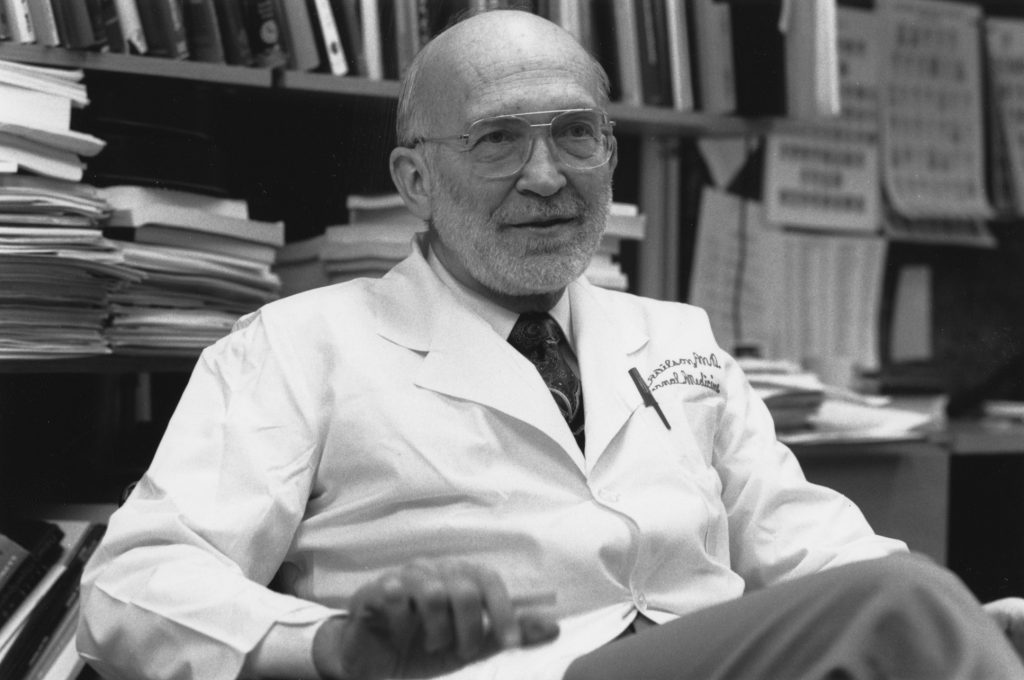

When Endocrine Society past-president Jean D. Wilson, MD, passed away in June, the sheer volume of accolades and anecdotes that came pouring in made it obvious that he had an enormous impact on the field of endocrinology. Stephen R. Hammes, MD, PhD, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, N.Y., and Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich., share their memories of this remarkable man and how he touched their lives and careers.

Jean Wilson, MD, past-president (1990-1991) of the Endocrine Society, the American Society for Clinical Investigation, and the Association of American Physicians, died peacefully on June 13 at the age of 88.

Raised in the small town of Wellington on the Texas panhandle, Jean went on to major in chemistry at the University of Texas (Austin). He then attended the fledgling medical school UT Southwestern in Dallas in Quonset huts and temporary buildings with the intention of becoming a medical missionary. After remaining for internal medicine training, he spent two years at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) before returning as a faculty member in 1960, where he remained for the next 60 years. His scientific contributions are best remembered for the discovery and characterization of the 5α-reductase enzymes, genes, and deficiency syndromes, which culminated in the development of specific inhibitors used clinically for prostate hyperplasia and hair loss.

While Jean Wilson’s basic and clinical investigation of androgen biosynthesis and action have profoundly influenced endocrinology, his contributions extend well beyond the laboratory. He cared for the indigent patients of Dallas for decades at Parkland Hospital, both on the inpatient medicine service and the endocrinology clinics. He educated and mentored scores of students, residents, fellows, and junior faculty. His scholarly presence at grand rounds and didactic conferences fostered critical thinking and high standards. His service to professional societies and journals has left a lasting impact on academic medicine.

Most of us remember Jean for his broad interests in the arts and natural sciences. He could tell you, from memory, the prevalence of cryptorchidism in pigs, the reproductive cycle of the platypus, or the reason why male Seabright-Bantam roosters have henny feathering. He was fascinated with birds and became an expert bird watcher, roaming the globe to fill his “bird life list.” After Don Seldin introduced him to opera, Jean became a lover of classical music and musical performances. He would visit Maria New in New York for a week to discuss cases by day, tour museums in the afternoon, and take in opera or a show at night. He was as comfortable discussing sixteenth century paintings as the molecular defects in androgen insensitivity – and he enthusiastically shared his love of art and science with his friends.

I remember being a first-year endocrinology fellow at the University of California San Francisco and sitting in the office of Marvin Siperstein, a giant in diabetes research and chief of endocrinology at the San Francisco VA hospital. Marvin was explaining to me the importance of strong physician-scientists in medicine. He regaled me with stories about the amazing Jean Wilson, who was a fellow in Marvin’s lab at UT Southwestern years before making his seminal discoveries regarding androgen metabolism and actions. Marvin could not say enough positive things about Jean’s scientific accomplishments and dedication toward medical research. Fast-forward three to four years later, and I found myself sitting in Jean Wilson’s office at UT Southwestern interviewing for a job. I was timidly describing to him my plans to do something radical. I was going to study the novel concept of extranuclear, or nongenomic, steroid hormone signaling — something that challenged one of the very things that Jean had discovered — that steroids signal by modulating transcription. Even more crazy — I was planning to study this in frog oocytes.

“My indelible image is still Jean standing in my kitchen with my two small children next to him, as he explained to them how his peanut butter maker worked, followed by the synthesis, not of steroids, but of delicious peanut butter for them to eat. That’s just Jean – above all else, he was a caring man who made everybody around him happy.” – Stephen R. Hammes, MD, PhD, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, N.Y.

I should have known better than to worry. Jean nearly jumped out of his seat and told me that my ideas were wonderful and that the use of a strong, alternative animal model system would be a tremendous asset. That was all I needed, and off to UT Southwestern I went! Little did I know that I would sit in that very office hundreds of times over the next 10 years, as Jean read and edited my papers, advised my research, discussed the previous evening’s symphony concert, or talked about the latest opera he saw in New York (in fact, Jean gave my wife and me his box seats to the opera in Dallas – the first of many operas that we attended in person). Jean’s passion for training physician-scientists bolstered my desire to try (but of course never completely succeed) to emulate him, leading me to become a fellowship director and mentor to physician-scientists.

I would not be where I am today without Jean Wilson, and I doubt a week will go by where I will not think of him. But it may not be remembrances of those days in his office, or the lively fellows’ conferences at UT, or the steroid synthetic pathways that he (and Rich Auchus!) taught me. My indelible image is still Jean standing in my kitchen with my two small children next to him, as he explained to them how his peanut butter maker worked, followed by the synthesis, not of steroids, but of delicious peanut butter for them to eat. That’s just Jean – above all else, he was a caring man who made everybody around him happy. – Stephen R. Hammes, MD, PhD

Jean loved to talk about anything — family, music, science, food. He listened and took an interest in not just my career, but also my life and my person. I could share results with him: results from an experiment or my time in a triathlon, and he would get just as excited. I guess that was the quality of Jean I admired most: He never became too famous or too old to revel in new knowledge, a new baby, new fellows, or seeing and hearing a bird, performance, or a piece of art for the first time.

“Jean knew how to make science truly an adventure…. I hope that we all learn that lesson from Jean, that a life in science is an adventure, not limited to research, and that we should all enjoy the ride, living every day immersed in the totality of experiences that makes us human.” – Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

Jean knew how to make science truly an adventure. The last major project of his career was to show that testosterone, not dihydrotestosterone, is the circulating androgen during male sexual differentiation. He traveled to Australia to work with wallabies as the best model in Marilyn Renfree’s group. He painstakingly performed difficult dissections and incubations himself. On return to Dallas, I watched him tediously run and then cut thin-layer chromatography strips, struggling to quantify multiple compounds, a nearly impossible task (“Jean, we have machines that do this better now, called HPLCs…”). His efforts allowed us to (re)discover the alternative or “backdoor” pathway to dihydrotestosterone — and the differences between humans and marsupials, with testosterone being important for the former not the latter! I hope that we all learn that lesson from Jean, that a life in science is an adventure, not limited to research, and that we should all enjoy the ride, living every day immersed in the totality of experiences that makes us human. – Richard J. Auchus, MD, PhD