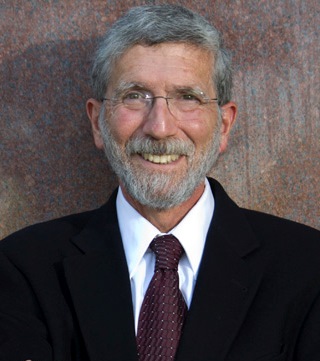

Endocrine News talks with Dennis M. Styne, MD, chair of the task force that created the latest Clinical Practice Guideline on pediatric obesity. He tells us about the latest recommendations in treating these patients and how not all treatments are dependent on the physician.

The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, “Pediatric Obesity — Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline,” was released last month and advises healthcare providers on how to prevent this burgeoning epidemic with a variety of lifestyle changes.

Intensive, family-centered lifestyle modifications to encourage a healthy diet and activity remain the central approach to preventing and treating obesity in children and teenagers, says the guideline’s task force chair, Dennis M. Styne, MD, of the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento. “Since the Society last issued a pediatric obesity guideline in 2008, physicians have access to new information on genetic causes of obesity, psychological complications associated with obesity, surgical techniques and medications that are now available for the most severely affected older teenagers. The guideline offers information on incorporating these developments into patient care.”

Endocrine News sat down with Styne to find out why this guideline is such a valuable tool for endocrinologists who treat pediatric patients.

Endocrine News: For endocrinologists familiar with the 2008 Pediatric Obesity guideline, what changes can they expect to see in the new guideline?

Dennis Styne: The reader will notice extensive updates in all areas. The presentation of the epidemiology of childhood obesity is updated with reference to the apparent stabilization at about 17% of the U.S. child and adolescent population, although a rise in the prevalence of extreme obesity is apparent. While we still favor the use of the BMI in the evaluation of childhood obesity we comment on its limitations in view of different degree of total fat and distribution between racial/ethnic groups. It is important to augment BMI percentile information with clinical judgement to identify the child who is overweight.

The approach to childhood obesity is daunting and can awaken defensiveness in parents. If the provider cannot provide supportive, empathetic care to the child and family, it is best to defer to a provider who can.

In the evaluation of childhood obesity, it is important to recognize the new lower upper limits of the normal range of values for alanine transaminase (ALT) in the investigation of alcoholic fatty liver disease (25 for boys and 22 for girls). We highlight the lack of utility of the measurement of plasma insulin in evaluation as well as turning the clinician away from the evaluation for an underlying endocrine disorder in the absence of attenuated growth rate in most cases. The completely reworked section on the genetics of obesity emphasizes that approximately 7% of obese children have a genetic basis and we indicate that a genetic valuation is indicted in those children who exhibit hyperphagia, develop obesity before five years of age, and have parents with severe obesity. We could not find strong evidence to support breast feeding a method of prevention of the development of obesity. With only one medication approved for obesity in children we caution the use of the medications approved for adults in subjects under 16 years of age and only with an experienced investigator. We review the growing evidence on the effects of bariatric surgery and support the existing guidelines for use on the appropriate mature, older adolescent subjects who may benefit.

- Children or teens with a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile should be evaluated for related conditions such as metabolic syndrome and diabetes.

- Youth being evaluated for obesity do not need to have their fasting insulin values measured because it has no diagnostic value.

- Children or teens affected by obesity do not need routine laboratory evaluations for endocrine disorders that can cause obesity unless their height or growth rate is less than expected based on age and pubertal stage.

- About 7% of children with extreme obesity may have rare chromosomal abnormalities or genetic mutations. The guideline suggests specific genetic testing when there is early onset obesity (before five years old), an increased drive to consume food known as extreme hyperphagia, other clinical findings of genetic obesity syndromes, or a family history of extreme obesity.

EN: What was the main reason for the revision of the guideline?

The epidemic of pediatric obesity remains an ongoing serious international health concern which deserves constant evaluation and attention. With over 1,778 new references listed on Pubmed addressing childhood obesity since the publication of the initial guidelines we strove to incorporate recent advances in the field. Many pediatric obesity studies have further clarified the difficulties associated with prevention and treatment with lifestyle changes and the need for primary prevention of childhood obesity through local, national, and international cooperative efforts.

Due to the difficulty in treating pediatric obesity and the frequent lack of long-term success, we emphasize once again that addressing lifestyle is key in preventing and treating childhood obesity.

EN: What are the key take home messages for patients in this guideline?

Due to the difficulty in treating pediatric obesity and the frequent lack of long-term success, we emphasize once again that addressing lifestyle is key in preventing and treating childhood obesity. The approach to childhood obesity is daunting and can awaken defensiveness in parents. If the provider cannot provide supportive, empathetic care to the child and family, it is best to defer to a provider who can.

EN: What are your hopes for the impact of this guideline on the standards of care of the pediatric obese patient?

We hope that providers will use the information in this evidence-based document to evaluate all children they see for the possibility of childhood obesity and to thoroughly investigate affected children and teenagers for comorbidities. We hope that they will utilize the information presented on prevention and treatment of childhood obesity to address their young patients and their families in a sensitive and nonthreatening manner. For the more severely affected older adolescents we provide guidelines for the situations in which bariatric surgery might be appropriate, but only if an experienced team is available. However, we caution providers lacking experience in the use of medications targeting obesity from using these agents in children, especially those under the age of 16 years. We also provide guidelines for a provider to determine who would be an appropriate candidate for bariatric surgery.

EN: How do you expect other medical specialties to be affected by your recommendations?

With childhood obesity being epidemic, providers who see children will unequivocally encounter obese children. While it might not be the focus of their field, these providers must be aware of the methods of diagnosis and evaluation of comorbidities that are present. Even if they are not in a clinical situation in which they can participate in the treatment of childhood obesity they certainly can refer the child to an endocrinologist or other appropriate providers to assist in the care of their young patients.

The guideline was published online at www.endocrine.org/KidsObesity, ahead of print.