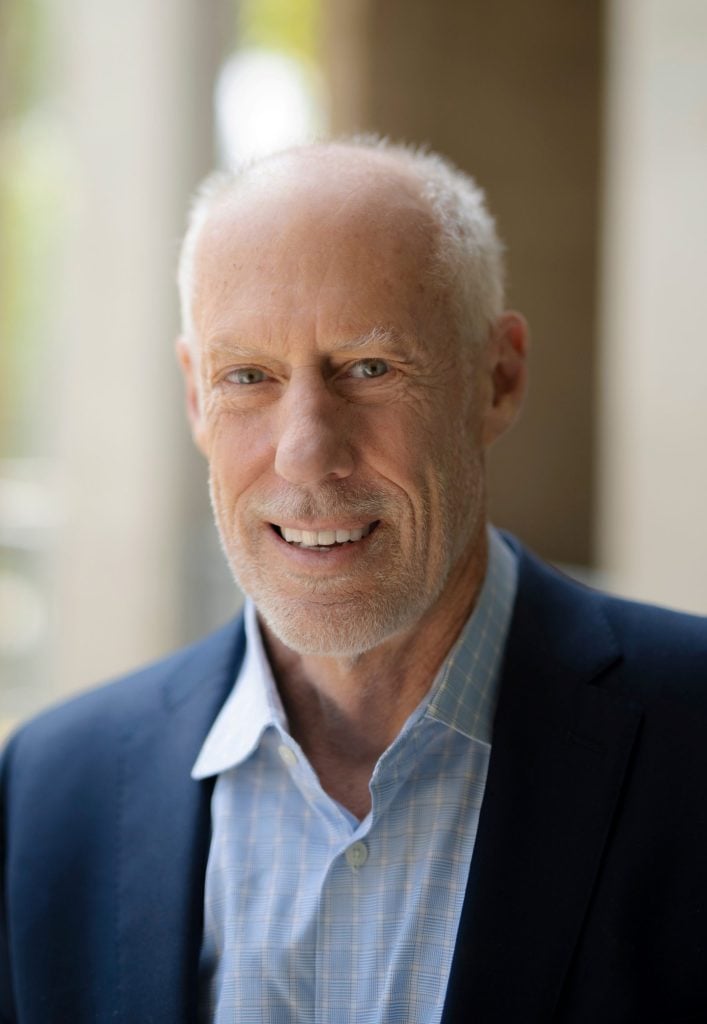

Recipient of the 2026 Edwin B. Astwood Award for Outstanding Research in Basic Science, Christopher Glass, MD, PhD, talks to Endocrine News about how endocrinology lured him away from cardiology so many years ago. He also discusses his lab’s macrophage research and what he tells his postdocs about “the intersection between three different facets of biomedical science.”

In sunny San Diego, Calif., where the ocean beckons nearly year-round, Christopher Glass, MD, PhD, starts his day with a morning swim, a ritual he says helps him “clear his brain” before heading into the lab. A former competitive swimmer, Glass credits the discipline and stamina from years in the pool with shaping his approach to research.

At the Glass Laboratory, he investigates how nuclear hormone receptors and other signal-dependent transcription factors control macrophages — immune cells that play critical roles in health and disease. His work has revealed new insights into how these cells develop and function, offering implications for nearly every chronic disease.

Glass’ contributions have earned his place among the Endocrine Society’s 12 distinguished leaders in endocrinology, as recipient of the 2026 Edwin B. Astwood Award for Outstanding Research in Basic Science. He is a professor of cellular and molecular medicine and professor of medicine at the University of California San Diego in San Diego. We asked about his path to macrophage research as well as the advice he shares with the young postdocs on his team.

Endocrine News: The award is named after Dr. Edwin Astwood who is known for his contributions to the treatment of hypothyroidism. What did hearing the news of the award mean to you?

Glass: This award has gone to many of the all-stars of basic science and endocrinology over the years, so being included in that group was really thrilling. Getting the phone call that I had been awarded this honor just put a spring in my step. Especially now when there’s so much bad news, having some incredibly good news come along was really rejuvenating.

EN: Do you recall when you first realized that science would be your career?

Glass: It was a bit of a process, really. I was an undergrad biophysics major at UC Berkeley with a long-term interest in being a physician. I went from being an undergraduate at Cal to UC San Diego to start medical school with the idea of being a physician, but I was also attracted to UC San Diego as a very young medical school that put the science of medicine as one of its core principles. And so, it was really that transition into the UCSD environment and getting connected with some mentors very early on who were great physician-scientists who pointed me in the direction of doing biomedical research.

“The research on the steroid hormone receptors indicated that they were actually inside the cell, and they were transcription factors that were regulated by the hormones. And I was just sort of knocked over by that. It was the very beginning of a new field of molecular endocrinology…” — Christopher Glass, MD, PhD, professor of cellular and molecular medicine, professor of medicine, University of California San Diego, San Diego, Calif.

And to make a long story, short, even though I went to UC San Diego as a straight medical student, my experiences there with the faculty led me to enroll in the MD-PhD program and what I worked on as a graduate student was lipoprotein metabolism. And then I finished my clinical training and was launched as a physician-scientist.

EN: How did exploring macrophages become your life’s work?

Glass: So that also was not a completely linear path. As I mentioned, I worked on lipoproteins when I was a graduate student, and at that time, some of the major discoveries that had to do with cholesterol metabolism were being made by the labs of Brown and Goldstein at University of Texas Southwestern. They had worked out what we call the LDL receptor pathway and that’s the pathway that is targeted by statins, which are the most common form of medicines used to lower cholesterol levels. We knew from their studies and others that macrophages were very important in cardiovascular disease, and that it’s the macrophage within the arterial wall that is the cell that accumulates cholesterol and begins the process of atherosclerosis that then leads to cardiovascular disease. There were people in the lab where I was working on that, so that relationship was embedded in my mind.

When I later left UCSD to do my internship and residency, I went to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital with the idea that I would be a cardiologist, and that I would study lipids and cardiovascular disease. It was while I was in Boston that some major discoveries related to regulation of gene expression were made. And some of the first discoveries that related to the steroid hormone receptors were made that indicated that steroid receptors were not like other classes of receptors that were well known at the time, like insulin receptors, which are on the cell surface. The research on the steroid hormone receptors indicated that they were actually inside the cell, and they were transcription factors that were regulated by the hormones. And I was just sort of knocked over by that. It was the very beginning of a new field of molecular endocrinology, so in mid-stride at Boston, I changed my career focus from being a cardiologist to be to becoming an endocrinologist…And with that new perspective of my career path, I looked for researchers who I could do a post-doc with and learn about how hormones regulate gene expression through this class of proteins. I ended up back here at UCSD working with Geoff Rosenfeld. He was then and still is one of the leading investigators in studying hormone-dependent gene expression.

So now, I thought how can I put those two things together in a new way that would allow me to make a significant impact on research going forward? And that’s when I remembered macrophages. No one knew how they were regulated at the level of gene expression, so when I started my laboratory, it was really to understand the molecular mechanisms that controlled macrophage development and function. And the initial emphasis was on studying roles of macrophages in cardiovascular disease, and to study the genes that enabled macrophages to take up cholesterol particles in the arterial wall that would lead to cardiovascular disease. So, that’s it in a nutshell.

EN: How has the Endocrine Society played a role in your career?

Glass: I’ve been a long-standing member of The Endocrine Society since I’ve been a postdoc, so that’s a long time. I’ve had a consistent thread of activity with The Endocrine Society. Most recently, I was a member of the Laureate Awards Committee, and I actually chaired that committee for a year. That’s probably my most significant service to the Society. But you know, between The Endocrine Society and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, those have been pillars of my professional career.

EN: Your Glass Laboratory boasts a great diverse team including postdocs, undergraduates, and a mathematician. Is there a core methodology or life lessons that you offer your team?

Glass: What I tell postdocs who are thinking about heading off on their own, and setting up their new laboratory, is they have to find the intersection between three different facets of biomedical science.

The first facet is they need to latch on to some problem that they’re absolutely passionate about and they must solve it. So, given that there are lots of those types of problems that you could become passionate about solving, then the next thing that you have to do is figure out which of those problems intersect a significant unmet medical need. And so, if you can do that, then all of a sudden the significance of whatever that problem is that you’re working on goes way up. That’s the second piece of advice. And then the third factor is that it has to be fundable. You cannot do science without money, and it costs more than ever to push our boundaries of knowledge to the next level. So, that’s the third essential pillar of the three pillars.

To the extent that I can help my post-docs shape their vision and let them leave the lab and hit the ground running, that’s one of my goals, as well.

“You cannot do science without money, and it costs more than ever to push our boundaries of knowledge to the next level.” — Christopher Glass, MD, PhD, professor of cellular and molecular medicine, professor of medicine, University of California San Diego, San Diego, Calif.

EN: When you’re not in the lab what’s your favorite pastime to unwind?

Glass: One of the things that I do, almost every day, before I come in to work, is I swim. I was a competitive swimmer in college and high school, and I’ve just continued to love swimming as a form of exercise. But what’s great about San Diego is that not only can I swim in the pool, which I do frequently in the winter, but in the spring, summer, and fall, the ocean warms up, and I can swim in the ocean. This is one of the few places in the world where you can go for a swim in the ocean and be in your office by 8:30. So for me, that’s been the way I stay fit and active, and it clears my brain, so that when I get into the office, I’m absolutely awake and ready to go.

The Endocrine Society will present Glass with the Outstanding Research in Basic Science Award at ENDO 2026 being held June 13-16, in Chicago, Ill.

—Shaw is a freelance writer based in Carmel, Ind., and a regular contributor to Endocrine News. She writes the monthly Laboratory Notes column.