Hepatic steatosis — more commonly known as fatty liver disease — appears to have a disproportional effect on Hispanic Americans, with Mexican Americans at an even higher risk. A better understanding of these risk factors is crucial to creating better individualized care protocols for these patients.

In 2018, the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities announced a funding opportunity to study health disparities as they relate to liver disease. In 2009, researchers at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, and University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville, Fla., were funded to examine who is at a higher risk of developing hepatic steatosis, as well as the mechanisms that drive this disease.

Previous studies and literature had shown hepatic steatosis is a growing problem worldwide, and health disparities around the disease are coming into sharper focus. Hispanics carry a higher risk of getting fatty liver disease, while African Americans have a lower risk, but it’s been unclear why – a common thread when it comes to understanding this relatively new disease. While medical journals cover fatty liver as much as anything else, the disease that may soon be the main reason for a liver transplant doesn’t always show up on providers’ radars.

- Hepatic steatosis is a growing problem worldwide, and many health disparities surround this disease.

- Until recently, researchers thought that Hispanic Americans overall had a higher rate of hepatic steatosis, but a new study shows Mexican Americans have a much higher risk for developing disease than other Hispanics.

- The finding not only speaks to personalized medicine but may shed some light onto what causes hepatic steatosis.

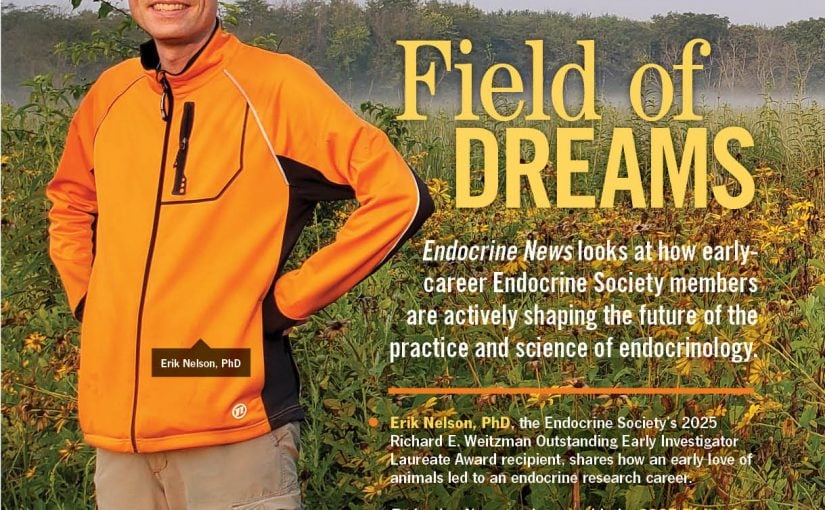

“In general, it’s this huge disease that we don’t really understand, that we have limited treatments for,” says Theodore Friedman, MD, PhD, chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Molecular Medicine at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles, Calif., who is leading the Charles R. Drew University investigators. “We have this grant on a fairly small part of fatty liver disease on why Hispanics have a higher rate, but I think it will answer some of the other questions, like what causes the disease.”

“You have to look at people. They’re not all the same. They have different risk factors. You think Hispanics would be similar but they’re not. And understanding some of the mechanisms of why, how much of this is genetic versus what they eat, or other lifestyle factors. I think that’s a crucial issue and it’s one we’re trying to get at.

Theodore Friedman, MD, PhD,

And they may be on to something. This past summer, Friedman and his team published a paper entitled “Reassessment of the Hispanic Disparity: Hepatic Steatosis is More Prevalent in Mexican Americans than Other Hispanics” in Hepatology Communications that challenges the previous paradigm that hepatic steatosis is higher in Hispanics overall. The researchers found that hepatic steatosis is higher in Mexican Americans, but not in non-Mexican American Hispanics, a conclusion the researchers hope not only helps bring awareness to clinician endocrinologists who see Hispanic patients, but also might lead to understanding the exact factors that cause fatty liver disease.

Answers Leading to More Questions

For this study, Friedman and his team used the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017-2018 to analyze data of 5,492 individuals 12 years and older diagnosed with hepatic steatosis with FibroScan using controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) values. Friedman points out this updated NHANES database broke down Hispanics in Mexican Americans and other Hispanics, which made his group able to look at the question of Mexican Americans versus other Hispanics. Until recently, the databases had lumped all Hispanics together.

“One of the things we were concerned about is: Hispanics are different types; is it really all Hispanics versus one type or another?” Friedman says. “Most of the articles have been vague about that. Most of the articles coming from Southwest United States, a lot of work with them in San Antonio, Texas. Most of [the participants] were Mexican Americans. If you looked at work done in Florida, for example, it might be much more Central Americans or Cubans and Puerto Ricans. We were interested in that.”

The researchers found that the prevalence of severe steatosis was highest among Mexican Americans (42.8%), 27.6% in other Hispanics, 30.6 % in non-Hispanic whites, and lowest among non-Hispanic African Americans (21.6%). Mexican Americans were about two times more likely than whites to have moderate-to-severe hepatic steatosis, while other Hispanics showed no difference from whites.

“This is an important finding as it shows that Hispanics are not a monolith and that conditions like hepatic steatosis are more common in specific subgroups of Hispanics, such as Mexican Americans and not in other Hispanics,” Friedman says.

An important finding indeed, and one that speaks further to personalized, tailored care. This finding means a clinician who sees Mexican Americans, as well as Central Americans or Cuban Americans, should carefully consider that the Mexican American patient has a higher risk for fatty liver disease. “I think we need a culturally and linguistically adapted interventions that involve community and providers to increase awareness and screening for hepatic steatosis especially among Mexican Americans for early detection and prevention of organ damage,” says Magda Shaheen, PhD, MPH, MS, FACE, the first author of the paper, associate professor at Charles Drew University, and director of the AXIS Research Methods and Biostatistics Unit.

Friedman breaks it down even further: “We’re finding it much more common in male than female Mexican Americans. So, if you have a Mexican American male, your doctor should especially search out fatty liver disease.”

He recommends ordering ultrasounds or FibroScan for these patients, with a low threshold. These patients should be encouraged to lose weight and exercise more (the first line of treatment of fatty liver disease). Friedman also notes there are several medications available that work, but not as well as clinicians and patients might like. “Pioglitazone I think is probably the best medicine for treating this right now,” he says.

But with any important finding, the answers often lead to more questions, ones that Friedman and his team are eager to investigate.

Paving New Avenues of Exploration

In the Discussion section of the Hepatic Communications paper, Shaheen, et al. write that few studies have identified risk factors for hepatic steatosis in general, since most researchers tend to focus on specific forms of liver disease. For Friedman and this team, the finding that Mexican Americans have a higher prevalence of fatty liver disease compared to people from other backgrounds like Cuban, Dominican, or Puerto Rican, has begun to pave some new avenues to explore.

The researchers point to possible genetic factors: the PNPLA3 G allele, which is associated with greater severity of NAFLD, might be varied in Mexican Americans, a variation that could contribute to this disparity. However, that investigation could take some time.

“It’s a long, involved process with the CDC to get access to genetic information available in NHANES,” Friedman says. “They have to test a lot of the security issues. And then with COVID-19, this was put on hold. We are going to, in the next year, start looking at a bunch of genes that seem to be correlated. But we’re going to specifically look, are these genes involved in the cause of why the Mexican Americans have this higher rate of hepatic steatosis?”

Then there are possible non-genetic factors. Soda consumption may be a risk factor, high-carb diets another. But Friedman points to pre-diabetes and diabetes as clear risk factors, and ones that should sound the alarm for possible fatty liver disease, especially for a Mexican American patient. “People think that pre-diabetes is just ‘pre,’ that it doesn’t have any detrimental effects. And it really seems like the people with pre-diabetes are at much higher risk for this and you should intervene on them also.”

“People think that pre-diabetes is just ‘pre,’ that it doesn’t have any detrimental effects. And it really seems like the people with pre-diabetes are at much higher risk for this and you should intervene on them also.” – Theodore Friedman, MD, PhD, chief, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Molecular Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, Calif.

Researchers at University of Florida College of Medicine are using parts of the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant to take liver samples from people undergoing gastric bypass and looking at the genes in the liver, even breaking it down to different genes in Hispanics versus Caucasians who undergo get a liver biopsy. The group at Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine is looking at cell cultures.

Friedman’s team’s work with the NHANES database may have uncovered some of the pathways to fatty liver disease. The disease is twice as common now than it was 30 years ago, and since it’s a metabolic disease, it will be up to endocrinologists to help curb that trend. (There is the question of whether the medical community just has better ways to detect fatty liver disease now; Friedman tells Endocrine News he thinks it really is twice as common.)

For now, at least, this finding speaks again to caring for each patient as an individual. Mexican American patients in Texas live different lives than Cuban American patients in Florida. “You have to look at people,” Friedman says. “They’re not all the same. They have different risk factors. You think Hispanics would be similar but they’re not. And understanding some of the mechanisms of why, how much of this is genetic versus what they eat, or other lifestyle factors. I think that’s a crucial issue and it’s one we’re trying to get at.”

Bagley is the senior editor of Endocrine News. He wrote the September cover story on Stanley Andrisse, PhD, MBA, and his remarkable transformation from troubled youth to renowned researcher.