As obesity and diabetes rates continue to climb, so too do rates of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). A CEU 2021 session will teach attendees how to identify NAFLD as well as the best treatment protocols.

As it stands, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is on track to overtake viral hepatitis as the leading cause of liver transplantation in the U.S. The most common cause of chronic liver disease, NAFLD includes simple steatosis (NAFL) and a more severe and progressive form of liver disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis under its umbrella.

What makes the fact that NAFLD is becoming more widespread so important is that the two drivers of the disease – obesity and type 2 diabetes – continue to increase. Currently, 42% of Americans are obese while another third is overweight, and it’s no secret that diabetes rates continue to climb, particularly among minority communities. In just nine years, half of Americans are projected to be obese.

According to Kenneth Cusi, MD, chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at the University of Florida in Gainesville, until now, endocrinologists have been unaware of the significance of fatty liver in their patients, and by not acting early on, physicians have been unable to prevent cirrhosis in many of these patients. “As endocrinologists, we see these people every day in the clinic,” he says. “So if you’ve not diagnosed somebody with steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in the past week, you might’ve missed several patients in a whom you could have started to prevent cirrhosis.”

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) rates rising as its two drivers – obesity and type 2 diabetes – continue to increase.

- However, until now, endocrinologists have been unaware of the significance of fatty liver in their patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes, and that knowledge gap has left physicians unable to prevent cirrhosis in many patients.

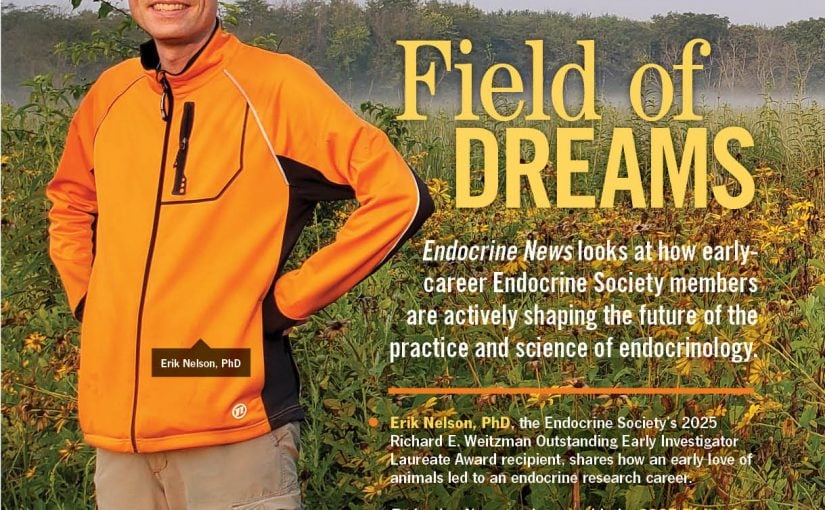

- For his upcoming CEU session, Kenneth Cusi, MD, will discuss how to identify fatty liver in patients early on, as well as how to best treat this complex disease.

Cusi will bring his experience, as well as a call to action, to this year’s virtual Clinical Endocrinology Update, once again beamed to computer screens and devices around the world, in his talk titled “What Endocrinologists Need to Know about Diagnosis and Management of Fatty Liver” on September 10 at 1:15 p.m. (EST). He hopes to address these knowledge gaps among endocrinologists and other physicians, as well as correct some misconceptions still held among the medical community.

Younger Patients at Risk

Cusi says that physicians have historically been trained to only be concerned about liver disease when a patient’s alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are above 40 IU/ml. But the normal plasma ALT for a woman is 19 IU/ml and 30 IU/ml for a man. “Any time you see somebody with a value above 30 IU/ml, those people typically will already have fatty liver,” he says.

In fact, 70% of people with type 2 diabetes have a fatty liver, and of these about 20% have fibrosis, which can lead to cirrhosis if left untreated. A paper published this past February in Diabetes Care by Lomonaco, et. al. (Cusi was a co-author) concludes that based on those kind of numbers physicians should “screen for clinically significant fibrosis in patients with [type 2 diabetes] with steatosis or elevated ALT.”

“We know that all patients that have [fatty liver] have insulin resistance, whether they’re lean or obese, and this insulin resistance combines with some other factors in the liver that are probably genetically determined to trigger inflammation and activate pathways that promote liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Our mission as endocrinologists is to identify patients early on.” – Kenneth Cusi, MD, chief, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla.

Those numbers should also mean endocrinologists are seeing more cases of cirrhosis in the clinic. But the epidemic of obesity has only really spread in the last 20 years or so, and Cusi says it takes about 20 or 30 years to develop cirrhosis. Another reason endocrinologists do not encounter much cirrhosis is because once patients develop cirrhosis, they stop seeing the endocrinologist and retreat to what they consider the most essential healthcare providers: hepatologists, primary care physicians, the hospital.

What’s worse, as obesity and type 2 diabetes cases continue to flare, physicians may see younger patients with liver disease. Cusi says that he recently saw a 31-year-old man with obesity but not diabetes, with very advanced liver cirrhosis. “The reality is that because two out of three people with obesity and even more with diabetes have fat in the liver, all of them are at risk of developing the inflammation associated with that,” he says.

Steps to Diagnosis

Liver cells never adapted to the accumulation of triglycerides, so when triglycerides sit in hepatocytes, they transform into a more toxic lipid species that cause cells to release cytokines, which leads to inflammation, Cusi tells Endocrine News. “From this very brief path of physiology, we’re going to then know the steps to diagnose it earlier and to treat it, which is to prevent fat from accumulating in the liver cell to start with,” he says.

Cusi goes on to say that endocrinologists should routinely look at liver enzymes and be alarmed when those levels are about 30 IU/ml – not 40 IU/ml – as well as perform a simple diagnostic panel called fibrosis 4 index or FIB-4, which combines age, liver enzymes, and platelets in a formula that can give a rough indicator whether a patient might be at high risk. Endocrinologists can also order or perform in the clinic a simple ultrasound-like imaging study (commonly done in hepatology practices) like transient elastography (FibroscanTM) that measures liver stiffness, a surrogate for liver fibrosis. “It’s better to screen and identify people at a stage of fibrosis when we can prevent irreversible damage” Cusi says.

The first line of treating someone with fatty liver should be a lifestyle intervention, which research shows works, since in individuals with obesity or overweight, the fat is literally sick, since it’s releasing fatty acids and inflammatory cytokines that promote fat accumulation in liver cells, possibly lead to fibrosis and even cirrhosis. For Cusi, reducing overall adiposity in obesity by any means – lifestyle changes, medications, even bariatric surgery – can make the adipose tissue (fat) work like it should again, responding to the body’s insulin so triglycerides stay largely stored within fat cells.

Successful Multidisciplinary Approach

Cusi also points to medications that have shown to be effective in doing just that. Pioglitazone improves insulin sensitivity by normalizing fat metabolism and keeping triglycerides largely stored in adipose tissue. The drug has also been shown to improve dyslipidemia in patients with obesity or diabetes and reduce cardiovascular disease and progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes. “It’s a medication that, because it restores insulin action and overall metabolism, not only improves diabetes but also the mechanisms leading to fatty liver as well, which are closely interconnected,” Cusi says. “Perhaps a combination of these different approaches might be the best moving forward.”

“As endocrinologists, we see these people every day in the clinic. So, if you’ve not diagnosed somebody with steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in the past week, you might’ve missed several patients in a whom you could have started to prevent cirrhosis.” – Kenneth Cusi, MD, chief, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla.

As with most diseases this complex, the best way to succeed is with a multi-disciplinary approach; the endocrinologist should team up with nutritionists and behavioral modification specialists and hepatologists, as well as offer their patients integrated lifestyle programs. And indeed, it will not be as simple as telling the patient to just go lose weight, since obesity is a disease. But fatty liver is not only associated with obesity.

“We know that all patients that have [fatty liver] have insulin resistance, whether they’re lean or obese, and this insulin resistance combines with some other factors in the liver that are probably genetically determined to trigger inflammation and activate pathways that promote liver fibrosis and cirrhosis,” Cusi says. “Our mission as endocrinologists is to identify patients early on.”

Bagley is the senior editor of Endocrine News. In the June issue he wrote about how two community hospitals were successfully implementing Inpatient Diabetes Management Services.

The presentation will be a part of the Clinical Endocrinology Update (CEU) 2021, a comprehensive virtual meeting featuring faculty at the forefront of endocrinology describing the latest advances and critical issues in the field.

Taking place September 10 – 12, each day will feature four hours of live programming, including 36 educational sessions spanning seven topics. All sessions will be recorded and available for viewing 72 hours after they conclude.

Information and registration are available at: endocrine.org/ceu2021.