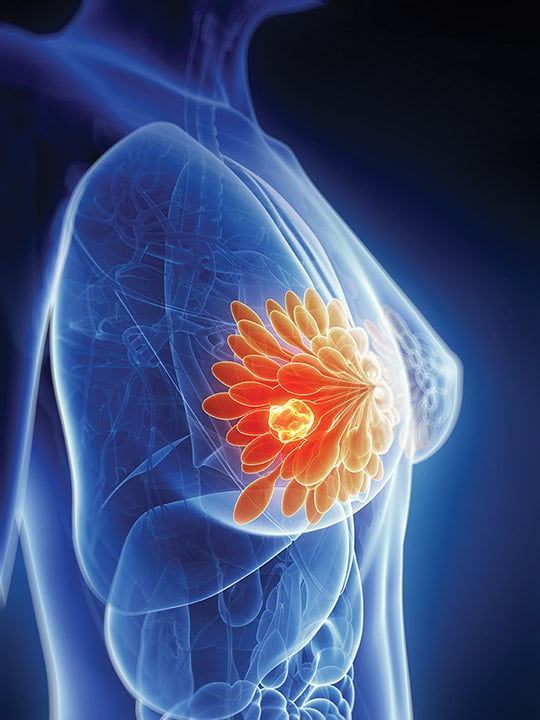

A new study presented at ENDO 2016 revealed a possible link between bisphenol A exposure in utero to breast cancer later in life. In the process, the researchers created a new bioassay that can test chemicals much faster than typical animal studies.

Almost every single person alive today has detectable amounts of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in his or her body, according to the 2015 joint Endocrine Society/IPEN publication Introduction to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): A Guide for Public Interest Organizations and Policy-Makers.

These EDCs — phthalates (plasticizers), bisphenol A (BPA), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and others, in their bodies — are hormone-like industrial chemicals that did not even exist 100 or so years ago. Studies on human populations consistently demonstrate associations between the presence of certain chemicals and higher risks of endocrine disorders such as impaired fertility, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer.

Ubiquitous BPA

The xenoestrogen BPA is especially prevalent as a component used in rigid plastic products such as compact discs, food and beverage containers, food and formula can linings, and glossy paper receipts. In the case of food containers, when they are heated or scratched, the BPA can seep out into the food and then be ingested. BPA also escapes from water pipes, dental materials, cosmetics, and household products among others and is released into the environment or directly consumed. According to research, such exposures help account for why BPA has been found in the urine of a representative sample of 95% of the U.S. population.

“…BPA acts directly on the mammary gland and that this effect is dose dependent: A low dose significantly increased ductal growth, whereas a high dose decreased it.” – Lucia Speroni, PhD, research associate, Soto-Sonnenschein Lab, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston

As the now-familiar “developmental origin of health and disease” hypothesis, which posits that a poor start to life during gestation can lead to disease in adulthood, would suggest, even low doses of chemicals that interfere with hormone actions are particularly detrimental when exposures happen during development. Researchers have long suspected that EDC exposures can be especially problematic for females, impairing reproductive functions throughout their lives as well as being associated with increasing rates of the reproductive cancers — breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers.

Notably, BPA can cross the placenta in the womb, indirectly exposing the fetus — it has been found in both maternal and fetal serum as well as neonatal placental tissue. Newborns can also be directly exposed through breastfeeding.

Direct Effects

The results of a study presented at ENDO 2016 provide compelling support for the idea that fetal exposure to BPA might increase risk for development of breast cancer in adulthood; in fact, it may explain why overall incidence increased in the 20th century. Lucia Speroni, PhD, a research associate and member of the Soto-Sonnenschein lab at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston and the study’s lead investigator, reports, “We found that BPA acts directly on the mammary gland and that this effect is dose dependent: A low dose significantly increased ductal growth, whereas a high dose decreased it.”

Because BPA is a ligand for several hormone receptors and acts on multiple organs, the researchers sought to develop an in vitro bioassay that could determine whether BPA acts directly on the fetal mammary gland. “This represents a novel approach to study the effects of hormones and hormonally active chemicals on the developing fetal mammary tissue outside the organism,” Speroni says. For the bioassay, mouse mammary buds were extracted at Day 14 of development and grown in culture for five days, after which, the explants were exposed to BPA. Changes in the growth of the mammary gland were then recorded and compared to controls, rapid results that were available in less than a week.

“Because these effects are similar to those found when exposing the fetus through its mother, our experiment suggests that BPA acts directly on the fetal mammary gland, causing changes to the tissue that have been associated with a higher predisposition to breast cancer later in life,” Speroni explains. In replicating the process of mammary gland development in vitro, this method additionally allows for live observation throughout the whole process. “By having the organ growing in a dish,” Speroni says, “we are now able to observe how the mammary gland develops in real time, something that was impossible to do using live animals. The culture model will help us answer questions that could not be addressed until now for lack of appropriate culture systems, such as elucidating the mechanism of action of BPA on the mammary gland.”

A Budding Bioassay

The lab team had previously shown that the most harmful time for exposure to BPA is during fetal development by causing alterations in the developing mammary gland. “Thus, there is a clear need to improve the process of identification of chemicals that, by affecting organ development, may increase the risk of developing cancer in adulthood,” Speroni says.

Current methods can detect hormonal activity (i.e., whether a certain compound could be mistaken by our bodies for a hormone) only in regards to cell proliferation or death, lacking a tissue-dependent context — they cannot show that a chemical has changed the development of an organ.

“…there is a clear need to improve the process of identification of chemicals that, by affecting organ development, may increase the risk of developing cancer in adulthood.” – Lucia Speroni, PhD, research associate, Soto-Sonnenschein Lab, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston

“In an ideal world, the precautionary principle would be used, and chemicals with estrogenic activity would be considered potential breast carcinogens, based on the results obtained in rats and mice exposed to diethylstilbestrol and BPA,” Speroni says. “However, regulatory action requires extensive long and costly animal studies. In vitro assays could expedite the process and allow researchers, regulatory agencies, and industries to test various hormone-mimicking compounds when determining their likelihood to contribute to breast cancer.”

Because results are available in such a short period of time, the bioassay could also be used to screen a large number of chemicals of interest for their mammary gland toxicity.

In the meantime, women may choose to limit their exposure to chemicals that act like estrogen and thereby increase their risk of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

-Horvath is a freelance writer based in Baltimore, Md., She wrote about the likelihood of sedentary kids developing diabetes in adulthood in the July issue.