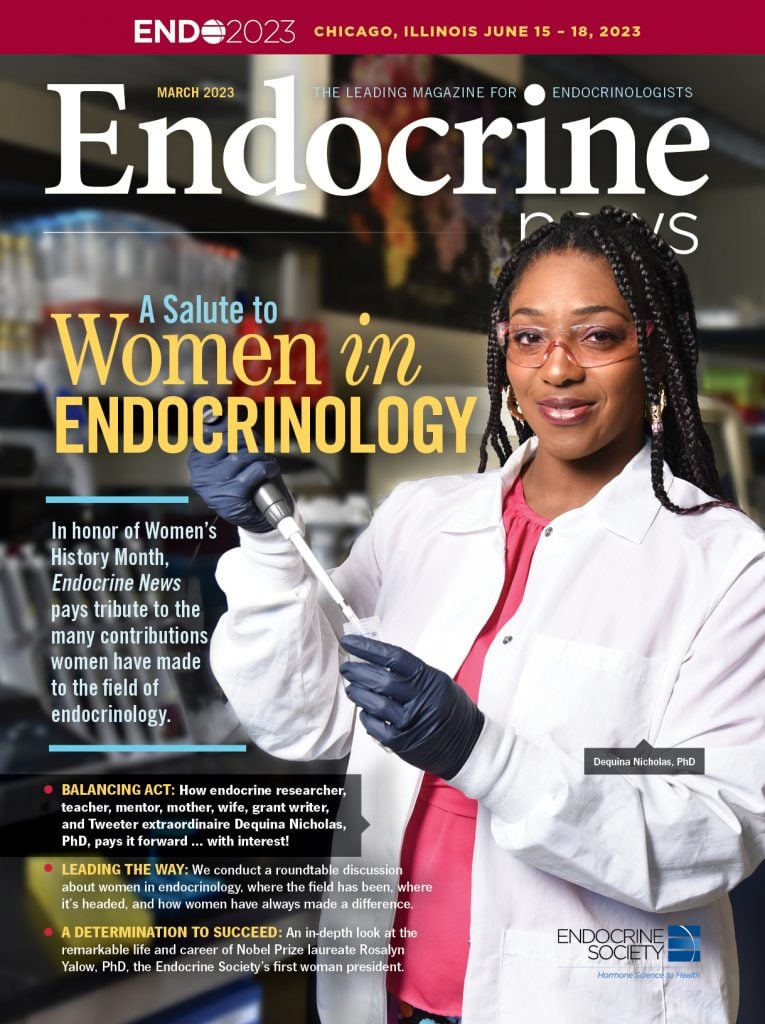

Dequina Nicholas, PhD, is an assistant professor at UC Irvine. And a PI in her own laboratory studying PCOS, diabetes, and various women’s health issues. She’s a teacher, mentor, and motivator. She’s a wife and the mom of a toddler. When she’s not writing grants, she’s on hikes with the members of the Nicholas Lab. And she Tweets! She squeezed talking to Endocrine News into her unrelenting schedule to tell us not just how she does it, but why she does it.

Can women in the world of endocrinology research have it all? Can they lead a successful lab, earn top funding awards, and start a family early in their careers? In her everyday life, Dequina Nicholas, PhD, shows that, unequivocally yes, all of it is definitely possible. But it wasn’t until Nicholas met a mentor who was managing it all that she really believed it was possible for her, too.

Nicholas is an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at the University of California, Irvine, who became the principal investigator of her lab in 2021. After graduating magna cum laude from Southern Adventist University in 2009, she earned her PhD in Biochemistry from Loma Linda University, followed by two postdoctoral fellowships.

At UC Irvine, the Nicholas Lab buzzes with 19 team members who work towards the goal of improving diabetes care by unlocking the mysteries of the impact of immune cells on metabolism and reproduction. In 2022, Nicholas’ work was recognized with the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In between long research hours in the lab, Nicholas works to change the culture of lab collaboration. Her Twitter account reads like a 101 course on surviving not only being a young PI, but also a scientist of color. It’s everything from tips on how to manage time and submitting R01 grants (“#grantwriting”) to the joys of making the broccoli dinner requested by her 2-year-old daughter.

Endocrine News spoke with Nicholas about how she successfully juggles multiple roles and embraces her culture all while mentoring everyone who needs it under a basic life creed: pay it forward…with interest.

Endocrine News: Let’s back up a bit before your educational career and talk about how you landed here. I read that your mother struggled with type 2 diabetes and that sparked your interest in the disease. Is that when you knew science or research would be your career path?

Nicholas: First, to set everything up, my hometown is Pensacola, Fla., but both my parents are immigrants. My dad came here from Dominica, and my mom’s from Jamaica. They didn’t really have any idea how the higher education system worked in the U.S., but culturally they very much value education. So, the message was you’ve got to get an education. That’s how you get ahead in life and that’s why we moved to the United States.

I was a chemistry major in undergrad, but I still had no clue what I wanted to do, but I’m super ambitious. So, I went through the honors program, and as part of the honors program you have to do research. I was basically working with acids and alcohols and found the topic incredibly boring. I didn’t enjoy the topic I was researching but thought the process of research was amazing. I fell in love with it.

I want to win a Nobel Prize, to be the first Black woman in medicine to win a Nobel Prize and then change the minds of people so that when they think ‘scientist,’ it’s not a surprise to them that a Black woman is a scientist. I need it to be the norm that scientists can look any type of way.

But I still didn’t know what I was going to do with my life. Everybody said, obviously you can go to medical school because every single child of an immigrant parent is supposed to go to medical school, you know the American dream. So once again, I got a little bit of experience. I shadowed in an emergency room, and it was cold, all the walls were white, and everybody’s sick. I can’t do this. Medicine was not for me, but once again, I still loved science. Long story short, my mom’s friend’s brother happened to be a professor at Loma Linda University. This is a small, private institution that doesn’t have a very large research program but they’re pretty well resourced. So, my parents had me talk to him and he asked me if I was interested in research, and he told me I could do research as a career. I told him that I did research in undergrad, and it was fun and I loved that I could make my own schedule.

He said if I wanted to do research as a career, I had to get a PhD and I didn’t know what that was either. He told me to take the GRE and put in an application that was due in two months. So, I signed up for the next GRE, didn’t do great, but I did well enough to get into the program, and that was the only program I applied to. I was not the most competitive applicant, but God made a way. So that’s how I got into graduate school.

In graduate school they told us you have to rotate through labs and figure out what it is you want to research. I knew what I cared about. My mom has diabetes. My grandma has diabetes. I know it’s coming for me, and I wanted to understand how it works. So, eventually I rotated through a lab that was studying diabetes and I knew I wanted to land there. Little did I know that there are two types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2. I had no idea there were two different kinds. And you can see that through my whole journey, there’s just a lot of naivety. I learned as I was going, and this is part of the struggle for any first-generation scholar. As I’ve gone through my entire journey, my heart has really gone out to those who are trying to navigate this and don’t have anyone to tell them what to expect next or even how to be a competitive applicant.

It seems like almost every step in my career I had to figure out stuff after everyone else did, and I hated that feeling. How does everyone else around me know what’s going on but me?

EN: You call it naivety, but I think it’s just not having doors open for you that many other people do, especially students of color. Luckily you made some great connections like your mother’s friend at Loma Linda. Can you talk about what other mentors you’ve had, people who were really important to your educational career or help guiding you, and why is it important for you to return the favor to young researchers or students coming behind you.

Nicholas: Every step of my career I’ve had people who have poured into me, who have gone out of their way to make sure that I am supported and that I am successful, and this is a little different for every mentor I’ve had. My grad student mentor at Loma Linda was Dr. William Langridge. Our relationship didn’t start out close, but by the time I was graduating, he was supporting me in more than just my science. I can work hard, right, but then life happens. Dr. Langridge came to my dance recitals because I was doing salsa dancing in grad school. When I had a really bad breakup, I sat in his office and cried. He hugged me and said ‘you are going to get through this. You are going to be okay.’ He even helped my boyfriend, now my husband, set up a Valentine’s surprise for me in the lab. It was little things, but he saw me as a whole person and not just as somebody doing research in the lab.

EN: That type of support is so important.

Nicholas: Yes, it is. And another one of my mentors at Loma Linda, and this really does attest to why I think it’s important to see the student and not just see the work that they’re producing. Her name is Dr. Kimberly Payne. She’s one of my late mentors and I owe her so much. There was a time in grad school where I was going through food insecurity. She noticed that I would come to lunch with my friends, but I wasn’t eating anything. Dr. Payne noticed and thought “this is not like Dequina, why is she not eating?” Because she knew I liked to cook and always had food, but at that time in my life, I basically had to choose between paying my rent or buying groceries.

Dr. Payne started coming to me saying “Dequina, I accidentally left this extra food in the freezer. You can have it if you want.” So, when she noticed I was eating the food, she knew something was going on with me. She took me aside and set me up with a food pantry. Essentially, I would just get bags of groceries every other week and I was so very grateful for her supporting me. Not embarrassing me or outing me to anybody else because I couldn’t afford to buy food.

EN: And she did something for you that you may have never done for yourself. But she noticed a change and helped you privately. That is really huge.

Nicholas: It is. A third mentor, Dr. Mark Lawson, really taught me how to have fun and prioritize people over products. So those three mentors have done a lot in shaping how I mentor my students now. I let them know when we first start that in my lab, we are hyper-familiar and if you’re uncomfortable with that let us know. I want to know about you as a person and you will know about me as a person. I will share stuff about my family life. They know about my husband and my kid. I know about them. If something happens, we want to be able to support each other. This lab, our community, is a safe space. I’ve had those safe spaces and I need my students and mentees to have that same type of safe space.

Another one of my favorite mentors is Dr. Barb Nikolazyk. Once I got into grad school, you very quickly notice when you’re the only. You go to a conference, and you feel like you don’t belong. And I had decided from a young age that I wanted a family, but the messaging was very clear that you can’t have a family, be a good mom, and also be an awesome scientist. The messaging was very scary. Even simple stuff like, if I change my last name what does that do to my career? And I realized these are big issues that I needed to face, and I really wanted a mentor who understood these issues. I would look and didn’t see these women. Where are the women who are top of their field, getting top grant money, all the while raising kids and enjoying their lives?

So, I met Barb because Dr. Payne made the connection. She asked me to pick Barb up from the airport when she was coming to my school to give a talk. So, I picked Barb up from the airport, and the first thing she says when she gets in the car, “Hi, Dr. Payne said a lot of great things about you. I can’t wait to go to the Grand Canyon with my kids.” She had planned to do all these fun family things and it was blowing my mind because I knew her from her work. I knew her papers. I knew where she was in the field, and I’m thinking this is exactly the type of mentor who I want in my career and in my life.

I later did my postdoc in her lab at Boston University, and she lived up to all my expectations. She made a point to show me the politics behind the job. How faculty talk to each other, and what is going on behind the scenes. Basically, she wanted me to never be disillusioned with the career path that I had chosen, and I loved that. So once again, I’m now very transparent with my own students, too. I want them to know these are things to talk about at faculty meetings. This is how politics works around you. Not so that they’re a burden but that they understand this is the environment we are in.

Barb is the one who helped me build my self-confidence. Because you have all different intersectionalities, right. I’m a woman in science. I’m Black. So, you have to navigate all of those things and now I’m a mom in science, but I saw how she did it, how she coped with it. I can ask her questions about it. She is unapologetically herself.

That was eye-opening to me because I was a little bit careful about how much of my Blackness to share. How much of myself do I share? I want to be my authentic self in any space where I am. When I went on the job market interviewing, it was so much easier after having had her mentorship and guidance to know I wanted to work at an institution that accepts me for who I am. I don’t want to be in a place where I feel like I must pretend to be somebody else.

EN: And UC Irvine gives you that?

Nicholas: Irvine gives me that 100%. I came here to interview, and the faculty made me feel like a colleague. Made me feel like my opinion matters and they still do that to this day. Everything they say about DEI, for instance, they back up with actions. Of course, improvement is slow because it’s academia; everything is slow in academia. But everyone is trying, and people actually care.

EN: I love that your Twitter bio says “scientist” and “don’t be surprised.” Tell me what you mean by that.

Nicholas: I think very long term. My long-term goal is by the time I’m 50-whatever, I would have had a long career in science. I want to win a Nobel Prize, to be the first Black woman in medicine to win a Nobel Prize and then change the minds of people so that when they think ‘scientist,’ it’s not a surprise to them that a Black woman is a scientist. I need it to be the norm that scientists can look any type of way. Part of the issue is Hollywood, but also historically all the people who have been credited with all the big discoveries in science, have always been white men.

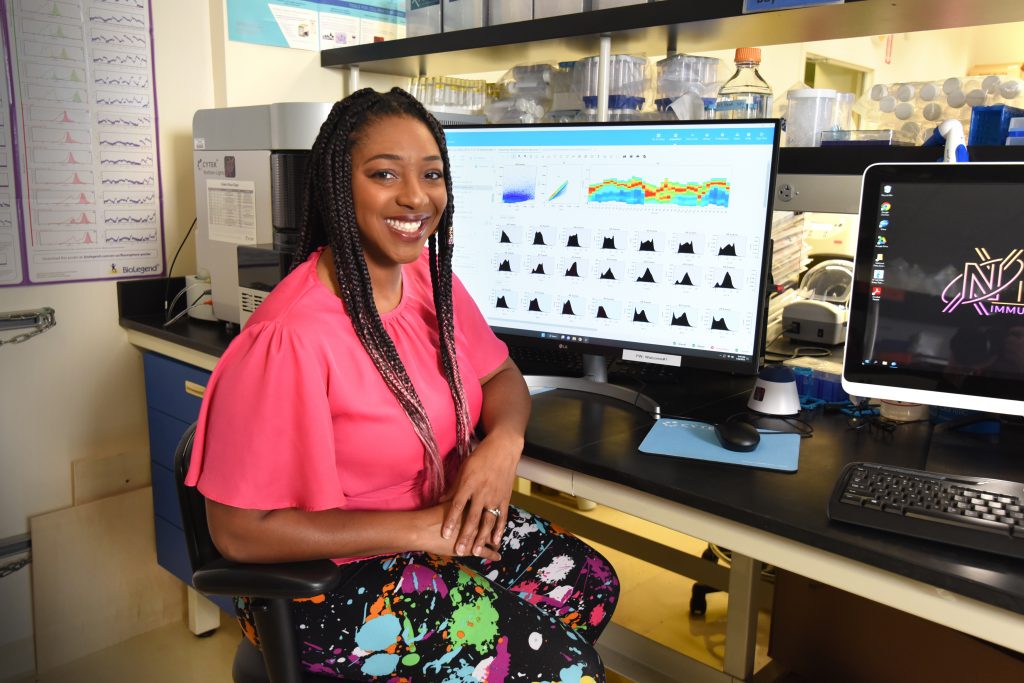

[Photo: UCI School of Biological Sciences]

As a society, we must change minds and show that everyone can do science. And do it well. This is why I am going to climb to the top. The person on the top has the power to enact that change so I’ve got to get to the top as fast as I can. That’s the goal.

EN: Let’s talk about the Nicholas Lab. The magazine has interviewed many young investigators who are leading their first lab and they talk about the challenges of getting started after the funding grant is approved. That often there’s not much support for learning how to hire a team, or order supplies. How have you navigated these challenges? What stands out as the first couple of things that you had to overcome as a new PI?

Nicholas: So that is a very interesting question because by the time I had gotten this position, I have been wanting this for so long, I already knew what I wanted to do. I had plans outlined. I very much became an over-planner, maybe to compensate for me always feeling like I was behind everybody else.

First of all, I picked an institution that gave junior investigators a lot of support. Before even coming on this campus, I had administrative support who explained how to order supplies, how I hire staff, how to do human resources. So, I don’t feel like I ran into any substantial challenges that I hadn’t planned for already.

I guess what I couldn’t have anticipated is that feeling of you’re not good enough when you first start. The fear of going from having mentors to running things by to, no, I’m it. I’m in charge. It took me a couple of months to recognize that all my training, everything I’ve done, has prepared me for what I’m undertaking right now.

One story: there were a couple new PIs and they were trying to figure out how to get blood samples. I told them we’re going to have a 30-minute meeting and I’m going walk you through every single step. This way it takes them 10 minutes instead of a couple of days with a whole bunch of email chains to figure it out. I want to stop the mentality of ‘I figured it out, so you need to figure it out, too.’ I want the thinking to be ‘I figured it out, so let’s make it easier for the next person.’

EN: I hope anyone who reads this and who is in your position will be motivated by that thinking, that they might think, ‘I could do that on my campus.’

Nicholas: It’s like every single person who’s ever helped you, pay it forward and then some. Pay it forward with interest.

EN: Can you talk about your investigations and what are your five-year or 10-year research goals?

Nicholas: My research actually divides into two sides that are interconnected. We basically study chronic inflammation and endocrine disease. One endocrine disease is type 2 diabetes, and you know from my background why I want to study diabetes. Another endocrine disease is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). In general, women’s health and these diseases are understudied and PCOS is one of those.

As a society, we must change minds and show that everyone can do science. And do it well. This is why I am going to climb to the top. The person on the top has the power to enact that change so I’ve got to get to the top as fast as I can.

So much money has been poured into understanding diabetes, how it’s occurring, treatment, etcetera, all stuff like that, especially type 2 and it affects so many people. There’s chronic inflammation associated with diabetes. We believe this is upstream of insulin resistance. In mice, we can cure diabetes over and over again. It’s great. Scientists curing mouse diabetes. But this inflammation that we see in humans, we know it’s different from mice and we have no idea what’s causing it. I was recently funded with a Director’s Innovator Award, to basically investigate what are the causes of the inflammation. Our lab proposes that there’s lipid-specific interactions of the immune system that can drive insulin resistance.

So, our goal or my goal over the next five years is to lay a foundation for, first of all, the ability of the human immune system to recognize lipids and what these outcomes look like in human health. And then also how this can be a driver of type 2 diabetes. Then beyond that understanding I want to allow us to develop immunotherapies that actually help reduce blood sugar, actually help neuropathies, help get this inflammation that we see chronically in people under control.

So, on the other side of my lab we study PCOS. Interestingly, we discovered a whole bunch of immune cells in the pituitary, and we know that if you get rid of these immune cells in mice then you dysregulate reproductive hormones. So, our whole goal is to understand how the immune system is interacting with hormone production. Hopefully with more understanding we can use this to develop immunotherapies for PCOS.

EN: You’re just not a scientist. You’re a motivator, teacher, and mentor. How do you do it all? How do you do your research, care for a toddler at home, and have family life? And Tweet!

Nicholas: I get asked this question a lot. Of course, there’s give and take amongst things. I do a lot and I juggle a lot, so you do have to prioritize. You must be very organized and work efficiently. So, if I’m up late at night writing a grant and the words are coming slowly, I stop and get some sleep. I think I’ll do it later when I can get a lot of words written down. I also have dedicated space and time when I normally Tweet to maintain a social media presence. I queue the tweets at night when I’m lying down with the baby because I can’t do anything else and then usually around 9 a.m., in transit, I’ll shoot off the tweet. If I’m walking to a meeting across campus, that’s five minutes when I can shoot off a tweet of something that happened during the day. So, I’m not sitting down taking 10 minutes of my precious time and crafting tweets. That’s not efficient.

I also use a lot of calendar blocking for the really, really important things. Then I provide myself with a lot of flexibility in my day. With that said, I’ve also learned to delegate and ask for help. That’s been one of the most important things for launching new endeavors. One of my students and I are trying to build an LLC called 1st Gen in Stem. So, we have the groundwork laid out for it. We’ve been writing a theme song that my cousin’s going to record. She’s a fabulous singer!

I want to stop the mentality of ‘I figured it out, so you need to figure it out, too.’ I want the thinking to be ‘I figured it out, so let’s make it easier for the next person.’

In general, I do have a very high capacity and part of it is that I get so much joy from my work. I love what I do. I would not trade it for anything in the world.

EN: Loving your work is key to keeping you moving. I saw you Tweeted a photo of you and your team going hiking. That’s showing that keeping that healthy balance is so important.

Nicholas: It really is. I love doing active things. I love that my lab team is social, and they talk to each other. We did renovations in the lab before I came in and I told the planners that I wanted open seating so students could sit in a way that makes them want to talk to each other. People may think if you’re not focusing and being quiet, that you’re not getting work done. Not true. I want my team to feel like they can talk and have a good time while doing their work.

Building those personal connections and relationships, it lets them know they can support each other, they can trust each other — not just with their personal lives but with the experiments they’re there to create. It’s about knowing the whole person.

—Fauntleroy Shaw is a freelance writer based in Carmel, Ind. She is a regular contributor to Endocrine News.

Read more about the work of the Nicholas Lab and follow Nicholas on Twitter @QuinaScience.