As obesity rates continue to climb so does metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), often at an alarming rate. Endocrine News talks to Theodore C. Friedman, MD, PhD, and Magda Shaheen, MD, PhD, about research they presented at ENDO 2023 on fatty liver disease’s link to diabetes, what impact new medications could have, and how endocrinologists can help stem the tide.

As of now, about 42% of Americans have obesity – a condition that needs no introduction here, but certainly needs to be revisited from time to time. In seven years or so, half of Americans are projected to have obesity, which of course carries with it all kinds of comorbidities, including fatty liver disease — which has no cure, but can be successfully treated by treating the underlying condition of obesity. But things have gotten tricky.

The percent of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is increasing in U.S. adults, according to a study presented at ENDO 2023. And the rate of fatty liver disease is outpacing that of obesity.

MAFLD, alternatively known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is fast becoming the most common indication for liver transplantation. It is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. If untreated, MAFLD can lead to liver cancer and liver failure.

Magda Shaheen, MD, PhD, MPH, MS, program director, Master of Science in Clinical Research Program, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

“MAFLD affects Hispanics at a higher prevalence relative to Blacks and whites. This racial/ethnic disparity is a public health concern,” says researcher Theodore C. Friedman, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Internal Medicine at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science and the lead physician in endocrinology at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Outpatient Center in Los Angeles. “Overall, the increase in MAFLD is concerning, as this condition can lead to liver failure and cardiovascular diseases and has an important health disparity.”

The researchers analyzed data for 32,726 participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1988 to 2018. “We found that overall, both MAFLD and obesity increased with time, with the increase in MAFLD greater than the increase in obesity,” Friedman says.

“MAFLD is defined as fatty liver disease (FLD) with overweight/obesity, evidence of metabolic dysregulation, or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as FLD without excessive alcohol consumption or other causes of chronic liver disease.”

Magda Shaheen, MD, PhD, MPH, MS, program director, Master of Science in Clinical Research Program, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

“The percent of people with MAFLD increased from 16% in 1988 to 37% in 2018 (a 131% increase) while the percent of obesity rose from 23% in 1988 to 40% in 2018 (a 74% increase),” the study’s first author Magda Shaheen, MD, PhD, MPH, MS, program director, Master of Science in Clinical Research Program, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, said in a statement. “The prevalence of MAFLD increased faster than the prevalence of obesity, suggesting that the increase in the other risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension may also contribute to the increase in the prevalence of MAFLD.”

Among Mexican Americans, the percent of MAFLD was higher at all times compared to the overall population. The percent increase of MAFLD in 2018 relative to 1988 was 133% among whites, 61% among Mexican Americans and 56% among Blacks.

These findings coincide with those reached by Friedman and his co-authors of a paper recently published in Frontiers of Endocrinology, in which the authors conclude, “that prediabetes and diabetes populations had a high prevalence and higher odds of NAFLD relative to the normoglycemic population and HbA1c is an independent predictor of NAFLD severity in prediabetes and diabetes populations.”

Endocrine News caught up with Friedman and Shaheen to talk about this alarming increase in fatty liver disease, diabetes’s relationship with fatty liver disease, and what can be done to curb this trend.

Your ENDO study shed light on some pretty troublesome findings. What are the implications for this increase in the prevalence of fatty liver disease?

Theodore C. Friedman: Some patients with fatty liver will go on to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis and require a liver transplant. It’s also associated with increased cardiovascular disease. It’s a common disease getting more common. As we pointed out, it’s growing more than just obesity is. I think it’s a bad diet, unhealthy things, more diabetes, more fatty liver disease, more obesity. I think endocrinologists need to be at the forefront of pushing healthy lifestyle and getting our patients, no matter what they say, to try to be better, exercise more, and be healthier.

Can you talk a little bit about the difference between NAFLD to MAFLD?

Magda Shaheen: MAFLD is defined as fatty liver disease (FLD) with overweight/obesity, evidence of metabolic dysregulation, or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as FLD without excessive alcohol consumption or other causes of chronic liver disease.

TCF: We and other endocrinologists prefer the term MAFLD because 1) that reflects that it’s an endocrine disease and needs to be on endocrinologists’ radar; 2) it reflects the metabolic nature of the condition; and 3) it’s not defined by the absence of alcohol. Some people with fatty liver disease may consume alcohol.

We spoke before about the disparities of fatty liver disease affecting Hispanics more than Black or white people, and that it affects Mexican Americans even more so among Hispanics.

TCF: Correct, the rate of [liver disease in] Hispanics that are not Mexican Americans is similar to other races. Mexican Americans should especially be screened for MAFLD and have ethnically appropriate interventions.

The fact that liver disease seems to be outpacing obesity is, again, troubling. What does this mean for patients and the physicians treating them? And in your opinion, what can be done to curb this trend?

TCF: More awareness and testing and emphasis on better diet and more exercise. I deal with mostly low income, mostly Hispanic patients, and I’ve been at Martin Luther King since 2000. In the beginning, there was very little awareness of diet and exercise. I had some patients who weighed 300 pounds; they came in with cellulitis and infections. And they said, “Nobody ever talked to me about losing weight.” Now, everybody knows about adopting a healthy lifestyle. People, regardless of where they live and their education, they’ve heard it before. They may not know some specifics. They may not know some hints. They may not know exactly what to eat. I think there’s a lot of missing information about what kind of food to eat.

“[Metabolic associated fatty liver disease] is a serious and increasing condition related to metabolic dysfunction, prediabetes, and diabetes, and is increasing with time. A better lifestyle is needed to stem the tide.”

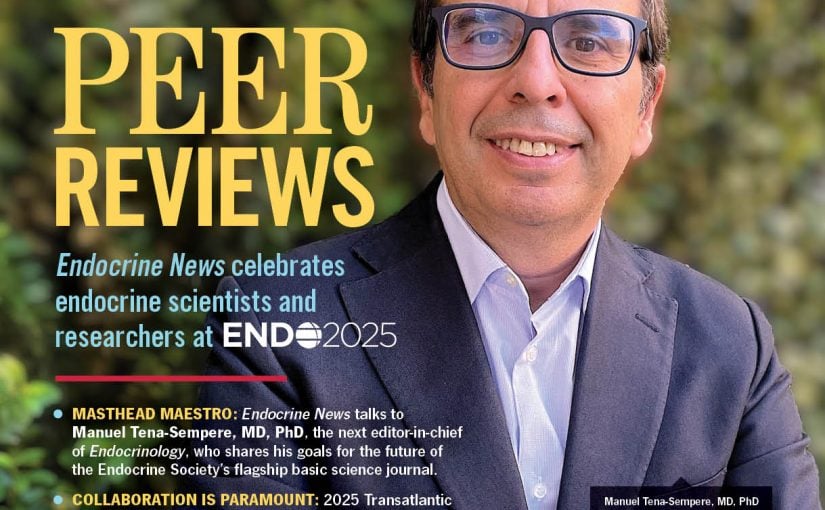

Theodore C. Friedman, MD, PhD, chair, Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

I think the art of this is how to motivate people, how to figure out what their barriers are, and how to inspire them to change. We do an obesity group visit at MLK, and we talk about these things. We’re actually starting a lifestyle medicine group visit with our family medicine and internal medicine residents, which is a big effort. I think a group setting is probably better than an individual setting; you get more inspiration from the audience and people buy into it. We talk a little bit about fatty liver disease and why it’s important to prevent it. I think this is what endocrinologists need to be doing these days, in addition to giving people insulin, for example, they need to spend a good portion of their visit really trying to get them motivated to improve their lifestyle.

Is there any interest in Ozempic or these new weight loss, anti-obesity medications?

TCF: Ozempic does help with fatty liver disease. Mounjaro does also. For patients who are appropriate to go on them, I use them, mostly for people already with diabetes who are at the stage of their diabetes that they would either go onto insulin or to go onto one of these medicines. I would have them go on Ozempic/Mounjaro.

I think it brings up two points. One is, people often eat unhealthy foods, and if they can have decreased cravings for these unhealthy foods — which Ozempic does — it takes away some of your cravings for junk foods. You’re not as hungry, so when you drive by that Jack in the Box, you’re not going to pull over just because you’re not that hungry. It gets people to stop eating as much and have more money, just because they’re not spending it all on food. They have more time. They feel better for the most part, and they see good results.

On the other hand, I think the mainstay treatment for obesity, diabetes, and MAFLD should be lifestyle changes and diet and exercise that people should be doing without having to take a medicine that often costs $1,000 a month, lead to some fair amount of side effects, and potentially bankrupt healthcare systems.

Now to the Frontiers paper. It seemed to dovetail with the presentation at ENDO and answer some questions as to why fatty liver disease is outpacing obesity.

TCF: Definitely. They’re both related.

Can you speak more to the “bidirectional relationship” of diabetes and liver disease?

TCF: Diabetes clearly leads to more liver disease — the higher the A1c, the more fatty liver disease. We did correlations, so we can’t say for sure if more severe liver disease leads to more diabetes. I think it’s clear diabetes and pre-diabetes lead to fatty liver disease, but there is a paper that supports fatty liver disease leads to diabetes.

“Diabetes clearly leads to more liver disease — the higher the A1c, the more fatty liver disease. We did correlations, so we can’t say for sure if more severe liver disease leads to more diabetes. I think it’s clear diabetes and pre-diabetes lead to fatty liver disease, but there is a paper that supports fatty liver disease leads to diabetes.”

Theodore C. Friedman, MD, PhD, chair, Department of Internal Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

[Shaheen points to a 2021 paper by Khneizer et al, who write, “There is a close bi-directional relationship between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); NAFLD increases the risk for T2DM and its complications whereas T2DM increases the severity of NAFLD and its complications.”

You write about the need for glycemic control to reduce the odds of severe NAFLD.

MS: Our study showed that among those with prediabetes and diabetes, increased A1C was associated with an increased chance of NAFLD.

TCF: Studies have shown that any anti-hyperglycemic agent improves NAFLD, including both those know to improve liver disease like pioglitazone and GLP-1 receptor agonists, but also other diabetes drugs like sulfonylureas.

MS: Three antidiabetic drugs (TZD, DPP-4Is and GLP-1RAs) are effective in reduction of liver enzymes. SGLT2Is and GLP-1RAs were superior to other diabetes medications in reducing liver fat fraction. Recent studies have reported that metformin can improve insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia and may aid in the treatment of NAFLD. Evidence from animal and human studies has indicated that metformin may reduce the onset and progression of NAFLD.

You write, “The current study confirms that NAFLD needs to be included in the list of conditions that subjects with prediabetes may develop.” Is there still a gap in that area?

TCF: Yes, many people think prediabetes is a benign condition that isn’t associated with other diseases.

NAFLD itself has a racial disparity.

MS: Yes, racial/ethnic disparity existed where Mexican Americans have a higher prevalence of NAFLD and Blacks have lower prevalence of NAFLD.

Were you surprised to find no racial/ethnic disparity among those with prediabetes and diabetes?

TCF: A bit, but since Mexican Americans have both more liver disease and prediabetes/diabetes, when adjusted for race/ethnicity there was no effect.

MS: When we adjust for demographics, there was a racial/ethnic disparity in those with prediabetes. However, after adjusting for behavioral variables, the difference between Mexican Americans and whites was not observed, suggesting that one or more of the behavioral variables can account for the racial/ethnic difference.

What’s the main thing you hope readers will take away from both of these studies and this article?

MS: For those with prediabetes and diabetes, glycemic control is important to reduce the chance of NAFLD and prevent the progression of the disease.

“Recent studies have reported that metformin can improve insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia and may aid in the treatment of NAFLD. Evidence from animal and human studies has indicated that metformin may reduce the onset and progression of NAFLD.”

Magda Shaheen, MD, PhD, MPH, MS, program director, Master of Science in Clinical Research Program, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine & Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

TCF: MAFLD is a serious and increasing condition related to metabolic dysfunction, prediabetes, and diabetes, and is increasing with time. A better lifestyle is needed to stem the tide.

Bagley is the senior editor of Endocrine News. In the August issue, he wrote about some of the breaking scientific news that was presented at ENDO 2023.